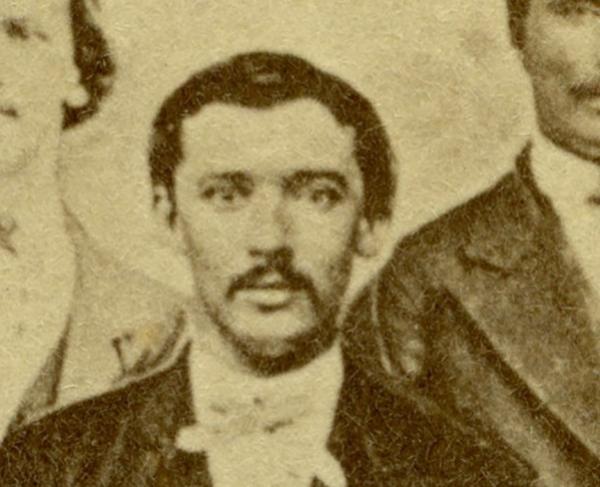

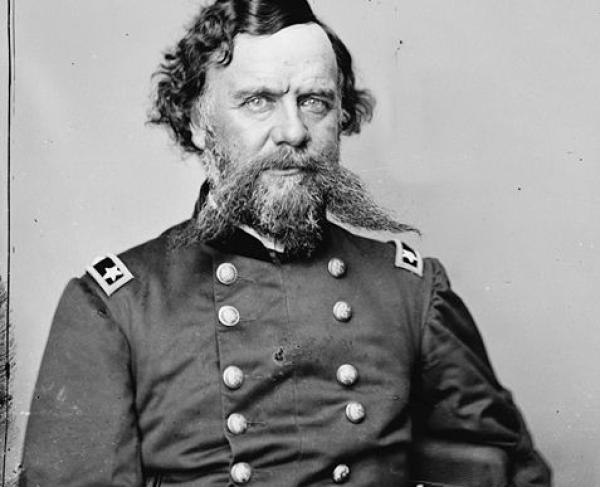

Alpheus S. Williams

On September 20, 1810, Alpheus Starkey Williams was born in Deep River, Connecticut. His father died when he was eight, and his mother when he was 17. Left with a sizable inheritance, the young Williams attended Yale College, graduating in 1831, after which he travelled the United States and Europe. While abroad, he gained a fascination with European military history, touring battlefields, visiting arsenals and museums, and learning about various weaponry.

After this brief sojourn, Williams returned to the states and moved to Detroit, Michigan, in 1836. There, he set up his law practice and married Jane Larned, a widow with whom he had six children. However, like Williams’ parents, she died young, in 1848. Williams remarried in 1875, to a one Martha Tillman.

Williams led an active civilian life in Detroit. In addition to his law practice, he served as judge, bank president, newspaper editor, postmaster, and even unsuccessfully ran for mayor. He also simultaneously began his military career. He enlisted in the local militia, called the Brady Guards, and rose up through the ranks. During the Mexican-American War, Williams served as a lieutenant colonel in the 1st Michigan Infantry, although he and his unit did not see any action in the conflict.

When the Civil War broke out, Williams was appointed brigadier general on May 17, 1861 and was assigned to train Michigan troops as they enlisted. In October, he was ordered to Washington, where he was given a brigade under General Nathaniel Banks.

Williams’ brigade, along with the rest of Banks’ division, pursued Confederate General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, but Jackson quickly outmaneuvered and outfought the Federals. Arriving too late to participate in the Second Battle of Bull Run, he and his troops retreated back to Washington with the rest of the routed federal army.

By September, Williams’ luck seemed to change, as he was now at the head of a division, and troops under his command found General Robert E. Lee’s famous “Lost Order Number 191” that revealed his plans for the 1862 Maryland Campaign and gave Union commanders an advantage. At the following Battle of Antietam, Williams was temporarily corps commander after the death of XII Corps Commander Joseph Mansfield. He held an advanced position against the Confederate left flank – once again facing off against Jackson from the East Woods near the Cornfield. Some of the XII Corps units created a lodgment in Jackson’s line near the Dunker Church and in the West Woods. However, in doing so, Williams lost a quarter of his men in casualties.

At the 1863 Battle of Chancellorsville, Williams was back at the head of his old division, when Jackson’s corps flanked and smashed the right flank of the Union Army of the Potomac, Williams’ division held the right center of the Union line. Williams’s men dug in and were able to stop Jackson’s men from overrunning the entire Union Army. This stand was courageous but costly; the division suffered 1,500 casualties, including the wounding of Williams’ favorite horse “Old Plug Ugly.”

In the Battle of Gettysburg, Williams’ division, and the rest of the XII corps, occupied the Culp’s Hill sector on July 2. Due to a confusing Union chain-of-command, Williams found himself once again as the temporary commander of the XII corps. Later that day, due to a massive attack on the Union left, commanding General George G. Meade ordered Williams to transfer his entire corps to reinforce the left side of the line. Williams convinced Meade of the strategic importance of Culp’s Hill; Meade agreed to leaving one brigade there. This brigade held out against General Edward Johnson’s division through the night, until the rest of Williams’ corps returned. Early the next day, Williams launched an attack that drove back the Confederates, and the sector fell into a stalemate throughout most of July 3.

In September, following the Union disaster at the Battle of Chickamauga, Williams’ division was among the eastern units to be sent west to relieve the besieged federal troops in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Williams’ division never reached Chattanooga, having been assigned to guard railroads in eastern Tennessee.

By early 1864, Williams’ division was attached to the XX Corps, Army of the Cumberland, and served in General William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. They fought with distinction in the preceding battles, particularly at the Battle of Resaca. Williams himself was wounded at the Battle of New Hope Church. After the fall of Atlanta, the division took part in Sherman’s March to the Sea as well as the Carolinas campaign. Williams briefly led the XX corps and was promoted to Brevet Major General on January 12, 1865.

Despite a mixed record, Williams came to be beloved by his men; they affectionately referred to him as “Pap” Williams. He treated them like they were his own sons and was said to have felt sorrow over each individual casualty. Unfortunately, Williams was not nearly as loved by the high command of the Union Army. He was often passed over for praise and promotion, which can likely be attributed to the fact that he was not a career soldier from West Point, unfamiliarity of the high command due to his time in the Shenandoah Valley, and his inability to promote himself via journalists.

After the Confederate surrender at Bennett Place, Williams served as a military administrator in southern Arkansas until 1866. He then returned to Michigan and civilian life. Financial hardships forced him to accept a post as the US Minister at San Salvador (modern El Salvador) until 1869. He unsuccessfully ran for governor of Michigan, but then successfully ran for Congress twice, in 1874 and 1876. It was during his second term as Representative of the 1st Michigan district, when Williams suffered a stroke on December 21, 1878, and died four days later in the Capitol building. He is buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.