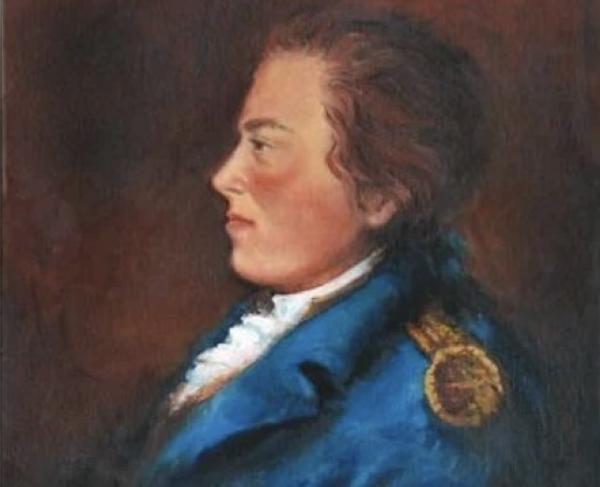

Andrew Oliver

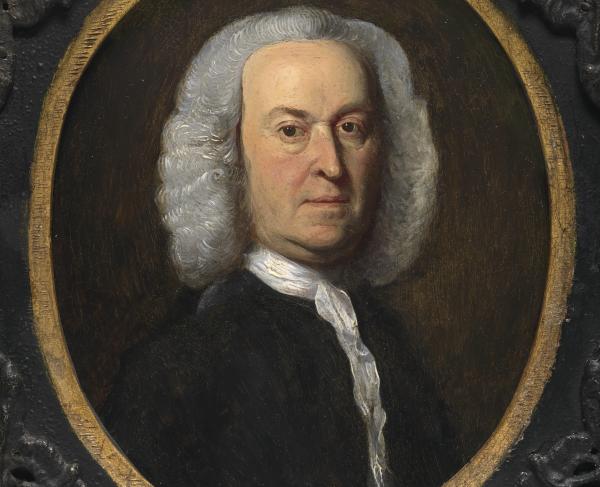

Born in 1706, Andrew Oliver grew up among an affluent Boston family. His father, Daniel Oliver, made his fortune as a prosperous and politically active merchant, while his uncle Jonathan Belcher served as governor of Massachusetts for more than a decade. As a result of his family’s connections, Oliver attended Harvard College at a young age. After he graduated in 1724, he and his brother Peter followed in their father’s footsteps by establishing a business along Boston’s Long Wharf. The venture grew so lucrative that the brothers eventually controlled much of the commerce along the wharf.

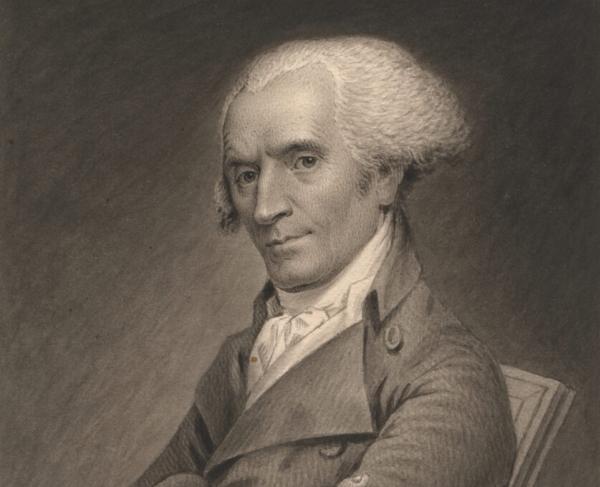

In 1728, Oliver married Mary Fitch, the daughter of a British officer. The two of them had three children (only one of which survived to adulthood), but Mary died in 1732, leaving Oliver a widower. After spending two years in England, he remarried in 1734—this time to Mary Sanford, the sister-in-law of future Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson. Together, Oliver and Sanford had fourteen children.

With strong connections to both the mercantile and civic life of Massachusetts, Oliver eventually decided to enter politics. He first won election as Boston’s town auditor but served in numerous other positions throughout his career, including as the provincial secretary and a delegate to the provincial assembly. As Oliver’s political influence grew, he assumed leadership of the Hutchinson-Oliver faction which dominated Massachusetts politics prior to the American Revolution.

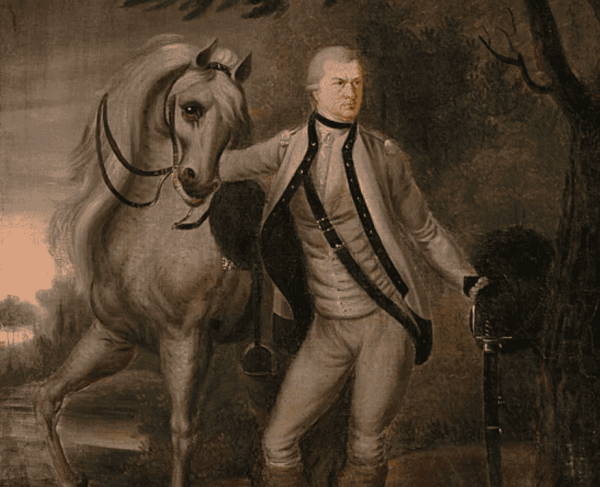

In 1765, Oliver reluctantly accepted the post of stamp commissioner. In that position, he administered Parliament’s unpopular Stamp Act. Though Oliver privately opposed the legislation, he publicly supported it—to the chagrin of many American colonists. Protestors hanged Oliver in effigy from the Liberty Tree near Boston Common on August 14, 1765. Later that evening, an angry crowd tore down the effigy and paraded it around the city in a mock funeral procession. When the crowd arrived at Oliver’s office, they looted it and then marched to his house where they beheaded and burned the effigy. Though Oliver remained unharmed, he returned to his home to find it ransacked.

In light of the chaos, Andrew Oliver resigned the following day. However, the disgruntled colonists insisted he publicly rescind his office under the Liberty Tree only after he was shamefully paraded through the streets by protestors. Oliver’s resignation as stamp collector sparked turmoil across the thirteen colonies and inspired the formation of resistance groups like the Sons of Liberty.

Despite his disrepute, Oliver assumed the position of lieutenant governor of Massachusetts in 1771 when Thomas Hutchinson became governor. But Oliver’s reputation continued to suffer when correspondence between he and Hutchinson fell into the hands of a Boston newspaper. The press published the letters and characterized them as proof that Hutchinson and and his lieutenant governor called for the curtailment of colonial rights. The Hutchinson Letters Affair, as it became known, outraged men and women across the American colonies, further damaging Oliver’s stature. His health began to decline, particularly after the death of his wife in 1773, and Andrew Oliver died on March 3, 1774. Members of the Sons of Liberty celebrated his death, while other political opponents of his protested his burial. His son and namesake grew to be a prominent American scientist and controversial figure in the American Revolution.