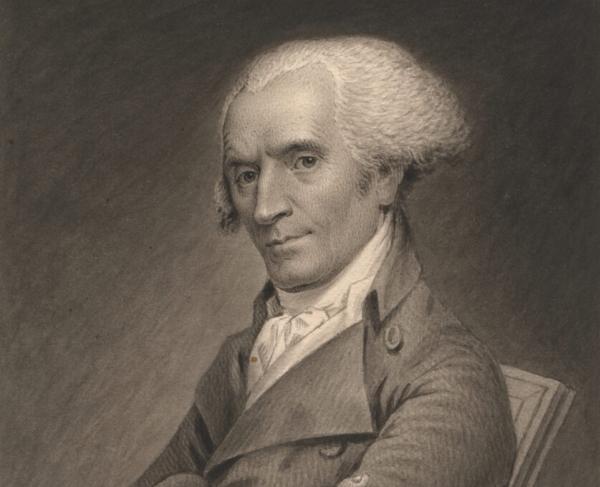

Benjamin Rush

Like many of the great men of the Revolution, Benjamin Rush was a multi-faceted man: a politician, physician, humanitarian, educator, and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Following revolutionary ideals in all aspects of his life, Benjamin Rush made his mark in history with his innovative medical texts and ideals, and sometimes controversial views.

Benjamin Rush was born on December 24, 1745, in Byberry, Pennsylvania, outside of Philadelphia to John Rush and Susanna Hall, the fourth of seven children. His father died when he was just six years old. While his mother did the best to take care of her family, young Benjamin was placed under the care of his uncle, Reverend Samuel Finley, to receive a formal education at the West Nottingham Academy. In 1760, Rush graduated from the College of New Jersey [now Princeton University] with a degree at just fourteen years old. To become a physician, he entered an apprenticeship with Dr. John Redman to expand his medical knowledge in addition to attending lectures by other prominent Philadelphian physicians including Dr. William Shippen Jr. and Dr. John Morgan at the College of Philadelphia. However, instead of attending the newly established medical school at the College of Philadelphia, in 1766, he sailed to Scotland to attend the University of Edinburg to attend the more renowned medical school that had been established since 1726.

He completed his medical training in 1768 and went to London to practice at St. Thomas Hospital. There, he became friends with Benjamin Franklin and through this connection, he acquired a position as a Professor of Chemistry at the College of Philadelphia. When back in the Colonies, he became a prolific writer, writing many volumes of medical texts, patriotic essays, and even the first book of chemistry in America titled A Syllabus of a Course of Lectures on Chemistry. While he was focused primarily on his medical career, he was not blind to what was happening in the colonies and often followed modern politics which helped shape his political and medical career.

Following his Enlightenment and republican beliefs of equality, education, and liberty, he became very active in several organizations prior to the Revolution. He joined the American Philosophical Society and became a leading member, helped to organize the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and published sermons and articles about temperance, exercise, politics, and the issues of owning slaves. Through these endeavors, he became a regular correspondent with several prominent revolutionaries including Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, and John Adams.

When revolution came in the 1770s, Benjamin Rush did not shy away from the chance to get involved. He became a member of the Sons of Liberty, represented Pennsylvania in the Continental Congress, and signed the Declaration of Independence. He also served the revolutionary cause with his medical knowledge. Not only was Rush out in the field treating wounded and sick soldiers during the Philadelphia Campaign in 1777, but he also became the Surgeon General of the Middle Department of the Continental Army. In this role Rush oversaw all medical aspects of the army in the states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland. Rush found the army experiencing high rates of disease, inadequate supplies, and poor direction under its current chief physician & director general overseeing the entire Continental Army, Dr. William Shippen Jr. In 1777, he published Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers, Addressed to the Officers of the Army of the United States in which he argued that, “the art of preserving the health of a soldier consists of attending to the following particulars: 1. Dress. 2. Diet. 3. Cleanliness. 4. Encampments. And, 5. Exercise.” These directions and many of his other medical texts were republished throughout the American Revolution and well into the 20th century as one of the leading texts of preventative medicine. However, despite his innovative methods and revolutionary ideals, he was by no means a quiet man, ultimately creating controversy when he spoke his mind.

Rush blamed the poor state of the continental army on Dr. William Shippen Jr., who Rush believed was misusing supplies and under-reporting deaths. He wrote his complaints to General George Washington, who in turn passed the letter to Congress, but Shippen ultimately stayed in his position until 1781. When his suspicions were not acted upon, Rush turned is complaints on General Washington writing two anonymous letters questioning Washington’s command. One letter in 1778 was sent to Patrick Henry, another sent to John Adams. Patrick Henry’s letter made it into Washington’s hands where his handwriting was recognized and the resulting scandal resulted in Benjamin’s resignation from the army, forcing him to return to his private practice in 1778.

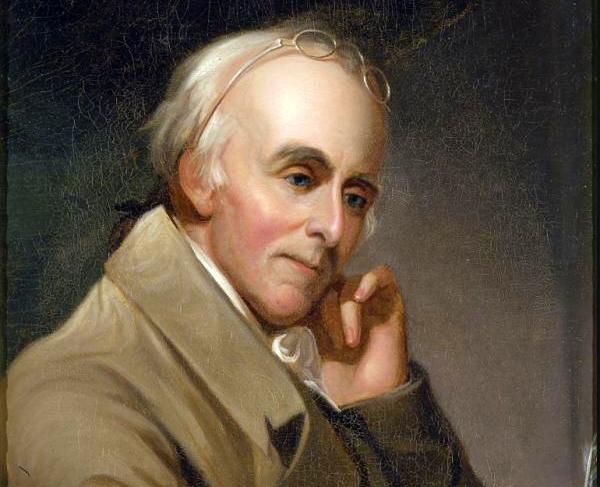

The return to civilian life allowed Rush to again concentrate on his medical career. He became a member of staff at the Pennsylvania Hospital focusing on the care of the poor, social reform, and the humane treatment of mentally ill patients, even opening America’s first free dispensary (pharmacy) in 1786. Yet, while he was innovative in this aspect of his medical career, he was also a fervent advocate of “heroic” medicine, which claimed that bleeding and purging were some of the best treatments for any ailment. He wrote about it extensively in his 1789 “Medical Inquires and Observations” and tested his theory during a Yellow Fever epidemic in 1793, but he did not keep detailed records of his own cases and so the method was quickly questioned by fellow physicians and fell out of favor by the early 1800s. By the turn of the century, he shifted his focus from diseases to mental illness, being one of the first to delve into the study of psychiatry with his last publication “Medical Inquiries and Observations upon the Diseases of the Mind”.

Throughout his life, Benjamin Rush was an outspoken man on a variety of topics ranging from social reform, slavery, temperance, the Constitution, independence, and more. While some of his beliefs proved to be controversial, such as his views on Washington to the evils of slavery (despite owning a slave himself), when Benjamin Rush died on April 19, 1813, he was hailed as one of the greatest doctors of his time and the “father of American psychiatry”.

Further Reading:

- Benjamin Rush: Patriot and Physician by Alyn Brodsky

- Rush: Revolution, Madness, and the Visionary Doctor who Became a Founding Father by Stephen Fried

- The Selected Writings of Benjamin Rush by Dagobert D. Runes

- Dr. Benjamin Rush: The Founding Father who Healed a Wounded Nation by Harlow Giles Unger