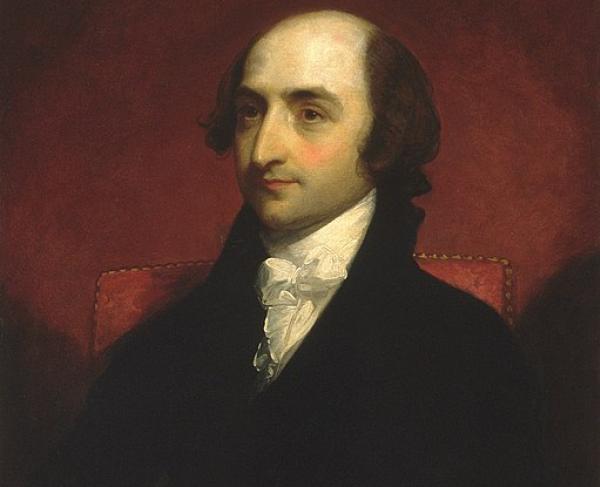

Bradley T. Johnson

The man who perhaps did the most to promote Maryland’s involvement in the Confederate cause, despite the state remaining in the Union, Bradley Tyler Johnson was born in Frederick, Maryland, on September 29, 1829. The Johnsons were a prominent family in Frederick, and the young Bradley seemed poised to follow in their footsteps. He attended Princeton College, graduating in 1849, and immediately after attending Harvard Law School. After graduating, he was admitted to the North Carolina Bar. In North Carolina, he met his future wife, Jane Claudia Saunders, who was part of another politically prominent family.

Upon returning to Maryland, he served as the state’s attorney for Frederick County. In 1859, he was chair of the Maryland Democratic Committee, and the next year, served as a delegate to the contentious Democratic National Convention. He was among the Southern delegates who walked out of the convention to nominate John C. Breckinridge, a defender of the South, slavery, and states’ rights.

So when Abraham Lincoln, a Republican and anathema to everything Johnson stood for, was elected to the presidency, he was predictably angry and rallied to the cause of the seceding states. He thought Maryland would join them, but federal interference was forcing her to remain in the Union. To Johnson, the Pratt Street Riot, in which the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment and a pro-Southern mob clashed, resulting in the deaths of both soldier and civilian, and the subsequent Federal occupation of the city was evidence of this. The election of the Unionist August Bradford to the governorship further convinced him of a conspiracy to hold Maryland hostage to the Union. “Maryland…suffered the crucifixion of the soul, for her heart was with the Confederacy, and her body bound and manacled to the Union,” Johnson wrote.

Johnson took matters into his own hands. In early 1861, he set to work organizing a company of pro-Southern militia in Frederick. He was summoned to Baltimore in the wake of the riot by the Southern sympathizing commander of the police force, but the city had calmed down by the time they arrived. Johnson’s men returned to Frederick, where they were tasked with protecting pro-Southern state legislators when the legislature convened in that city in late April. Although some feared they would vote to secede, the Maryland legislators chose to remain in the state.

As a result, on May 9, Johnson and his men left Frederick and Unionist Maryland, crossing the Potomac River to Confederate Virginia. His unit was incorporated into General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s brigade, the famed Stonewall Brigade Ferry. Throughout the war, Johnson and his men would agitate for a separate Maryland detachment, called the Maryland Line, that would come to fruition in 1863. But for now, Johnson’s men from Frederick and other renegade Marylanders formed the First Maryland.

The First Maryland first saw action at First Bull Run, where they helped rout the Federal Army. In the inactive months afterward, however, the men of the First Maryland became increasingly discontented, with enlistments expiring. Sorely disappointed and with a near mutiny on his hands, Johnson eloquently admonished them, which had the effect of transforming them into dedicated, loyal soldiers. They participated in Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, where at the Battle of Front Royal, they fought against their fellow Marylanders in the 1st Maryland USA. After, they successfully served in the Seven Days’ Battles in central Virginia. The First Maryland was finally mustered out in August 1862, though many Maryland veterans would go on to serve in other units.

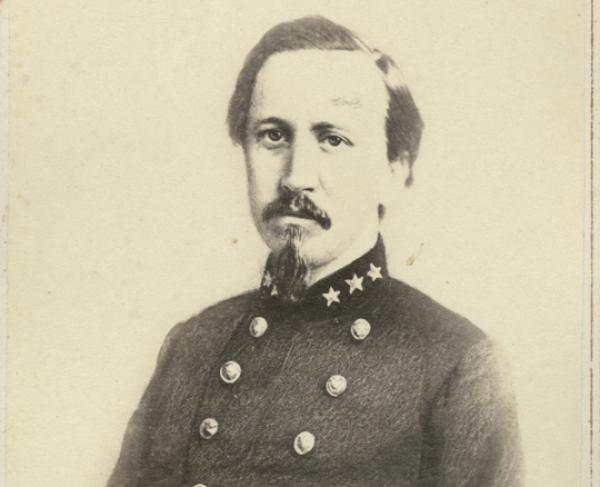

Johnson led a brigade at Second Bull Run, where his service prompted praise from Jackson himself. Johnson, however, did not participate in Maryland’s most famous battle, Antietam. Instead, he had gone to Richmond to petition for the Maryland Line, but he ended up serving on a military court there because of his prior legal experience. In the spring of 1863, Johnson’s dream finally came true; the Maryland Line included an infantry regiment, a cavalry unit, and an artillery outfit, all of them made up of Marylanders. Johnson then was promoted to brigadier general of these Maryland men.

In 1864, Johnson conceived of a plan to kidnap Lincoln while he was at the Soldiers’ Home near the outskirts of Washington, DC. However, this plan was thwarted when he was called to participate in General Jubal Early’s raid on Washington. He and his men secured the Confederate flank in the Battle of Monocacy, just outside Johnson’s hometown of Frederick. He and the First Maryland Cavalry were sent to free Confederate prisoners at Point Lookout, Maryland. On their way, they burned Governor Bradford’s house in retaliation for the governor of Virginia’s house being burned by Union forces. They were within eighty miles of the prison when they were called back when Federal men were able to reinforce Washington.

Afterward, Johnson was part of the contingent sent to raid southern Pennsylvania. They arrived at Chambersburg in late July and demanded a ransom of $500,000 in greenbacks (U.S. currency) or $100,000 in gold. The town was unable to come up with the amount, and so the commanding general, John McCausland, ordered the town burned. Johnson didn’t fully support this action, leading to conflict with his superior. Soon after, a similar incident occurred at the town of Hancock, when it escalated into an argument.

On August 7, the Maryland Line was surprised by Federal forces, many of them captured. Johnson was blamed for this debacle, which was the end of the Maryland Line. Without any command, he was sent to Salisbury, North Carolina, where he commanded the Confederate prison until May 1, 1865, when he surrendered to Union forces.

After the war, he settled in Richmond and practiced law. He became involved in politics, elected to the Virginia State Senate in 1875, and was initially a supporter of rights for Black Americans, with “Johnson Clubs” being political organizations of African Americans. However, Johnson soon lost their support as he became increasingly involved with the Lost Cause. He returned to Maryland in 1879, but returned to Virginia after the death of his wife, where he died in 1903.