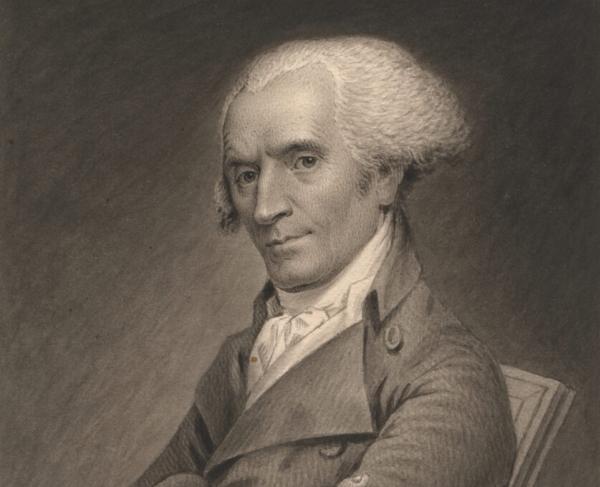

Casimir Pulaski

Growing up as a privileged aristocrat, and with a reputation of more bravado than sense, Casimir Pulaski nonetheless made a significant impact on the course of the Revolutionary War with a reckless courage and a set of skills rarely found in his American counterparts.

Casimir Pulaski was born on March 4 or 6, 1745, in the city of Warsaw, then the capital of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the most politically odd states in Europe at the time. Today we would describe its government as a constitutional monarchy, similar to Great Britain, but the similarities only went so far. In Poland-Lithuania, the king was elected to the throne rather than inheriting it from his predecessor, and his powers were heavily curtailed by the men who did the electing: the Sejm, or Parliament. Members of the Sejm were made up entirely from the nobility, but they numbered enough to make the system almost quasi-democratic. Furthermore, within Polish borders lived significant populations of Protestant and Orthodox Christians, as well as one of the largest Jewish minorities in Europe, in contrast to the Catholic majority, which lead to the Commonwealth adopting a policy of religious toleration almost unheard of in its day. Ironically, it was these traditions of political liberty as well as his own Enlightenment education that forced the young Pulaski from his home.

Poland in the 18th century was not the formidable power it had once been, and now faced heavy pressure from neighboring Russia to act as its protectorate. In 1768, however, a group of nobles and patriots, including Pulaski, formed the Confederation of the Bar and declared a rebellion against the government to remove the overbearing Russian influence. Pulaski first made a name for himself during this war, for a string of small but unlikely victories against Russian forces. Like most Polish military men of his class, he was a cavalryman, and by all accounts a skilled rider and swordsman. Unfortunately, Pulaski also participated in a failed attempt to kidnap the pro-Russian King Stanislaw II Augustus, which ended the Confederation’s foreign support from France and Austria, leading to its defeat in 1772 and the First Partition of Polish territories between Austria, Prussia and Russia. Facing defeat and charges of attempted regicide, Pulaski fled Poland to Prussia, then the Ottoman Empire, and then finally France. The French army refused to allow an accused regicide to join their ranks and the count might have died in a debtor’s prison or been surrendered to Russia had the American Revolution not provided him with an opportunity.

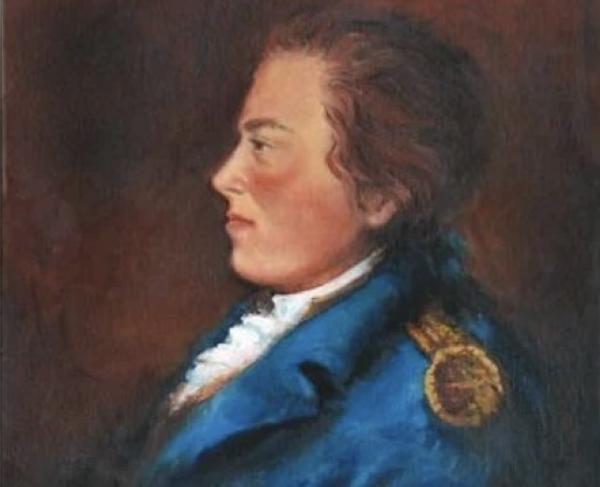

When Pulaski first met Dr. Benjamin Franklin, the American commissioner to France, in the spring of 1777, the printer-turned-diplomat was already aware of the count’s previous exploits. This was good news for Pulaski, as Franklin and other Americans had been bombarded with hundreds of requests from European military careerists for a commission in the Continental Army, and Pulaski’s apparent talent and zeal for liberty placed him well ahead of the other candidates. Many French officials also encouraged Franklin to send Pulaski to America, if only to remove a potential agitator. They even offered to pay for the voyage, as Pulaski had no money to do so on his own. Pulaski embarked from France on the 13th of June and landed in Boston forty days later, learning as much English as he could along the way. Eager to get right into the thick of the fighting, he traveled to the encampment of General George Washington, who gently informed the aristocrat he needed the approval of Continental Congress before joining. Undeterred, Pulaski refused to wait for official approval before jumping into one of the most important battles of the war at a critical moment: The Battle of Brandywine. As the British forced the Americans off the field on the 11th of September, Washington realized, to his horror, that the right flank of his army was about to collapse, potentially causing a general rout and destroying his army. In a flash, Pulaski volunteered to countercharge the British and give the Continentals time to withdraw in good order. With no time to argue, Washington entrusted Pulaski with his own mounted guard, about thirty in number, and watched as the Polish volunteer led his band directly into the fray, delaying the British long enough for the Continentals to retreat and possibly saving Washington’s life. For this gallant deed, Congress immediately commissioned him as a Brigadier General, with the honorific “Commander of the Horse.” He also took part in the Battle of Germantown the following month.

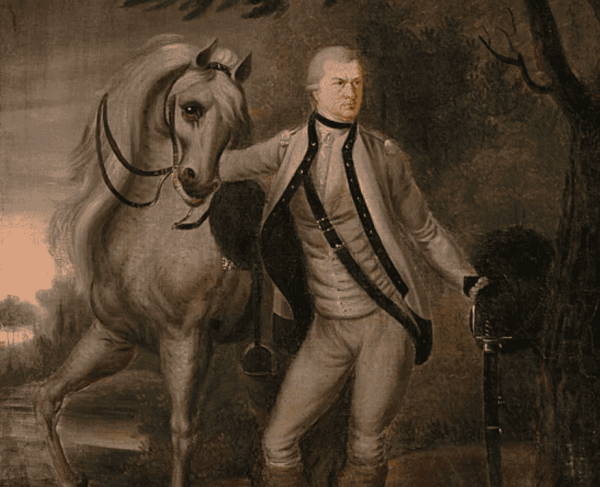

Pulaski spent most of his generalship leading small bands of horsemen on scouting patrols are raiding parties, as the Continental Army did not generally have a cavalry arm to speak of when he arrived. To him though, such a situation was unacceptable, and began working to rectify the issue. In the early spring of 1778, he offered to raise an independent cavalry unit for the army and was allowed to do so with little supervision or collaboration with his American counterparts, mostly because they hated working with him and dealing with his vain, arrogant demeanor. Taking mostly recruits from the area around Baltimore, Maryland, Pulaski presented his Cavalry Legion, equipped and armed as lancers and dragoons in the style of his home country and trained to those standards, on the 28th of March. Many Continental Army officers spoke highly of the unit’s fighting ability, but Pulaski finally ran afoul of Washington’s good will when he began requisitioning supplies and steeds from locals he suspected of Loyalist sympathies, customary in Europe but anathema to the Revolution’s ideological aims. In 1779, Washington sent Pulaski south to Charleston, where he was ordered to support General Benjamin Lincoln in his march to recover Savannah, Georgia from British occupation. Unfortunately, Pulaski’s characteristic recklessness tended to get the better of him in South Carolina more often than not. On the 11th of May 1779, he charged a British raiding party led by Brigadier General Augustine Prevost outside of Charleston that cost his men dearly. Months later, on the last day of the Siege of Savannah, Pulaski attempted to rally a group of fleeing Frenchmen by charging a British position, similar to his actions at Brandywine, but was sadly struck by grapeshot and died some days later. He was buried with full honors at an unknown location, and his Legion was incorporated into the rest of the Continental Army.

Casimir Pulaski was not the noted thinker fellow Polish volunteer Thaddeus Kosciuszko was, and he was greatly disliked by his contemporaries. After the war, however, he became an important symbol of both American and Polish independence for his battlefield valor in both Europe and North America, as well as his later sacrifice. In 2009, the United States Senate granted him the posthumous reward of honorary United States citizenship, one of only eight individuals to ever be granted such an honor. In military history, he is known to this day as “The Father of the American Cavalry.”