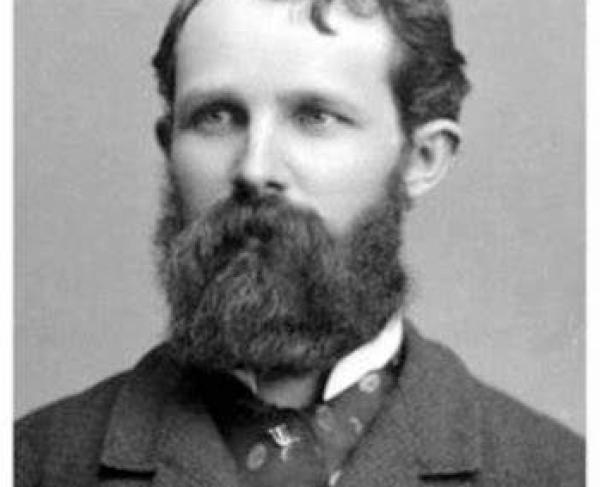

Chang and Eng Bunker

The origins of the phrase “Siamese Twins,” Chang and Eng Bunker were conjoined twins who operated a plantation in North Carolina during the Civil War.

Born on May 11, 1811, in Mekong, Siam, modern-day Thailand, Chang and Eng were connected at the breastbone by a small piece of cartilage. The twins walked side by side and had completely separate organs aside from their fused liver. After meeting British merchant Robert Hunter in 1824, the twins and their mother recognized the financial potential of exhibiting Chang and Eng. Beginning in 1829, Chang and Eng embarked on a series of tours in Boston, London, and New York City.

The Bunker Twins became naturalized citizens of the United States in the 1830s and resided in North Carolina. On March 1, 1845, the twins purchased 650 acres in Surry County, North Carolina, and started their family-owned plantation. Chang and Eng invested $10,000 in property and $60,000 in the importation of goods, which holds an estimated value of $1.8 million in modern times. The twins constructed two homes, Mount Airy and Traphill, for their respective wives and children. Chang and Eng purchased 18 slaves to maintain the property and take care of their families. Their slave-owner status cemented their support for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

In October 1860, Chang and Eng signed with P.T. Barnum and agreed to have a wax sculpture of themselves on display in Barnum’s American Museum in New York City. Chang and Eng remained in business with P.T. Barnum until the onset of the Civil War in 1861.

During the Civil War, Chang and Eng’s conjoined bodies became symbols for the divided American nation. The Louisville Journal suggested that the Bunker Twins symbolized the rivaling factions within the Democratic Party. The New-York Tribune falsely reported that Chang and Eng disputed over secession, thus reflecting the tensions of the American nation regarding the issue of slavery. However, the Bunker twins were unable to directly participate in the Civil War. Eng was drafted to the Union Army in 1865, despite his political affiliation to the Confederacy. Eng’s conjoinment to Chang prevented him from enlisting in the army.

While Chang and Eng were unable to serve in the Civil War, their sons fought for the Confederacy. Christopher Bunker, the son of Chang, enlisted in the Thirty-seventh Battalion of the Virginia Cavalry on April 1, 1863. During Confederate Brigadier General John McCausland’s attack on Chambersburg, Christopher Bunker was one of 2,600 men recruited for the offensive campaign. Though the Confederates succeeded in burning Chambersburg, Union officers imprisoned Bunker, along with other members of his Battalion, while they camped out in Moorefield, West Virginia. Christopher Bunker was a prisoner at Camp Chase, the largest Federal military prison at the time, and remained there until April 17, 1865.

Stephen Bunker, the son of Eng, also enlisted in the Thirty-seventh Battalion of the Virginia Cavalry in 1864. Stephen Bunker successfully escaped the conflict at Moorefield, unlike his cousin. While fighting near Winchester in September 1864, Stephen Bunker was severely wounded. Bunker finished out the battle while wounded, and remained active in military service until the Civil War’s end. After the war, both Christopher and Stephen Bunker moved home to the Mount Airy plantation.

After the Civil War, Chang and Eng Bunker struggled financially, as the majority of their investments went to the Confederate cause. Additionally, Chang and Eng were now unable to rely on slave labor and as a result, their plantation diminished in its profitability. These financial hardships promoted Chang and Eng to rejoin P.T. Barnum’s traveling circus.

Despite consulting numerous doctors over the course of their lives, Chang and Eng were unable to undergo a separative surgery. Chang Bunker died on January 17, 1874, from a cerebral blood clot, and Eng Bunker died three hours later.