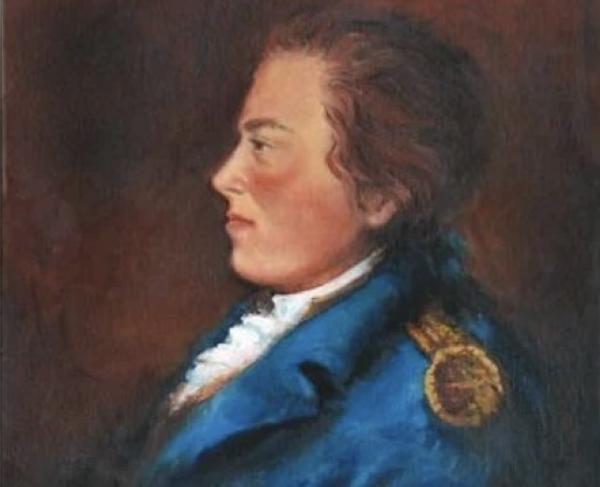

Charles Gravier

Despite not being American, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, was one of the most important figures in securing American independence. He was born on December 20, 1719, in the French province of Dijon.

He accompanied his uncle the Chevignard de Chavigny on diplomatic missions to Lisbon, Portugal, and Frankfort, (modern-day Germany), which were the beginnings of Gravier’s long career in diplomacy. He represented France at Trier, a German principality in 1750. He then served as ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul in 1754, where he defended French policies to the Turks, who were hostile to France’s allies the Austrians. In 1771, he became ambassador to Sweden, where he helped King Gustav III defend against a coup d’etat.

In 1774, when King Louis XVI ascended to the throne, Gravier was recalled to France to become minister of foreign affairs. At this time, Gravier had spent almost all of his adult life outside of France, which gave him a broader perspective of international affairs. He worked on maintaining friendly relations with Austria and protecting the Ottoman Empire. He also wanted to reduce English power, which had exponentially grown after their victory in the Seven Years War. France’s defeat in the same war had left many Frenchmen with a desire for revenge and a chance to reassert France’s position as the preeminent European power.

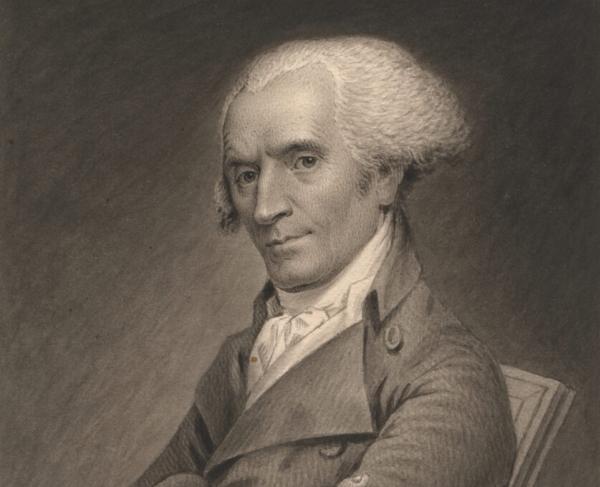

He was given a chance to strike at British power when the American War for Independence broke out in 1775 and the colonies declared independence the next year. However, he was fearful that if France fully committed to the Americans’ cause too early, the British would easily defeat their rebellious colonists and then punish the French for daring to support them. American military failures, such as the loss of Long Island, did not bode well. Gravier and the French government needed to proceed with caution until the Americans had demonstrated their ability to resist Britain and their commitment to independence. Gravier also needed time for the French army and navy to regain strength (as both were still rebuilding after the Seven Years War) and for Spain to agree to support the rebels as well. Spain was hesitant because they feared setting a dangerous precedent for their own colonies. In the meantime, Gravier decided to clandestinely aid the Americans, first in the form of money, then in arms, ammunition, supplies, and volunteers.

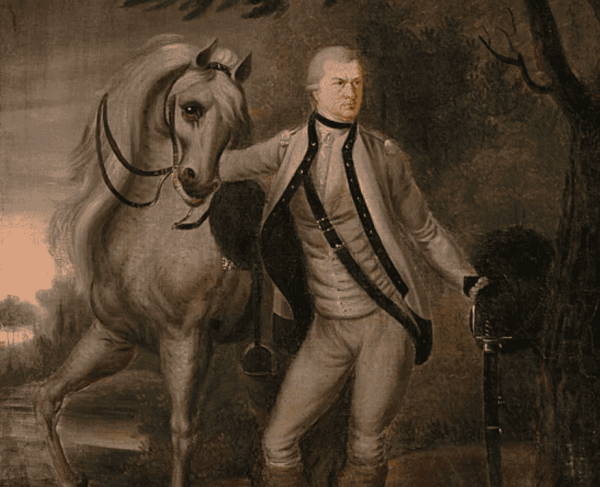

The Americans convinced France of their seriousness and military skill at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, where American forces routed and captured a large portion of British General John Burgoyne’s army. This event, as well as Benjamin Franklin’s insistent diplomacy, was what Gravier needed to officially support the Americans. He convinced Louis XVI and the Spanish government to enter into a formal alliance with the former colonies, thereby recognizing them as an independent state.

French aid tipped the balance of the war. Their presence was most impactful at the Siege of Yorktown, with the French navy cutting off the British army from the sea. When General Sir Charles Cornwallis surrendered soon after, the war was effectively over.

At the peace of Paris, Gravier did not try to regain French territory lost in the Seven Years War but helped the colonists get liberal terms from their former mother country. Despite the Americans’ success, intervening in the conflict would have serious ramifications on France itself. The large debt accumulated would accelerate the coming of the French Revolution.

Gravier died on February 13, 1797, in the midst of negotiating a commercial treaty with his former enemy Great Britain.