Daniel E. Sickles

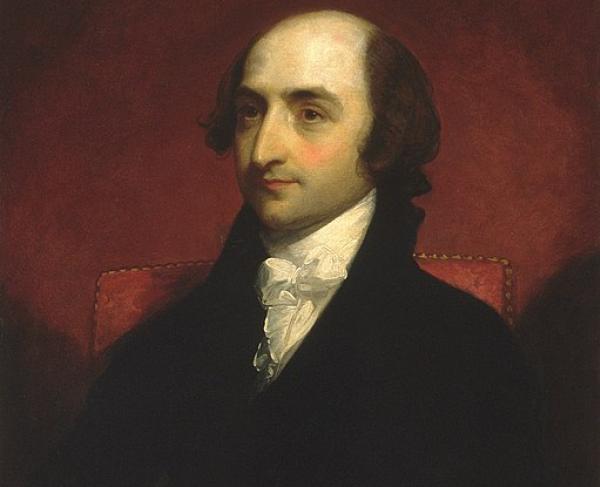

Few figures of the American Civil War are more dubious than Daniel Edgar Sickles. His self-motivated actions on and off the battlefield have been debated by historians and buffs to this day. Even his date of birth elicits controversy. Daniel Sickles was supposedly born in New York City on October 20, 1819—although it is quite possible he was born on October 20, 1825.

A product of the "Tammany Hall" political machine, Dan Sickles served as both a lawyer and politician in the Empire State. At the age of 28, his political connections gained him the position of corporation counsel of New York City, and also led him to a New York State Senate seat.

In 1856, Sickles was elected to the United States House of Representatives. Dan Sickles and his young wife, Teresa Bagioli Sickles, lived a lavish Washington D.C.. lifestyle. The two leased a mansion at Lafayette Square, just across from the White House. The couple hosted grand dinner parties for the upper crust of Washington society. It was well-known within the Washington social circles that the couple were less than faithful in the marital vows.

On February 25, 1859, Sickles shot and killed his wife's lover, Philip Barton Key—in broad daylight. The victim was the son of Francis Scott Key, (author of the Star Spangled Banner). Future Secretary of War Edwin Stanton represented Sickles in what would be the first successful use of the "temporary insanity" defense in the United States. While the murder and acquittal were both shocking, the true shock to the Washington elite came when Sickles did not divorce his wife. Few socialized with the couple. One diarist noted that Sickles was "left alone as if he had the smallpox."

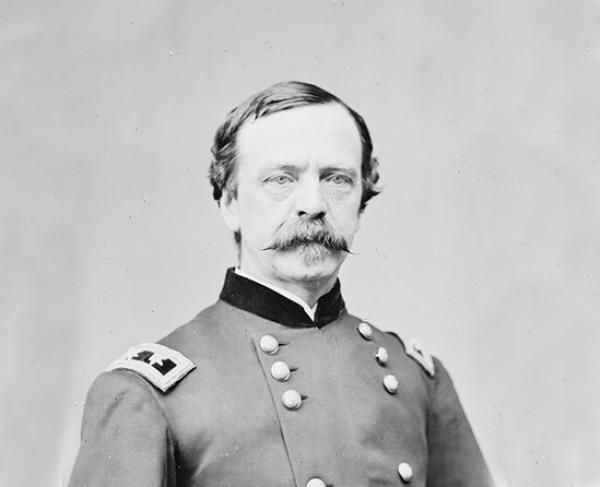

Sickles began his military career serving as Colonel for the 70th New York Infantry before being appointed brigadier general of volunteers, commanding New York's Excelsior Brigade. In November 1862 he was promoted to major general. While he was extremely brave in battle, he often found himself in conflict with superior officers.

Sickles served in Joseph Hooker's Division of the Third Corps during the Peninsula Campaign and returned to New York for recruiting duties for much of the late summer and early fall of 1862. He commanded a division at Fredericksburg, and then assumed command of the Third Corps prior to the Chancellorsville campaign.

At Chancellorsville, Sickles received permission to reconnoiter the Confederate lines, as word spread of a possible Confederate movement in Federals front. Sickles corps engaged the Confederates near the Catharine Iron Furnace. Joseph Hooker, now in command of the Army of the Potomac, convinced himself that Sickles had stumbled upon a retreating Confederate column. Rather than pull Sickles back to the main Union battle line, Hooker left Sickles 18,000 man corps nearly one-and-a-half miles from the closest Federal support. Later that same afternoon, General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's men, which they had mistakenly believed to be in retreat, attacked the Federal right flank. With Sickles men in advance of the main Union lines, a gap was unwittingly created by Hooker, between his men on the right flank and the rest of the Union Army. Sickles attempted to fight his way back to friendly lines. Darkness and the close choking woods prevented him from doing so, but Sickles was able to secure a key piece of high ground—Hazel Grove.

The next morning, May 3, 1863, Sickles was ordered to give up Hazel Grove by Joseph Hooker. Sickles protested to no avail. Confederates quickly seized the high ground and pummeled the Union center. By 10 AM the Federals were withdrawing to a new position.

While Sickles had somewhat stretched his orders during Chancellorsville, he outright disobeyed direct orders from Maj. Gen. George G. Meade during the Battle of Gettysburg. Sickles orders were to cover the Round Tops on the Union left flank, instead he moved his men to the Peach Orchard. The result was that the Third Corps was overrun and driven from the field. Sickles lost his right leg in the disaster. Despite this fiasco Sickles was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions at Gettysburg. The citation states that he, "displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded."

After the surgery, Sickles gained lasting fame for donating his amputated limb to the Army Medical Museum in Washington, DC. The limb was received with a small card which said, "With the Compliments of Major General D.E.S." Part of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, the Army Medical Museum has kept Sickles' amputated limb on display.

Abraham Lincoln sent Sickles to the South where he assessed the effects of slavery on African Americans and gave suggestions for Reconstruction in the future. After the war he held a variety of positions: diplomat to Colombia, Military Governor of South Carolina, Minister to Spain, Chairman of the New York Civil Service Commission, New York City Sheriff, New York Congressman and Chairman of the New York State Monuments Commission. He was removed from the monuments committee in 1912 for allegedly pocketing funds. Despite this, he was instrumental in establishing the Gettysburg National Battlefield Park. He visited Gettysburg many times after the war.

Sickles died of "cerebral hemorrhage" at New York City on May 3, 1914. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.