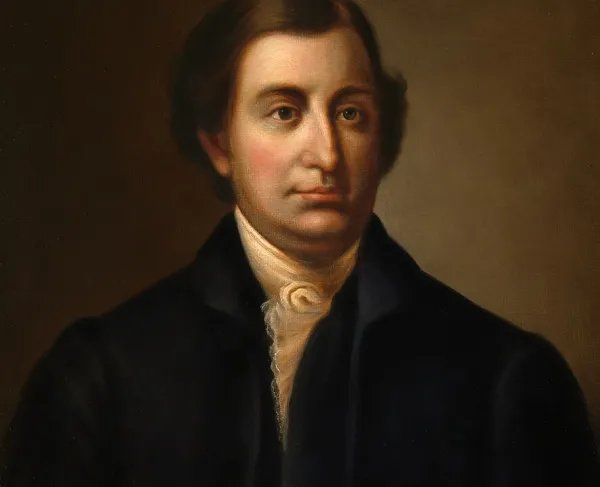

Edmund Randolph

Edmund Randolph was a Virginia lawyer and statesman who served in the Continental Congress during the American Revolution and afterwards as Governor of Virginia, the first U.S. Attorney General and second U.S. Secretary of State. At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he presented the Virginia Plan, which became the initial blueprint for the United States Constitution.

Randolph was born into a wealthy Virginia family in Williamsburg on August 10, 1753. His father, John Randolph, was Thomas Jefferson’s cousin. His grandfather was the only Virginian colonist to be knighted by the British King. Edmund received the best education available to Virginians at the time, studying at the College of William and Mary and afterward studying law with his father and uncle.

Meanwhile, tensions between the colonists and Britain heated up as Parliament imposed or re-imposed taxes and regulations on the colonies. Edmund’s father John, a vocal loyalist, received many threats and ill wishes in the years leading up to the Revolution. Despite this, John maintained a cordial relationship with his cousin Thomas Jefferson; the two exchanged letters and debated the merits of British rule. The younger Randolph, however, sided with the patriots, which was a source of tension in his family.

In April 1775, political activism escalated into war with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. John Randolph immediately became a target for patriot ire at the crown, putting his life in danger. Unsafe in Virginia, the elder Randolph made the painful decision to flee with his family to England. Edmund, just 22 years old, decided to stay behind and join the fight for American independence.

Edmund enlisted in the Continental Army and became George Washington’s aide-de-camp, helping the general write and deliver messages among other tasks. During this time, Edmund assisted Washington in the opening phases of the war, including the Battle of Bunker Hill and the Siege of Boston. Randolph’s military service lasted only a few months, however.

That October he received word that his uncle—Peyton Randolph, president of the Continental Congress—had died. Edmund returned to Virginia as executor of Peyton’s estate and while there was elected to the Fourth Virginia Convention. Shortly after, he was elected Mayor of Williamsburg, Virginia, and swiftly appointed Virginia’s attorney general. He was only 23 years old.

In 1776 he married Elizabeth Nicholas, the daughter of Virginia’s treasurer. The two had known each other since childhood and were extremely close. Throughout their marriage, they almost never quarreled. The rarity of their arguments caused their children to commit a rare instance to memory. One day when Mrs. Randolph was telling Edmund a story of some incident, he interrupted her, exclaiming “that is mere gossip.” Clearly annoyed at the accusation, Mrs. Randolph walked away and locked herself in her room. Edmund, realizing the misstep, walked over to the door of her room and gently knocked. No response. He then said, “Betsey, I have urgent business in town, but I shall not leave this house until permitted to apologize to you.” Mrs. Randolph opened the door, and the incident thus ended.

In 1779, Randolph began representing Virginia at the Continental Congress and served until 1782. Between congressional sessions, he managed a law practice, representing many of his associates in court, including George Washington. In 1786, Randolph was elected Virginia’s governor and, in that capacity, represented Virginia in the Annapolis Convention. The convention wanted to settle trade disputes between the states that came about under the Articles of Confederation government. The convention left many thinking that the Articles should be amended to help prevent future disputes between the states.

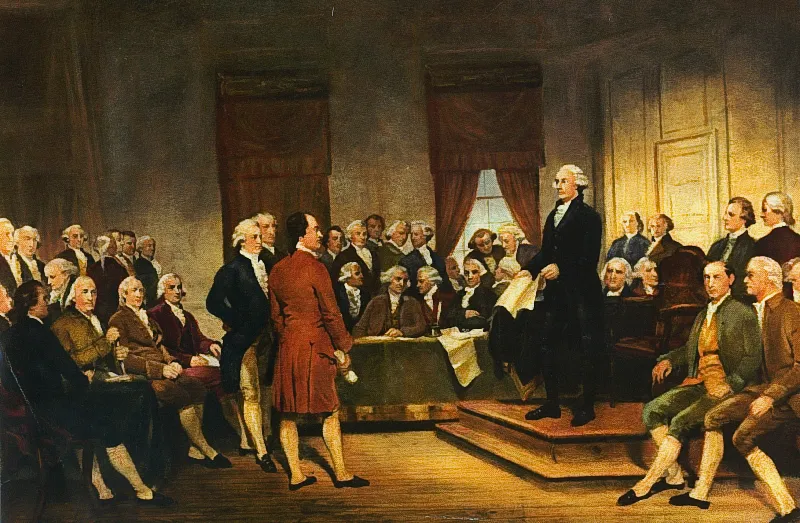

The next year a convention met to amend the Articles of Confederation. Randolph, as governor, and six other Virginians went to Philadelphia as representatives. One of the delegates, James Madison, however, had a radical idea. Instead of amending the Articles, the Virginians should present an entirely new plan for how to govern the United States. In the days leading up to the convention, Madison met with members of the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations to create and build support for his proposal. Edmund Randolph was a key ally and partner since he led the Virginia delegation. His input became a substantial part of the proposal.

When the delegates arrived at the State House in Philadelphia expecting to revise the Articles, Randolph ambushed them with the final document, called the “Virginia Plan.” It proposed a new federal government comprising three branches: an executive, a judicial, and a legislative. The legislative branch would be split into two houses, like the English Parliament, with an upper and a lower chamber. By putting forward the Virginia Plan right at the beginning, Randolph changed the agenda and dictated the course of the conversation, giving Madison’s plan the best chance for success. The Virginia Plan did not survive the convention unscathed, but the resulting “Connecticut Compromise” left much of its foundation intact, eventually becoming the Constitution of the United States.

Randolph, however, did not sign the Constitution. The final version did not include protections of individual rights, though its supporters said they would add those in as amendments after ratification. Randolph, unsatisfied with that answer, initially advocated against ratification. He feared that without such protections the constitution would destroy, rather than preserve liberty in America. In 1788, he presided over Virginia’s ratification convention. The delegation was fiercely divided down the middle. George Mason and Patrick Henry opposed ratification. They counted on Randolph’s support.

Nine states had already ratified the Constitution, the minimum amount for it to go into effect. Randolph feared what would happen if the rest of the states joined and Virginia stayed behind. To him, disunion was worse than the alternative. He shocked the convention when he said, “If after our best efforts for amendments, they cannot be obtained, I will adopt the constitution as it is.” In large part due to his support, Virginia became the 10th state to ratify the Constitution and by a razor-thin margin.

For his support, George Washington rewarded Randolph by appointing him the first United States Attorney General, a cabinet position. When Thomas Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State, Washington picked Randolph to take over. Throughout his time in Washington’s cabinet, Randolph walked a fine line between the opposing factions of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. While perhaps the best course for the country, this approach did not give him any allies, instead creating enemies. When Washington received an intercepted letter from the French ambassador, Joseph Fauchet, in which the ambassador angrily denounced the United States government, Randolph was held responsible. As Secretary of State, Randolph was tasked with keeping friendly relations with France, a key U.S. ally. With no one to take his side, Randolph resigned in disgrace, ending his political career.

Randolph returned to his home in Virginia where he resumed his law practice. In 1807, he defended Aaron Burr against accusations of treason, securing his acquittal. Shortly afterward, Randolph’s health began to fail, suffering from paralysis among other conditions. His wife died in 1810, leaving Edmund heartbroken. He died three years later, aged 60, on September 12, 1813.