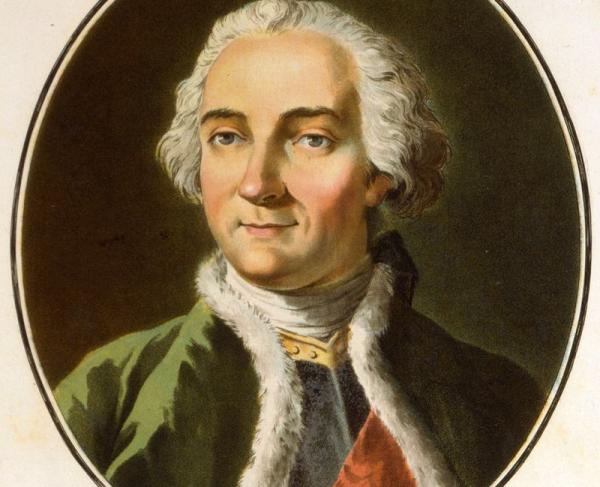

Edward Braddock

Born in 1695 to an officer of the Coldstream Guards, Edward Braddock seemed destined for a military career. At age fifteen, he received an appointment as an ensign in his father’s regiment and quickly rose through the ranks. In 1747, he commanded the British force alongside the Dutch military in the Siege of Bergen op Zoom in the Austrian War of Succession, and soon after he was appointed major general.

With his new promotion came a new assignment. The British inaugurated war with the French in North America n in 1754. The following year Braddock arrived in Virginia to command all British troops on the continent in an offensive against French fortifications. Soon after he landed in America, the general began coordinating with the governors of Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Massachusetts to determine what the colonies could contribute to his expedition. Some governors balked at Braddock’s dogged persistence, particularly the pacifist Quakers of Pennsylvania. Nonetheless the general successfully prepared to launch his expedition with the help of influential colonials like Benjamin Franklin.

Braddock planned four separate assaults on the French forts in New Brunswick, New York, and Pennsylvania. The forty-five year old general himself would lead the fourth assault on Fort Duquesne at the Forks of the Ohio River. Following some administrative and supply delays, Braddock and his column departed Fort Cumberland in Virginia and set out for Western Pennsylvania on May 29, 1755. Braddock’s officers included future Revolutionary War generals Thomas Gage, Charles Lee, Horatio Gates, and George Washington. Daniel Morgan and Daniel Boone served as teamsters.

The army moved slowly, cutting a road through the wilderness for wagons and artillery to pass. The road would also provide a means to supply Fort Duquesne once it fell to Braddock's men. But as the British trudged through the forest, the French made steady progress on the fort with each passing hour. To make up for his slow rate of movement, Braddock divided his army into a “flying column” of about 1,300 men to advance well beyond the wagons and reach Fort Duquesne sooner.

On July 9, 1755 Braddock and his men crossed the Monongahela River about ten miles south of Fort Duquesne. The advance guard of grenadiers under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage encountered a force of French and Indians soon after the crossing. Though the British unleashed several initial volleys to gain the upper hand, they soon found themselves in a crossfire despite outnumbering their enemy. Arriving columns from the rear prevented retreat— chaos ensued. Braddock attempted to rally his men but fell with a mortal wound. George Washington tended to the general before carrying him from the field with another officer.

The British army retreated in disgrace as their leader lay wounded in the back of a wagon. Braddock died on July 13 from his wounds suffered at the Battle of the Monongahela. He reportedly left Washington his sash and pistols. British soldiers buried Braddock just west of the Great Meadows where Washington surrendered at Fort Necessity nearly a year earlier. The general's grave allegedly lay in the middle of the road so that the Native Americans could not discover his body and desecrate it. Braddock’s defeat allowed the French to remain at the Forks of the Ohio for three more years.