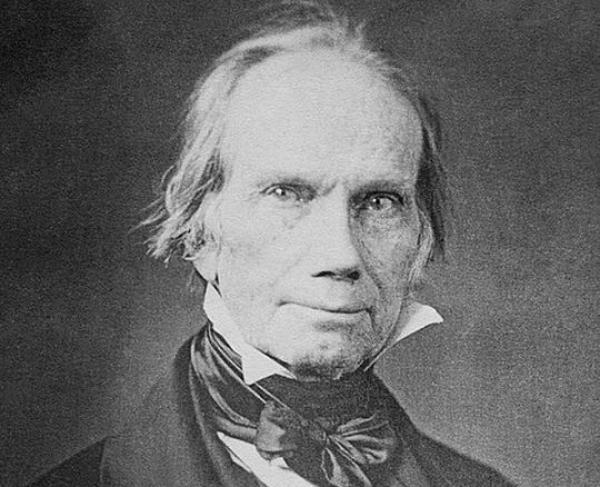

Henry Clay

Although never President, Henry Clay dominated the American political landscape in the first half of the nineteenth century and remains one of the most influential men in Antebellum America. In an era of shifting factions, "the Great Compromiser" stayed true to his nationalistic ideals throughout his entire career, even as his political party changed from Democratic-Republican to National-Republican to finally Whig.

Henry Clay was born during the midst of the Revolutionary War on April 12, 1777, in a farmstead in Hanover Country, Virginia. At the time of Clay’s birth, his father was a middle-class planter, who soon elevated himself to a member of the elite planter class by the time of his death four years after Henry’s birth. Despite his father’s early death, Clay was raised in Hanover County, yet he only received three years of formal education. However, his intelligence and charisma provided him with early success as a lawyer in Lexington, Kentucky before moving on to politics. Clay served as either a Congressmen or Senator intermittently from 1806 until his death in 1852 often resigning to run for President. Clay unsuccessfully ran for president three times: in 1824, 1832 and in 1844 and unsuccessfully sought his party’s nomination twice: in 1840 and 1848.

Clay maintained the reputation as "the Great Compromiser” throughout his career because he often favored and instigated compromise as opposed to the radical action that would propagate disunion, which is on par with his position as a nationalist. He first earned this reputation by helping to orchestrate the Missouri Compromise in 1820 which mediated contrasting northern and southern interests and tensions over the expansion of slavery. While Clay owned slaves, he wrote “no man is more sensible of the evils of slavery than I am, nor regrets them more” and as such was not an ardent supporter of slavery. Clay moved to Kentucky in the late 1790s and remained there for the rest of his life. As such, he represented western interests as opposed to his fellow members of the “Great Triumvirate,” Daniel Webster and John Calhoun who represented northern and southern interests respectively. Consequently, “Henry of the West” and “the Western Star” became additional nicknames of the Kentuckian.

Clay remained a hardened nationalist throughout his entire political career. As a War Hawk, he actively encouraged war with Great Britain and supported the policies that provoked the War of 1812. From 1815 onward, “the Western Star” supported a nationalistic economic agenda which included his infamous economic plan titled the American System. Under the American System, the United States government theoretically promoted economic growth through a system of internal improvements (especially transportation networks like roads, canals, harbors, etc.), a national Bank of the United States, and high tariffs to protect American industry. Clay believed that economic prosperity required federal intervention in the economy. While the American System made headway in transportation networks, it also led to an economic crisis in early 1824.

Clay remained at the center of a political scandal known as the “Corrupt Bargain.” As there was no victor in the Electoral College for the presidential election in 1824, the House of Representatives chose the President. As Speaker of the House, Clay united with candidate John Quincy Adams to deliver Adams the House vote in exchange for the Kentuckian serving as Adams’ Secretary of State. Their plan succeeded even though Andrew Jackson won the plurality of the Electoral College and the popular vote. This so-called “Corrupt Bargain” ruined Clay in Andrew Jackson’s eyes. This is unfortunate because while these men had their political differences, both were nationalists who could have been public allies during the Nullification Crisis.

The Nullification Crisis emerged in part because of Clay’s American System. His economic plan relied heavily on high protective tariffs. Congress passed the first protective tariff in 1816 after the War of 1812 ended and progressively passed higher tariffs each year until 1828 with what became known as the Tariff of Abominations. It is important to note that Clay opposed this tariff because he thought it was too high; however, Jackson already secured southern support for his presidential campaign and attempted to garner northern support by backing the tariff. This move would eventually come to haunt Jackson as in 1830 a large group of South Carolinian politicians and citizens threatened secession and propagated nullification. During this crisis, Clay maintained that federal authority trumped state authority; however, he worked toward a compromise with Congress trying to lower the Tariff of Abominations, which Jackson discreetly supported. The same day Congress passed Jackson’s force bill, they also passed Clay’s tariff reduction and “the Western Star” once again championed himself for his legislative compromise which adverted disunion.

Clay’s final act of compromise was the Compromise of 1850 which alleviated tensions resulting from the Mexican Cession. Pro-slavery and anti-slavery advocates debated if slavery should be allowed in the Mexican Cession and these debates represented the first time sectional loyalties transcended party loyalties on such a large scale. The Compromise of 1850 temporarily put off these debates because it did not include any provisions that limited slavery in the remainder of the Mexican Cession, besides admitting California into the Union as a free state, while making additional concessions to both northerners and southerners.

“The Great Compromiser” passed away in Washington D.C. on June 29, 1852, from tuberculosis. His death marked the end of the spirit of compromise in antebellum American politics as the 1850s served to be the most contentious decade prior to the Civil War which was wrought with stark sectional tensions. Despite Clay’s best efforts to instill compromise in American political debates over slavery would devolve into a Civil War.

Suggested Additional Reading: