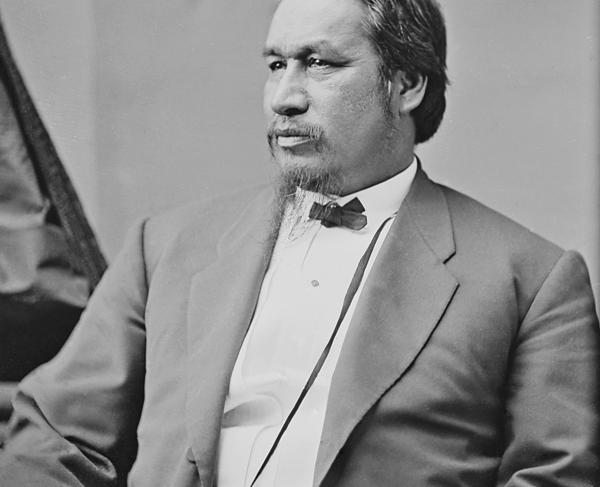

Henry A. Wise

Henry Andrew Wise was born on December 3, 1806, into a prominent landowning family. His father John was a major in the Virginia militia during the American Revolution and served in the state’s House of Delegates. However, he died in 1812, followed by his wife Sarah in 1813. The young orphaned Henry was taken care of by his aunts and grandfather. He was taught by private tutors until he was 12, after which he attended Washington College in Pennsylvania (currently Washington and Jefferson College), graduating in 1825. He only received a small inheritance of land, so he turned to law to make his fortune instead.

He studied law under a prominent lawyer in Winchester, Virginia, completing his studies in 1828. He then married Ann Eliza Jennings and the couple moved to Nashville where Wise practiced law. They became acquaintances of President Andrew Jackson. The couple had four children before Ann passed away in 1837. Wise remarried in 1840, to Sarah Sergeant, and had ten children with her, although only three survived infancy. He married for a third and final time in 1853, to Mary Elizabeth Lyons, and the couple had no children.

Wise returned to Virginia to tend to his modest farm “Only” on the Eastern Shore in 1830. It was there Wise leaped into Virginia politics, where he would remain for more than three decades. Although he was not wealthy and the Eastern Shore provided a poor political base, Wise was intelligent and a gifted public speaker. He gained the reputation of being a formidable debater.

In 1832, Wise narrowly won a heated election for a seat in the House of Representatives. He subsequently fought and won a duel against his defeated opponent. He was re-elected in 1834, right before splitting from the Democrats over Jackson’s refusal to recharter the Second National Bank. He served as a Whig for the rest of his time in the house, being re-elected three more times.

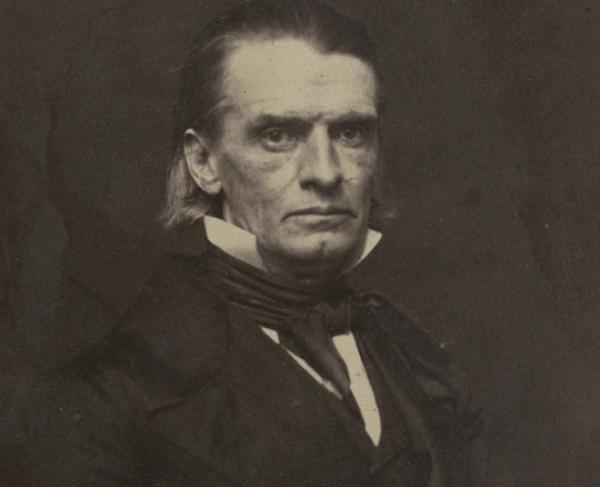

In Congress, Wise was an outspoken states’ rights supporter. During the Nullification Crisis, when South Carolina threatened to secede over a tariff they saw as unjust, he supported secession as a last resort and opposed the Jackson administration’s using of force to coerce the South Carolinians. His foremost enemy, however, was former president John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, a fellow Whig. In 1838, he served as the second of Congressman William J. Graves, of Kentucky, when he shot and killed Congressmen Jonathan Cilley, of Maine, in a widely-publicized duel that exemplifies the bitter hostilities in Congress in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Fellow Virginian John Tyler, when he became president in 1841, appointed Wise to the post of minister to Brazil, where he outspokenly criticized Brazil’s participation in the international slave trade.

Wise was an influential figure at Virginia’s constitutional convention in 1850-51, where a new constitution increased the political power of Western Virginia in the General Assembly. He also argued for internal improvements to foster economic development and for universal education. He successfully ran for governor in 1855 to fulfill these goals. He was initially a popular governor, supported by both Democrats and what was left of the Whig party. In order to satisfy both constituencies, he walked a fine line between slavery and union, especially as tensions grew more fraught. He tried satisfying both pro-slavery, states’ rights supporters and antislavery advocates by protecting both slavery and union.

However, Wise was soon forced to confront a crisis that destroyed any pretense that slavery and union could be protected simultaneously. On October 16, 1859, John Brown and a group of abolitionists raided the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, with the hope of triggering a massive slave uprising in the South. Brown was captured and tried by the state of Virginia, who sentenced him to death. Wise had the power to commute his sentence to imprisonment for life. Moderates and abolitionists urged him to commute the sentence, and he almost considered having Brown sent to a mental hospital instead, believing the man was insane. However, when he visited Brown in his jail cell, he decided that Brown was far from insane and allowed the death sentence to stand. On December 2, 1859, Brown was executed in Charles Town, Virginia (present-day West Virginia). Wise became a hero for Virginians, for stamping out a dangerous traitor, while he was vilified in the North as Brown became a martyr.

As 1860 election season neared, Wise considered running as a compromise Democrat, but the geographic split of the party destroyed any chance of an agreement. In the spring of 1861, as Deep South states seceded to form the Confederacy, Wise was elected as an influential delegate to the secession convention. He strongly advocated for disunion. He gave a fiery speech in which he claimed that a Shenandoah Valley militia, loyal to him personally, was on its way to Harpers Ferry to seize the arsenal, all the way brandishing a revolver. “Blood will be flowing at Harpers Ferry before night,” he declared. This controversial speech invited heated debate, as many viewed this action as outside the law, but Wise’s opinion won the day when Virginia voted to secede on April 17.

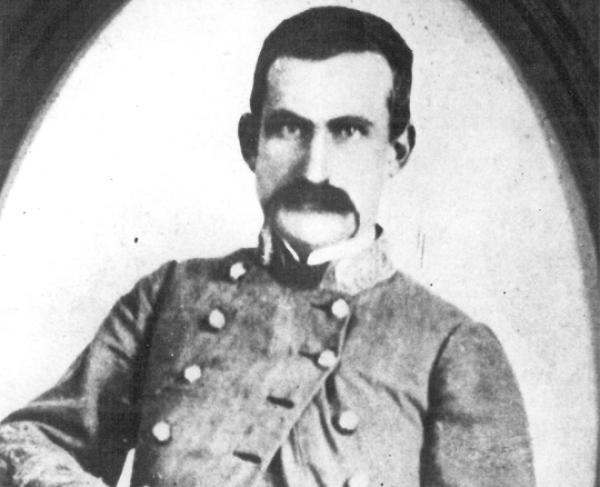

Wise was appointed as a brigadier general in the Army of Northern Virginia for political reasons; he had no military experience. He performed poorly in operations in the Kanawha Valley in 1861 and on Roanoke Island in 1862. However, Wise improved as the war went on, serving with distinction at Petersburg and during the Army of Northern Virginia’s final retreat to Appomattox Court House. He was temporarily promoted to major general at Sailors Creek but surrendered as a brigadier.

After the war, Wise never sought out an official pardon, but rather deemphasized the large role he played in Virginia’s secession. In 1872, he supported his former adversary Ulysses S. Grant’s re-election to the presidency. He worked as a lawyer until he passed away in Richmond on September 12, 1876.

Related Battles

8,150

3,236

3,500

4,250

1,150

8,830

152

500