Hercules Mulligan

An unsung hero of the Revolution, Hercules Mulligan was one of America’s most important spies.

Born in 1740 in Coleraine Ireland, he emigrated to New York City with his family at six years old. After graduating from King’s College, Mulligan married Elizabeth Sanders, the niece of Admiral Sanders of the Royal Navy. Quite irrespective of his wife’s British background, Mulligan was a staunch patriot. During the 1770s, Mulligan lived with his close friend Alexander Hamilton and was able to impart some of his flag-waving notions onto the young scholar. Often engaging in late night discussions, the two colleagues exchanged ideas in such a way that Hamilton’s desire for independence was unquestionably sharpened.

In 1774, Mulligan became a tailor and opened a storefront in New York that was frequented by the upper echelons of society. Even high-ranking British officers became regulars at his shop. Successful enough to afford assistance, Mulligan instead preferred to work personally with each of his clients, cultivating genuine relationships with both Americans and Brtitish alike. Despite fraternizing with British officers, the young patriot ensconced himself in treasonous affairs. He was one of the first colonists to join the Sons of Liberty and later the New York Committee of Correspondence, two organizations that sought to undermine British authority in the colonies.

When war broke out in 1775, Hercules Mulligan did his part to help the cause. Still in New York, he joined a volunteer militia that stole British cannons and helped lead the Sons of Liberty tear down a statue of King George III in Bowling Green. Once Washington retreated from New York, however, Mulligan was forced to remain in the city and return to his clothing emporium. It was at this juncture that Hamilton suggested Mulligan become a spy for the Continental Army. His proximity to the enemy made Mulligan an ideal candidate for espionage. The tailor eagerly accepted.

Throughout the war, Mulligan performed his new role perfectly. By outfitting verbose British officers, appealing to their egos, and asking the right questions, Mulligan gained valuable insight into the enemy’s movements. He could oftentimes deduce the British Army’s next move by inquiring when the officers needed their uniforms back. After gaining such intelligence, Mulligan dispatched his slave, Cato, to ride out to Washington’s headquarters with the news.

Twice, the spy’s information prevented General Washington from ruin. On one occasion, a rushed officer came to Mulligan late at night in dire need of a coat. Upon further questioning, the officer carelessly disclosed his mission to capture George Washington later that day. Mulligan sent for Cato immediately and upon receiving the news, Washington relocated to safety. In another instance, the British had caught wind of Washington’s plan to travel to Rhode Island via the Connecticut shoreline. By a stroke of luck, Hercules’s brother, Hugh, was charged with loading the British boats with supplies. Hugh informed Hercules of the enemy’s stratagem and Cato carried the message to Washington who quickly rerouted.

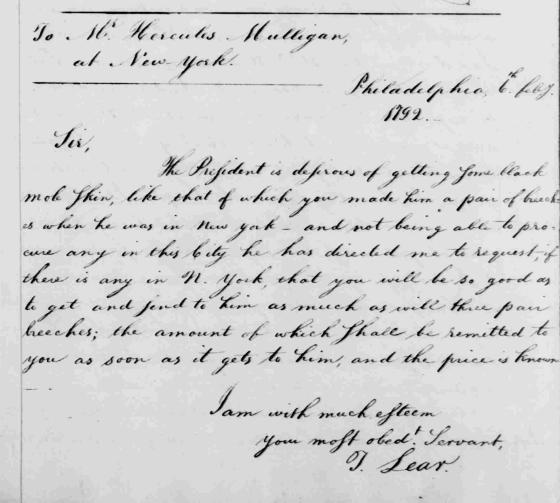

After the war, a grateful George Washington visited Mulligan’s store and requested new clothes. This was the War Hero’s way of protecting Mulligan from being labeled as a British sympathizer for working closely with the enemy. Outside his store, Mulligan proudly displayed a sign that read: “Clothier to Genl. Washington.”

In 1785, Mulligan continued to fight for democratic ideals and co-founded the New York Manumission Society. He died in 1825 at age 80 and is buried next to Alexander Hamilton in Trinity Church.