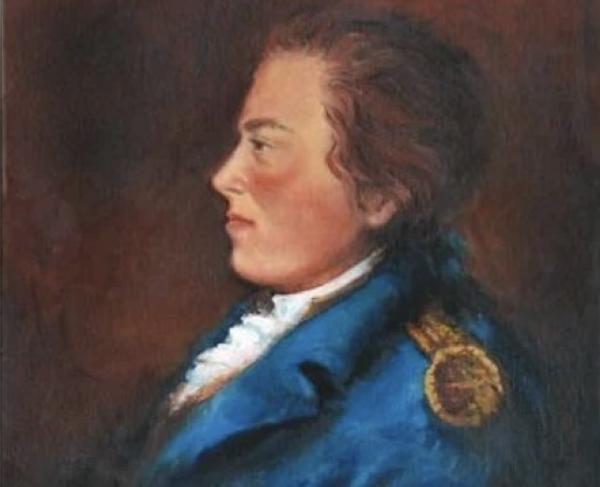

John Jay

The youngest son of French Huguenot refugees, John Jay was born on a farm in New Rochelle, New York, on December 12, 1745. His mother taught him until he was old enough to go to the French Huguenot Church School. At age 14, Jay entered King’s College (Columbia University), graduating in 1764. For a man who would spend much of his life in legal pursuits, he had no interest in studying law until his final year at King’s College.

After graduating with honors, he clerked for Benjamin Kissam, one of New York City’s most prominent attorneys. Jay’s fledging legal career was soon put on hold when New York’s lawyers went on strike to protest the Stamp Act. Not wanting to waste any time, Jay went back to King’s College to earn a Master of Arts degree.

Jay initially feared that the growing tensions between Great Britain and her North American colonies would lead to violence and mob rule. He favored reconciliation, wanting to salvage the relationship to prevent all-out war. However, his mind was changed on a diplomatic mission to London on behalf of the Continental Congress. He realized that British leaders wouldn’t take the colonies seriously unless they fought and won a war of independence.

Now a fervent revolutionary, Jay devoted himself to the cause of American independence. He was the second youngest delegate to the Continental Congress. He then returned to his home state of New York, where he served on its provincial congress and helped to approve the Declaration of Independence there. He also drafted the state’s first constitution and was elected its first chief justice. In 1778, Jay returned to national politics, becoming president of the Continental Congress at just age 33. The next year, he became minister to Spain, where he worked to solidify the Spanish empire’s support for the revolution. In the closing act of the revolution, Jay, along with Benjamin Franklin, traveled to Paris to negotiate peace with Great Britain and won surprisingly liberal terms for the former colonies through the Treaty of Paris (1783).

Almost as soon as the United States established itself as a nation under the Articles of Confederation, Jay was made Secretary for Foreign Affairs. However, he became increasingly frustrated and disillusioned by the Articles. Jay, as well as a growing number of Americans, saw that the Articles were ineffective and needed to be replaced by a stronger central government.

Jay became one of the forefront defenders of the new U.S. Constitution, the document drafted in Philadelphia in 1787 to replace the Articles. He collaborated with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison on The Federalist Papers, a series of anonymous articles defending the new Constitution.

After the Constitution was ratified and adopted as the law of the land, largely thanks to The Federalist Papers, Jay was appointed by President George Washington to be the country’s first chief justice of the United States Supreme Court. As was the case for nearly every early American leader, Jay set precedents that are still followed today. In Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), Jay argued for the separation of powers and ruled that state power was subordinate to that of the federal government. While this would become a more widely accepted notion in the years to come, the hostile reaction of the public to Jay’s decision would lead to the passage of the 11th Amendment, which declared that the federal court did not have authority in cases where a private citizen was suing a state.

After retiring from his post as chief justice, Jay was sent as a special envoy to Great Britain to settle grievances left over from the revolution, some of which included disputes about the western frontier and commercial relations. The subsequent treaty, which forever became known as the Jay Treaty, was approved by the Washington administration but was lambasted by Jeffersonians for favoring the British in favor of Americans. Jay was called a traitor and burned in effigy; before the treaty, he had been seen as a possible successor to Washington for the presidency, but now all presidential hopes were ruined.

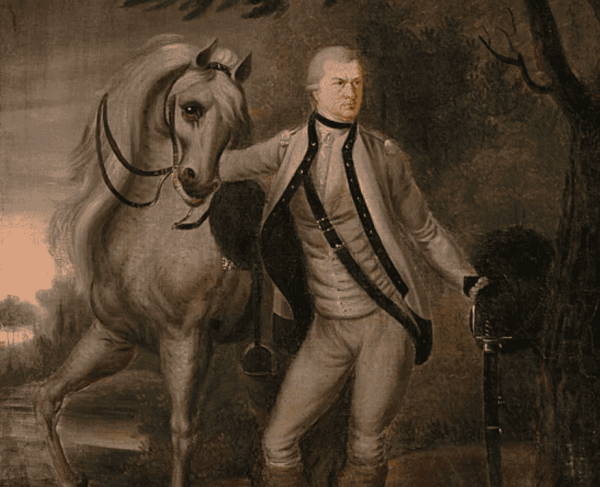

With help from New York Federalists such as Hamilton, Jay was elected governor of New York, even before he stepped off the boat from England. He successfully served from 1795 to 1801, earning the respect and admiration of Federalists and Jeffersonians alike. This immensely popular governor reformed the state’s court and penal system and abolished slavery, as well as bolstered the Empire State’s economy through extensive infrastructure projects.

In 1801, Jay declined overtures from President John Adams to return as chief justice. Instead, when his term as governor ended, he retired to public life and spent the rest of his life on his farm. He passed away in 1829, surviving both of his Federalist Papers co-authors.