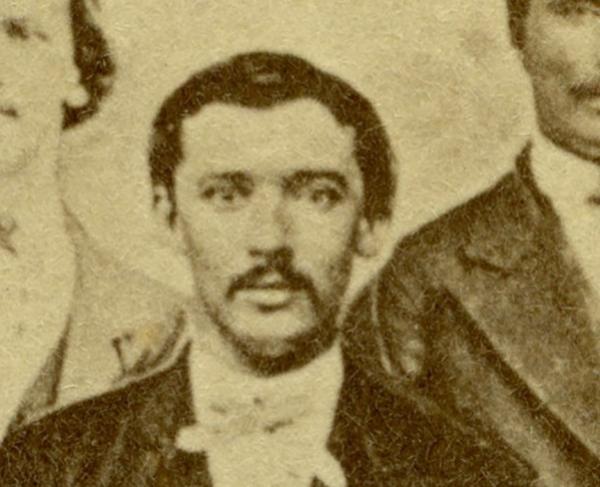

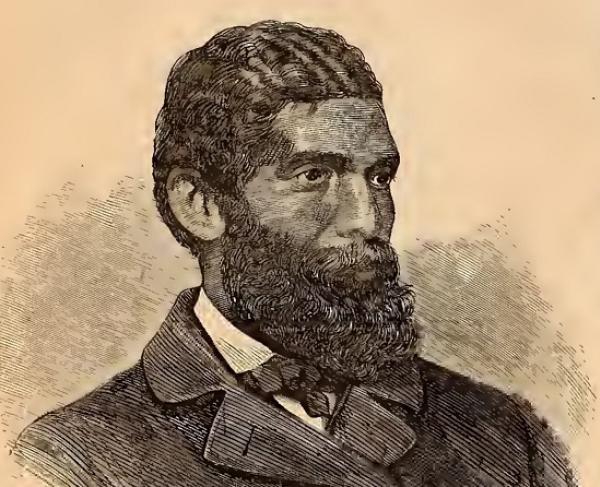

John S. Rock

On February 1, 1865, the day after the House of Representatives passed the 13th amendment, John Swett Rock of Boston became the first African American ever admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of the United States. Many toil their entire lives to achieve such an honor. For Rock, who had already won acclaim as a teacher, dentist, and doctor — all before turning 30 — it was merely the latest in a long list of accomplishments.

Born in Salem, New Jersey on October 13, 1825, John Rock evinced remarkable talent and determination from an early age. While still a teenager — and having only recently completed his own education, he was offered a job teaching in Salem’s public schools. Over the next four years he won the admiration of his colleagues, one of whom remarked that Rock’s “was certainly the most orderly, and the best conducted, school I ever visited, although myself a teacher for nearly twenty years.”

While he dedicated his days to educating others, Rock dedicated his nights to self-improvement, studying medicine in the hopes of gaining admission to medical school. When he was denied admission because of his race, however, he changed his focus and apprenticed under a local dentist. In 1849, after completing his training, he moved to Philadelphia, opening his own practice. Crafting award-winning false teeth, he proved to be as skilled at dentistry as he had been at teaching.

Unfortunately, Rock found it difficult to earn a living because most of his patients were low-income African Americans. What’s more, he had not abandoned his dream of becoming a doctor. After another stint as an educator, he was accepted by the American Medical College in Philadelphia. Excelling as a student, he graduated in 1852, becoming one of the first African Americans to earn a medical degree.

By this time Rock was also starting to gain distinction for his work in the causes of temperance and abolition. Perhaps drawn by the city’s reputation as the epicenter of anti-slavery seand other moral reform movements, he chose to set up his new medical and dental practice in Boston. Over the next several years he rose to even greater heights, emerging as a leader in Boston’s free black community and winning national recognition as a reform lecturer. One of his lectures was so popular that he was invited to deliver it before an audience in the hall of the Massachusetts House of Representatives.

In the late 1850s Rock’s health began to suffer, likely as a result of the onset of tuberculosis. Unable to continue lecturing or practicing medicine, he decided to travel to Paris to receive more advanced treatment. His application for a passport, however, was rejected. A passport was “a certificate of citizenship,” and the Southern-dominated federal government was unwilling to recognize African Americans as citizens, especially after the Dred Scott decision.

Defying the will of the Buchanan administration, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts began granting its own passports to African Americans, allowing Rock to leave for Paris in the spring of 1858. Still too unwell to resume his medical practice upon his return in early 1859, he returned to the lecture circuit.

He was once again invited to speak at the Massachusetts State House, this time to deliver a lecture in which he used the “character and writings of Madame de Staël,” one of Napoleon Bonaparte’s principal critics, to argue that women were “the intellectual equal” of men. One glowing newspaper review marveled, “Thus, a thinking, educated, German, and French speaking negro, converses and instructs a select American audience on female intelligence and literature of the past times, in the Hall of the House of Representatives of one of the first States in the Union!”

Not content with excelling as a teacher, dentist, physician, activist, and public intellectual, Rock embarked on a study of the law, successfully passing the Massachusetts bar in September 1861. During the Civil War, while continuing to practice law, Rock threw his energies into recruiting African Americans for the Union Army, helping to fill the ranks of the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiments.

Determined to rise ever higher, Rock set his sights on admission to the bar of the Supreme Court. When he achieved that distinction, the Boston Journal crowed that, “The slave power, which achieved its constitutional death-blow yesterday in Congress, writhes this morning on account of the admission of a colored lawyer, John S. Rock of Boston, as a member of the bar of the Supreme Court of the United States.”

Unfortunately, Rock’s health continued to decline. He died on December 3, 1866, having achieved more in 41 years than most accomplish in a lifetime.