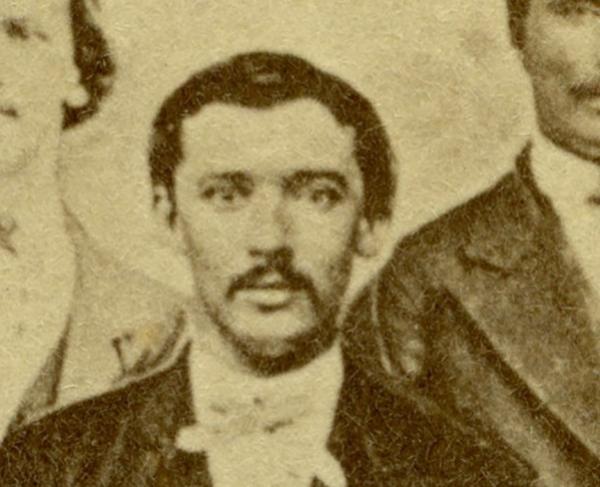

John T. Wilder

Endowed with a sense of independence that rivaled many of his contemporaries, John T. Wilder nevertheless typified the volunteer soldier of the American Civil War.

Born in the Catskill Mountains of New York, Wilder was descended from a long line of patriots. Both his grandfather and great grandfather fought in the War for Independence (the latter losing a leg at Bunker Hill) and his father took part in the War of 1812. But as westward expansion and the rise of industry proved to be the dominating forces of the early Nineteenth Century, the young Wilder was swept away. By age 19 he had left his home for Ohio where, penniless, he found work as a draftsman and later as an apprentice in a foundry in Columbus. Very intelligent, Wilder learned much during this time and in 1857 he established a foundry of his own in Greensburg, Indiana. By 1860 Wilder had become an inventor and expert in the field of hydraulics.

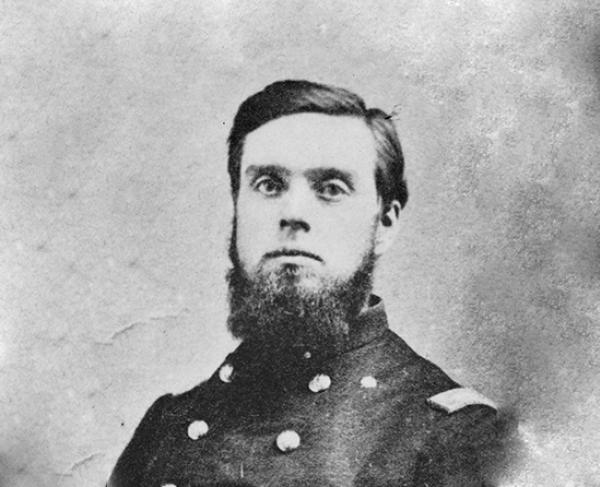

At the war’s outset in 1861, Wilder enlisted as a private in the First Indiana battery and—no doubt owing to his technical facility—was quickly elected captain. Two months later Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton commissioned him the lieutenant colonel of the Seventeenth Indiana Infantry. By the spring of 1862, the inventor-turned-soldier would be leading the regiment into its first battle as its colonel. Following his baptism by fire at the Battle of Shiloh, Wilder received recognition from his superiors for his potential and was quickly given command of a brigade. Soon after Wilder began to demonstrate the strange brand of independence that would become the hallmark of his military career.

Stationed at Munfordville, Kentucky in September of 1862, Wilder found himself in command of a garrison of less than 2,000 as advanced elements of Gen. Braxton Bragg’s 25,000-man Army of the Mississippi made their way through the Bluegrass State. The town’s railroad bridge over the Green River made Munfordville a crucial transportation hub for both armies, and Wilder was determined to hold it. Late on September 13, 1862, Confederate Brigadier General James R. Chalmers demanded the garrison’s surrender. The Hoosier colonel responded that he and his men would “try fighting for a while.” Chalmers’s assault on the morning of the 14th was met with spirited resistance from Wilder’s men who inflicted 283 casualties on the Rebels, losing just 37 of their own number. Southern reinforcements, however, were streaming in by the score; the Federals, on the other hand, could only manage a handful of additional troops, totaling around 4,000 men. In the face of a growing enemy force and repeated entreaties to surrender, Wilder and his men realized they could not hold out for long. After midnight on September 17, a blindfolded Wilder was escorted into enemy lines to meet with his adversary, Munfordville native Maj. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner. He had come to ask the general’s advice. Sympathetic to the colonel’s plight, Buckner allowed Wilder to observe the Rebel positions facing his men. At the conclusion of this interview Wilder said, “Well, it seems to me that I ought to surrender.” The following morning, the entire Union garrison at Munfordville surrendered with full military honors. Wilder spent the next two months in a Confederate prison.

When Wilder returned to his command at the end of 1862, it was clear that his stint in captivity had done little to diminish his audacity. In March of 1863, after his troops unanimously voted to adopt the Spencer repeating rifle, the colonel once again displayed his penchant for innovation—and his complete disregard for army red tape—by taking it upon himself to rearm his entire brigade with private funds loaned from Indiana bankers. At the same time, Wilder received permission to raid the Tennessee countryside for horses in order to reorganize his outfit as mounted infantry. Armed with state-of-the-art weapons and, now, mounted, Wilder’s four regiments became an integral instrument in the Army of the Cumberland’s 1863 campaigns, often on detached missions or in advance of the army.

During the June 1863 Tullahoma campaign Wilder’s men succeeded in driving Confederates from Hoover’s Gap, winning a key victory for Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, and earning themselves the moniker “Wilder’s Lightning Brigade.” Later that summer, Wilder, reinforced by elements of Thomas Wood’s division, led a diversionary action in front of Chattanooga, and eventually captured the city. During the battle of Chickamauga that autumn, Wilder’s men proved themselves to be indispensable, first protecting the army’s flank at Alexander’s Bridge, then, on the second day of battle, launching a counterattack around then through “Bloody Pond.” For his performance at Chickamauga, XIV Corps commander Maj. Gen. George Thomas recommended that Wilder be promoted to brigadier general.

Though brevetted to brigadier general in August of 1864, ill health plagued Wilder during much of the war’s penultimate year and in October he resigned his commission. After the war, he eventually settled in Chattanooga and established an ironworks manufacturing iron and rails for the railroad industry. His prominence grew along with his business ventures, and he was elected the city’s mayor in 1871. In his twilight years he held a number of other political positions, among them commissioner of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park. John T. Wilder died in Jacksonville, Florida at age 87. He is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Chattanooga.