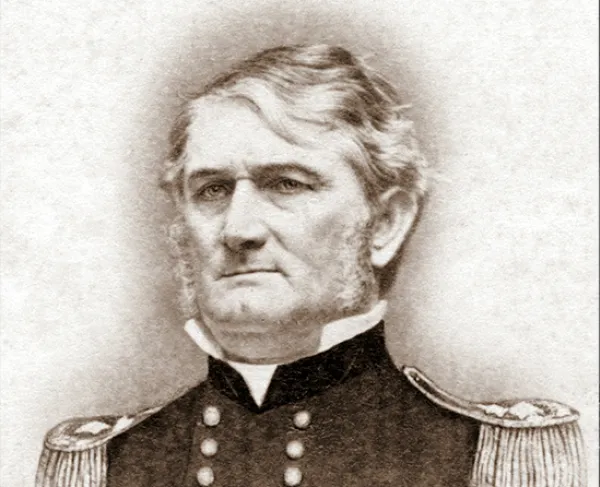

Leonidas Polk

Born April 10, 1806 near Raleigh, North Carolina, Leonidas Polk led a long and colorful life that was cut short by a cannonball in 1864.

He was raised by extremely wealthy parents. The family owned more than 100,000 acres of land. He excelled at the University of North Carolina and went on to West Point. Shortly after graduation, however, he resigned his military commission to focus on religious life.

By 1838, he was a prominent Episcopal Bishop living in Maury County, Tennessee. In 1860, he began construction of the University of the South in the mountains of Sewanee, Tennessee. When the war came, his friendship with West Point classmate Jefferson Davis won him a commission as a major general in the Confederate States Army. He had no military experience beyond his time at West Point, where he ranked 8th in a class of 38.

Much authority was granted to Major General “Fighting Bishop” Polk, but his military qualities were lacking. Upon taking command, he ordered an expedition into Columbus, Kentucky. Since Kentucky was officially neutral, Polk’s 1861 incursion prompted the state to call for Northern aid. A potentially invaluable strategic asset was largely lost to the Confederacy.

In 1862, Polk commanded troops at the Battles of Shiloh, Perryville, and Stones River. Bad blood developed between Polk and his superior officer, Braxton Bragg, due to Polk’s refusal to follow orders during the Perryville Campaign. A close friendship with Jefferson Davis sustained Polk’s military status throughout the war. He was also loved by his men, due in large part to his geniality, commanding presence, and lax attitude towards discipline.

The 1863 Battle of Chickamauga ended in Confederate victory, but Braxton Bragg again accused Polk of disregarding and critically delaying orders while in command of roughly half of the army. In response, Jefferson Davis transferred Polk to take charge of a military department encompassing most of Mississippi from December 1863-May 1864.

Polk came back to the Army of Tennessee, his old unit, just before Union General William Sherman launched his campaign towards Atlanta on May 4. This move prompted the fierce “Hundred Days Battles” between Chattanooga and Atlanta.

On June 14, 1864, in the midst of the titanic conflict, Polk and a group of fellow officers rode to the top of Pine Mountain in order to better examine the Union positions in the valley below. Riding along the blue lines, General Sherman spotted the officers through a spyglass. He ordered cannons to fire on the group. The first shot scattered the Confederates and the second tore through Polk’s body. He was killed and brought back through the army lines on a litter. Private Sam Watkins remembered the moment:

“He was as white as a piece of marble, and a most remarkable thing about him was, that not a drop of blood was ever seen to come out of the place through which the cannon ball had passed. My pen and ability is inadequate to the task of doing his memory justice. Every private soldier loved him. Second to Stonewall Jackson, his loss was the greatest the South ever sustained. When I saw him there dead, I felt that I had lost a friend whom I had ever loved and respected, and that the South had lost one of her best and greatest generals.”

Watkins also called Polk “our old leader, whom we had followed all throughout that long war.” The Bishop had strategic shortcomings, but he was a living banner of the Confederate forces of the West. His loss was deeply felt by the Army and the southern people.