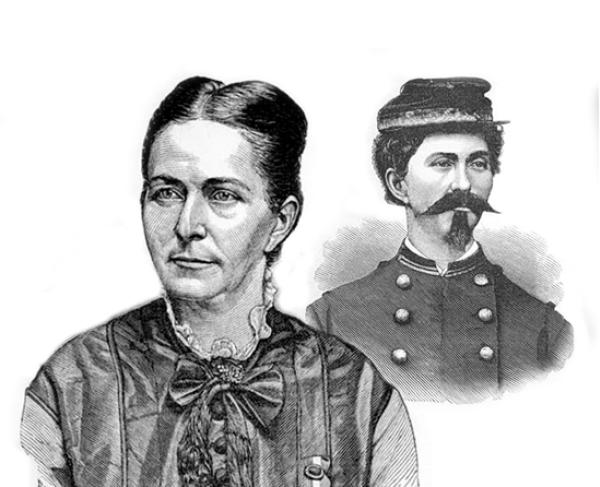

Loreta Janeta Velazquez

Just about everything that historians know about Loreta Janeta Velazquez comes from her book, The Woman in Battle: A Narrative of the Exploits, Adventures, and Travels of Madame Loreta Janeta Velazquez, Otherwise Known as Lieutenant Harry T. Buford, Confederate States Army. Some of the incidents in the book have been verified, but there are many facts still in question.

What is known is that Velazquez was born in Cuba on June 26, 1842 to a wealthy family. In 1849, she was sent to school in New Orleans, where she resided with her aunt. At the age of 14, she eloped with an officer in the Texas army. When Texas seceded from the Union in 1861, her husband joined the Confederate army and Velazquez pleaded with him to allow her to join him. Undeterred by her husband’s refusal, Velazquez had a uniform made and disguised herself as a man, taking the name Harry T. Buford.

Now displaying the self-awarded rank of lieutenant, Velazquez moved to Arkansas, where she proceeded to raise a regiment of volunteers. Locating her husband in Florida, Velazquez brought the regiment to him, presenting herself as their commanding officer. Her husband’s reaction is not recorded in history, as just a few days later he was killed in a shooting accident.

Velazquez headed north, acting as an “independent soldier,” she joined up with a regiment just in time to fight at the Battle of First Manassas (Bull Run) and the Battle of Ball’s Bluff. Shortly afterwards, she once again donned female attire and went to Washington, DC, where she was able to gather intelligence for the Confederacy. Upon her return to the South, Velazquez was made an official member of the detective corps.

Apparently espionage did not hold enough excitement for Velazquez, and she once again sought action on the battlefield. Resuming her disguise as Lieutenant Buford, she traveled to Tennessee, joining up with another regiment to fight at the Battle of Fort Donelson on February 11, 1862. Velazquez was wounded in the foot, and fearing that her true gender would be revealed if she sought medical treatment in camp, she fled back to her home in New Orleans.

Still in her male disguise, Velazquez was arrested in New Orleans for being a possible Union spy. She was cleared of the charges, but was fined for impersonating a man, and released. She immediately headed back to Tennessee, in search of another regiment to join. As luck would have it, she found the regiment she had originally recruited in Arkansas, and fought with them at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6-7, 1862. While on burial detail, she was wounded in the side by an exploding shell, and an army doctor discovered her true gender. Velazquez decided at this point to end her career as a soldier, and she returned to New Orleans.

Not content to sit out the rest of the war, Velazquez then went to Richmond to volunteer her services as a spy. She was able to travel freely in both the South and the North, working in both male and female disguises. It was during this time that she married Confederate Captain Thomas DeCaulp; unfortunately, he died in a hospital a short time later.

After the war, Velazquez married a man identified only as Major Wasson, and immigrated to Venezuela. After his death, she moved back to the United States, where she traveled extensively in the West, and gave birth to a baby boy. In 1876, Velazquez, in need of money to support her child, decided to publish her memoirs. The Woman in Battle was dedicated to her Confederate comrades “who, although they fought in a losing cause, succeeded by their valor in winning the admiration of the world.” The public reaction to the book at the time was mixed—Confederate General Jubal Early denounced it as pure fiction—but modern scholars have found some of it to be quite accurate.

With the release of her book, Velazquez may have married for a fourth time and is last documented as living in Nevada. The date of her death is thought to be 1897, but there is no supporting evidence for this. In response to those who criticized the account of her life, she said that she hoped she would be judged with impartiality, as she only did what she thought to be right.