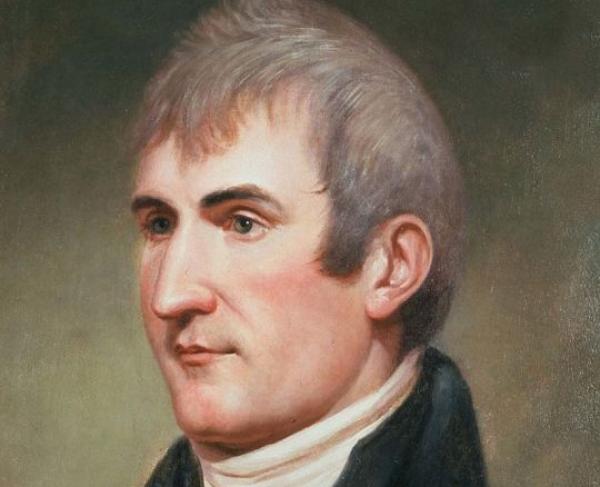

Meriwether Lewis

When Thomas Jefferson purchased the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803, he understood that very few Americans, including himself, had an idea about what lay within the land he had just spent fifteen million dollars to purchase. To rectify this issue, Jefferson formed the Corps of Discovery to explore the territory and potentially beyond, choosing a man to lead it who Jefferson believed held “a complete science in botany, natural history, mineralogy & astronomy, joined the firmness of constitution & character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods and a familiarity with the Indian manners and character, requisite for this undertaking.” To Jefferson, that man was his very own aide and US Army Captain Meriwether Lewis.

Like Jefferson himself, Lewis was born in Albemarle County, Virginia in 1774, the son of William Lewis, a lieutenant in the Continental Army. As a member of Virginian high society, the Lewis family could claim ties to both Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. Sadly, William Lewis died of pneumonia when his son was five, and so Meriwether spent most of his formative years in Georgia with his mother Lucy and stepfather John Marks. Young Meriwether took to frontier life like a fish to water, as Jefferson notes that “he habitually went out, in the dead of night, alone with his dogs, into the forests to hunt the racoon and opossum.” During this time his mother also taught him a good deal of amateur botany and herbology, and he likely encountered many members of the Cherokee Nation who lived near the same river valley as Lewis. Moving back to Virginia at the age of 13, Lewis finally began some form of schooling and private tutoring, and graduated from Liberty Hall Academy, now Washington and Lee University, at age 19 and joined the Virginia militia. After serving under President Washington to put down the Whiskey Rebellion, Lewis then joined the US Army as an Ensign in 1795, rising to the rank of Captain by 1800.

Thomas Jefferson claimed to have known Captain Lewis since the latter’s boyhood, as they both lived in the same county and walked among the same social circles, so when the former took the presidency the following year, he offered Lewis a position as his own private secretary. Lewis accepted and remained by the president’s side for two years accompanying him in both professional and social functions, until Jefferson then appointed him to command the new Corps of Discovery. Jefferson assigned a variety of tasks to Lewis, such as ascertaining and cataloging the natural history of the lands beyond the Mississippi and making contact with any indigenous nations who lived there. But most important of all was discovering if some sort of water passage existed to the Pacific Ocean, which explorers and colonists had searched for since Europeans first made landfall in North America. To aid him, Lewis recruited his fellow Virginian and former commanding officer in the Army, William Clark. The expedition commenced on the 16th of May 1804, with about 31 members. Despite his self-taught background on the subject, Lewis was a meticulous and observant naturalist and ethnographer and took careful notes on subjects ranging from local flora and fauna to Indian cultural practices. The following passage, a description of a slain grizzly bear from what is now Yellowstone Park, provides a good example of this:

“The legs of this bear are somewhat longer than those of the black, as are its talons and tusks incomparably larger and longer…Its color is yellowish brown; the eyes small, black, and piercing. The front of the forelegs near the feet is usually black. The fur is finer, thicker, and deeper than that of the black bear. These are all the particulars in which this animal appeared to me to differ from the black bear. It is a much more furious and formidable animal, and will frequently pursue the hunter when wounded. It is astonishing to see the wounds they will bear before they can be put to death. The Indians may well fear this animal, equipped as they generally are with their bows and arrows or indifferent fusees (sic); but in the hands of skillful riflemen, they are by no means as formidable or dangerous as they have been presented.”

Along the way, in Sioux territory, Lewis encountered a French trader named Toussaint Charbonneau and his 16-year-old Shoshone wife Sacagawea, both of whom joined the expedition and the latter of whom proved to be of great value in both finding a path through the Rocky Mountains and negotiating with local Native Americans along the route to the Pacific. Ultimately, Lewis and company failed to find a reliable water passage to the Pacific, but the notes he took and the biological samples he sent to President Jefferson were valuable resources in their own right.

After returning to Washington from the Pacific Coast in 1807, Jefferson appointed Lewis as governor of the Louisiana Territory. Lewis made his home in St. Louis and began negotiating trade deals with local Native Americans and planning infrastructure projects, often investing his own money into the territory, but unfortunately his many talents did not necessarily translate to effective civil administration. His record was heavily disputed by his secretary Frederick Bates, whose letters to Washington managed to convince the War Department not to assist Lewis in managing his expenses, causing his creditors to grow increasingly agitated and Lewis to fall deeper and deeper into debt.

Lewis’ death in 1809 is also something of a controversy. Those who came close to witnessing it only reported hearing some voices within a cabin in Tennessee, a gunshot and Lewis body lying alone. Jefferson and William Clark believed the death to be a suicide, noting his melancholic nature and possible troubles with alcohol, while Lewis’ mother Lucy believed her son was murdered, likely by highwaymen, which were common in that area. Modern historians have continued the debate to this day.

Regardless of the exact circumstances of his death, the loss of Meriwether Lewis was certainly a tragedy, as America had the life of one of its most adventurous and knowledgeable minds cut short. Though temporarily forgotten, Meriwether Lewis and the expedition he led greatly increased the early Republic’s knowledge about the lands beyond the Mississippi and undoubtedly contributed to the later trend of Westward Expansion.