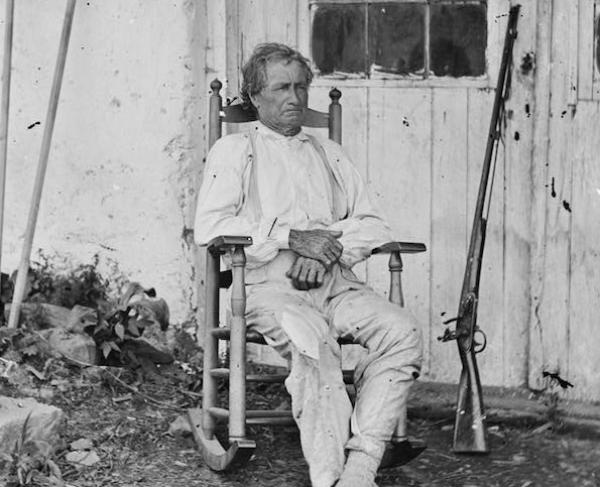

Noah Brooks

Noah Brooks, Abraham Lincoln’s best friend, was described as “a very comfortable and pleasant looking person... amiable and genial, full of anecdote, reminiscence and narrative.” He was known for his “genial and social nature” and “personal charm.” Brooks made many friends with his outgoing personality and was very well connected in New York through his many clubs. From childhood, Brooks was enthusiastic about literature, poetry, writing, and the arts.

Brooks, orphaned at a young age, was raised by his older sisters at home in Maine. He attended elementary and private school, where he was involved in theatre and became entranced by poetry. He went to Boston to become a landscape artist, became involved in clubs in the city, and committed himself to learning fine arts. In Boston, he wrote for The American Union, and in beginning 1851, under the pseudonym “Jacques,” Brooks wrote for The Carpet-Bag. His writing productivity in Boston increased his recognition as a newspaper editor.

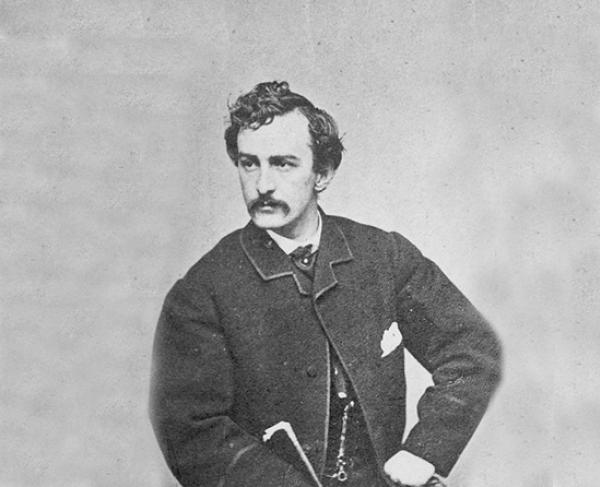

Brooks did not achieve great financial success in Boston, so he relocated to Dixon, Illinois, where he had family working as merchants. One relative helped him set up a painting shop where he advertised that he could paint horse carriages, homes, signs, and decorations. He outsourced painters, but later sold the business. Despite this, in 1856, Brooks continued to struggle with finances, and his marriage to Carolina Augusta Fellows rendered him destitute. While in Dixon, Brooks was involved with the Republican Party, and his political work brought him one of the most significant friendships of his lifetime. During a meeting of the Dixon Republicans on July 17, 1856, Brooks met Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln. During Lincoln’s stay in Dixon, he and Brooks conversed on five or six separate occasions and became friends.

Brook’s financial problems spurred him, like thousands of others, to travel westward in search of gold. He joined the established pattern of going with a small community— in Brooks’ case, seven other people— and headed toward Pikes Peak, Colorado to mine for gold. This treacherous westward march tragically led to the death of one of his companions. After arriving in Fort Laramie, the seven remaining travelers opted to go to California and not turn to go to Pikes Peak. Brooks ended up in the third most prominent California city, Marysville. He earned money by completing miscellaneous tasks and later, likely in the early months of 1860, once again owned a painting business.

In Marysville, Brooks’ writing career and emotional well-being flourished. He wrote for newspapers about politics and became heavily involved in the Marysville community. However, after the death of Caroline and her newborn son on May 21, 1862, Brooks’ priorities shifted. After the tragic death of his family, he pursued other interests. Brooks had been enthusiastic about politics and the Civil War, as seen in his fundraising efforts to help Union soldiers. On November 1, 1862, Brooks departed from California and for Washington, D.C., where he remained for over two years. In this time, Brooks still worked as a writer for Sacramento’s newspaper, the Daily Union, under the pseudonym “Castine.”

Brooks’ and Lincoln’s friendship was rekindled after Lincoln heard that Brooks was in the capital. According to Brooks, Lincoln “immediately sent word that he would like to see me, ‘for old times’ sake.” Upon reuniting, Lincoln said, “Do you suppose I ever forget an old acquaintance? I reckon not.” From that point forward, no more than a few days pass without Brooks and Lincoln spending time together. At one point, Brooks moved from his home in Georgetown to a stone’s throw from the State Department. Brooks became very close friends to both Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln. Lincoln said Brooks was so important to him that “no man outside of my own family circle [who] was ever so much to me.” In fact, Mary Lincoln only carried recollection of three individuals while she was suffering from mental afflictions in 1875, and Brooks was one of them. However, death once again prompted Brooks to move. After his dear friend was assassinated and the Civil War ended, there was no reason for Brooks to remain in Washington. He was appointed as a naval officer to the Naval Examining Board, a well-paying position. After Lincoln’s death, Mary gave him one of Lincoln’s canes, and the two kept in touch after Brooks left Washington.

In the summer of 1865, Brooks returned to California, where he lived in San Francisco. His appointment as naval officer was short lived because of the political conflicts he had with President Johnson, likely caused by Brook’s sardonic representation of Johnson’s inauguration. After this, Brooks shifted back to his writing and became the San Francisco Daily Times managing editor.

Brooks also took on the same position for the Alta California in San Francisco, where he edited and printed poems by Mark Twain. Twain said that Brooks was “a man of sterling character and equipped with a right heart.” For the Overland Monthly, Brooks wrote fifteen fiction stories directed toward younger audiences.

Ever the nomad, Brooks longed to be with the other community of writers that was emerging in New York City, so he requested a position at the New York Critic. In 1881, he came back to New York and flourished as a writer. He became involved in the most prestigious New York Club, the Century Association, as well as the Lotos Club, the New English Society, and the Author’s Club. In these clubs, Brooks was “everybody’s friend” and likely had a knack for being social because he had “a kind word and helping hand for every needy or unfortunate person.”

Brooks secured finances and comfort and so in 1894, he decided to write a book about his time with President Lincoln. Brooks called it his “life-work” and that “when it is completed I shall feel that I shall never do anything more important to me or to the literature of the time.” He left Newark, New Jersey, where he had been living and working since 1884 as Newark Daily Advertiser editor-in-chief, and moved back to Castine, Maine, his hometown. He did much traveling, including living in New York, and going back between California, Castine, and New York. He went back to California and lived in San Francisco but was ill with chronic bronchitis. He died on August 15, 1903, and was laid to rest in the cemetery in Castine.

Further Reading:

Lincoln’s Confidant: The Life of Noah Brooks By: Wayne C. Temple