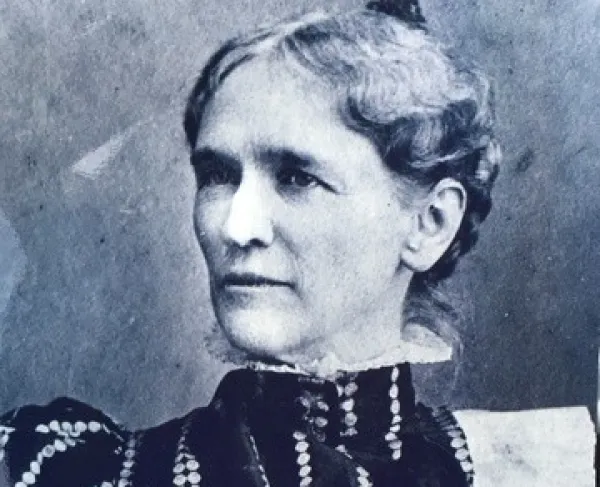

Patience L. Wright

A vegetarian, a Quaker, and America’s first professional sculptor was a woman known for her unconventional manners and strong opinions. Patience Lovell Wright was born in Oyster Bay, New York. At the age of four, the family moved to Bordentown, New Jersey, and, at sixteen, Wright moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to marry Joseph Wright. Wright maintained the home while Joseph Wright worked as a barrel-marker. She entertained her children throughout the day with sculptures she made from bread dough. Her sculpting skills came in handy when Joseph died in 1769, while Wright was pregnant with her fourth child. With the help of her sister Rachel Well, who had also recently widowed, the sisters turned their sculpting hobby into a profitable business.

Throughout colonial America, molding tinted wax was a popular art form. While it was considered “lower-class” than sculpting with bronze or stone, it was cheaper to manufacture and gave the sculptures a more “life-like” quality. Wright sculpted the hands and the faces of her sitters in wax, created a metal frame, attached the wax appendages, and dressed the wax/metal mannequin in clothes provided by the sitter. These sculptures and busts were life-size and fascinated the local population who visited her waxworks in Philadelphia and New York City.

After a fire claimed many of her original sculptures, Wright moved to London, England, and entered London society with the help of Jane Mecom, Benjamin Franklin’s younger sister. In London, Wright gained notoriety from her “rustic American manners.” She wore wooden shoes, skirted the lines of formality by kisses members of both sexes, and greeting individuals from all classes in the same manner. In a letter home to her family, Abigail Adams wrote that Wright’s manners were “overfamiliar” and that she had an overall lack of modesty becoming of a woman. Her wax sculpting technique scandalized many in London. Since wax needed to be heated to be molded, she manipulated the wax under her dress to utilize her body heat while the sitter was in the same room. Wright may have played up this gossip and scandal to encourage more people to visit her waxworks in the city and commission more works of art.

Even though she lived in England, Wright was a supporter of the American Revolution. As the war began, Wright wrote directly to John Dickinson, a Pennsylvania delegate to the First Continental Congress, about the British Army’s preparations in England. As the war continued, she gathered a coalition of pro-American activists in London to raise funds for American prisoners of war held in Britain and uncover information about British military strategy. She smuggled this sensitive information to the Continental Army by inserting pertinent information into wax figures she sent to the colonies.

Because of opposition to her overt pro-American sensibilities, Wright moved to Paris, France. For two years, she remained in France and, while there, created a wax model of Benjamin Franklin. She returned to England in 1782 and set her sights on returning to America in 1785. However, as she prepared for the long journey home, she suffered from a bad fall. On March 23, 1786, she died. While she provided crucial information to the Continental Army, the Continental Congress refused Wright’s sister’s plea for financial support for the burial. Wright’s gravesite is unknown to this day. Even though Wright created fifty-five life-size sculptures and numerous smaller wax pieces, only one sculpture remains. This lone sculpture depicting Lord Chatham (William Pitts) is displayed in Westminster Abbey in London, England. Regardless of her lack of recognition at the time of her death, Wright remains America’s first professional sculpture.