Considering Civil War Battlefield Monuments as Artworks

In the years and decades after the Civil War, thousands of monuments were raised on battlefields north and south (as well as in cemeteries, city parks and other locations) to honor specific individuals or, more generally, “those who served” — or, more hauntingly, “those who fell” — within a unit. Most of these monuments have little artistic interest. Even at Gettysburg, which unquestionably has the highest “artistic” quality of any Civil War sculpture garden, perhaps two-thirds of the monuments are simple obelisks or boxes that say little more than “this is where we were.” But there are monuments with considerable historic and artistic interest.

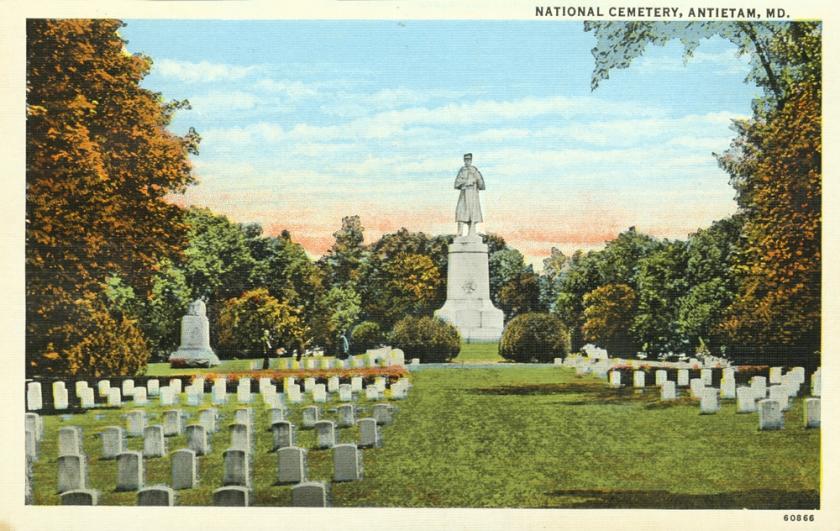

Monument building came in phases. During the war and in the first few years after, monuments tended to be simple stones that honored fallen soldiers. Then, as 25th anniversary events began to unfold (and as northern state legislatures began to make funds available), the veterans began taking note of their unit’s accomplishments. Starting in the 1890s and continuing for the next quarter century, veterans’ organizations and local governments put up equestrian statues of generals and large soldiers' and sailors’ monuments on battlefields, as well as in cities. Later still did the advent of mass production bring commemoration into the financial reach of small towns and villages, making the “infantryman” statue — all modeled on “Old Simon,” the huge private soldier at parade rest that stood at the entrance to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, before relocating to Antietam National Cemetery, where he remains —ubiquitous.

Also in the 1890s, Congress established the first national military parks at Chickamauga and Chattanooga, Gettysburg, Shiloh, Vicksburg and Antietam. War Department carriage roads made vast areas accessible for the first time. The prime monument-building period at Gettysburg had already passed by the time the park was officially formed, but there were major bursts of monument building activity at the other new parks. Large numbers of regimental or state monuments were erected at Vicksburg and Chickamauga–Chattanooga, with lesser but still significant numbers at Antietam and Shiloh, plus more than a handful at Manassas, Fredericksburg, Petersburg, and other locations.

But Gettysburg is unique in the number and in the artistic merit of the monuments erected there. The battlefield can boast of having on display examples from virtually all leading sculptors of monumental works during the late 19th and early 20th centuries — excepting Augustus Saint Gaudens, whose Civil War works include the famed 54th Massachusetts tribute in Boston and a statue of General Sherman in New York City.

Sculptors

The first of these was John Quincy Adams Ward, who designed the first “artistic” statue at Gettysburg, the standing portrait statue of Maj. Gen. John Reynolds (1871) in the National Cemetery. Ward set the template for portrait statues, with the subject holding a static but alert pose (many of the portrait statues at Gettysburg show the subject with clenched fists or an impatient or intense expression) and a fine level of detail, especially for military equipment such as binoculars, saddles, swords, etc. Ward’s major Civil War works elsewhere include the equestrian statue of Maj. Gen. George Thomas in Washington, D.C.’s Thomas Circle and the monument to the 7th New York State Militia in New York’s Central Park. He also covered Revolutionary War subjects, including the famous statue of George Washington on the porch of Federal Hall and the statue atop the Yorktown Victory Monument in Virginia.

Other well-known sculptors who worked at Gettysburg include James Kelly, who did one of the most prominent monuments on the field — the anxious Brig. Gen. John Buford staring intently down Chambersburg Pike, watching for approaching Confederates. Kelly also did a relief of George Washington praying at Valley Forge (in New York’s Federal Hall) and a relief of Barbara Fritchie at her grave site in Frederick, MD.

Caspar Buberl is officially credited with 10 Gettysburg monuments, more than any other sculptor. Most prominent are the New York Monument, which is modeled after Trajan’s Column in Rome and the jaunty skirmisher in the 111th New York monument. Other Gettysburg work includes the 5th, 6th, 9th and 10th New York Cavalry; the 41st, 52nd, 54th and 126th New York Infantry, and the monument to Smith’s battery, which occupies the most prominent position in Devils Den. Off the field, he created the 1,200-foot-long frieze on the exterior of the Pension Building — now operating as the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. — and numerous urban works in cities north and south.

Buberl’s crown, however, must be noted with an asterisk; a truly definitive count is impossible as several prominent granite companies (including Smith Granite Co., of Westerly, RI, Frederick and Field, and Hallowell) did not generally credit their artists. Robert D. Barr, staff sculptor for Smith Granite, is officially credited with four New York monuments at Gettysburg — the very prominent 40th New York, 78th & 102nd New York, 14th Brooklyn (84th New York)—and 15th New York Independent Battery Light Artillery — but undoubtedly did many more.

In the early years of the 20th century Henry Kirk Bush-Brown created two of the first three equestrian statues at Gettysburg, Maj Gen George Meade and Maj Gen John Reynolds. The pair are a study in contrasts: Meade and his horse both sit calmly, looking out over the approach of Pickett’s Charge, while Reynolds and his horse both are excited and alert as they look out over the July 1 field. The entire weight of the latter rests on two of the horse’s hooves, since the horse is posing with two hooves off the ground. Bush-Brown also created the Lincoln statue in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery and a third equestrian statue, for corps commander Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick. Elsewhere, he sculpted the version of “Mad” Anthony Wayne at Valley Forge.

J. Massey Rhind did portrait statues between 1915 and 1922 of four Gettysburg division commanders, as well as the National Grand Army of the Republic Memorial in Washington, D.C., and the national memorial to President William McKinley in Niles, Ohio. His works on other major battlefields includes the New York Peace Monument atop Lookout Mountain at Chattanooga.

Changing styles

The early monuments — at Gettysburg and its contemporary battlefield parks —were all designed in the traditional “monumental” or neo-classical style. Especially noteworthy are the Illinois Monument at Vicksburg, modeled on the Pantheon in Rome, the Georgia and Florida Monuments at Chickamauga and the Confederate Monument at Shiloh. Chattanooga has a number of impressive classical monuments: the New York Peace Monument and the Iowa Monument on Lookout Mountain, plus the Maryland, Illinois, New Jersey and New York State Monuments on Orchard Knob.

But this style was not universal and two early Gettysburg monuments are notable departures. The 86th New York monument (1888), features a plaque that is without a doubt the most “Victorian” monument at Gettysburg, showing a woman melodramatically praying over a fallen soldier with the legend “I yield him unto his country and his god.” A few hundred yards away stands the monument to the 99th Pennsylvania, which has a distinctly art deco “vibe,” despite its 1889 erection date.

In the 20th century, styles evolved away from the classical and to a more human-scale style. Examples include the portrait statue of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon who could be your next door neighbor striding forward casually (1988, Terry Jones); the Maryland monument (1994, Ron Tunison), which shows wounded Union and Confederate soldiers supporting each other, and the equestrian statue of Lee’s “Old Warhorse,” James Longstreet (1998, Gary Casteel), which is not only mounted on the ground but also shows the subjects in motion, as Longstreet turns to look toward a sound heard behind him.

A few monuments at Gettysburg were made in an explicitly modernistic style. The most famed sculptor to work at Gettysburg was Gutzon Borglum, best-known for his work on Mount Rushmore, but also behind the equally massive relief of Confederate figures in Stone Mountain, Ga. For the 1929 North Carolina Memorial, he created a tableau of soldiers lunging forward near the left flank of the Pickett-Pettigrew charge, a visual response to Virginia-centric portrayals of the assault.

The most explicitly modernistic sculptures at Gettysburg are the three pieces by Don DeLue, who is best known for his “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves,” the artistic centerpiece of the Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial, final resting place of 9,388 World War II casualties, largely from the aftermath of the D Day invasion. His three works at Gettysburg are the Soldiers and Sailors of the Confederacy Monument (1965), the Mississippi State Monument (1973) and the Louisiana State Monument (1971), which is most similar to the American Youth sculpture.

Showing emotion

Although most military monuments built in the 19th century showed little emotion, there were exceptions. Directly across Chambersburg Road from each other, the Buford statue anxiously watches approaching Confederate as he awaits the Army of the Potomac’s infantry, while the soldier of the 149th Pennsylvania (1888) stares with regret at the spot where the unit’s color guard was left behind in the confusion of its July 1 retreat. Another monument, to the 9th Pennsylvania Reserves (38th Pennsylvania, 1890) casts his head down in mourning.

Reconciliation

As monument construction hit its peak, a spirit of “reconciliation” was also sweeping the country. The speakers at many monument dedication ceremonies stressed “Our reunited country, stronger than ever, our former adversaries now our friends.” Some of the monuments included an explicit reconciliation theme in the monument itself. One Gettysburg example is the 66th New York (1889), bearing a bronze plaque has a banner that says “Peace and Unity” and shows a Union and a Confederate soldier shaking hands as the Yankee gives the Rebel a drink from his canteen.

Elsewhere, the New York Peace Monument at Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga also strikes an explicit “reconciliation” theme. Sculpted by Roland Hinton Perry, who at Gettysburg created portrait sculptures Union Brig. Gens. John Wadsworth and George Greene, the monument is surmounted by bronze figures of a Union and Confederate soldier shaking hands. Perry’s most notable non-Civil War sculpture is the Fountain of Neptune in front of the Library of Congress.

One monument that eschewed a reconciliationist approach was the Gettysburg monument of the 74th Pennsylvania, a regiment of recent German immigrants from Pittsburgh. The monument was modeled after a 2,000- year-old Roman sculpture, the Dying Gaul. In his dedication speech, former regimental commander Adolph von Hartung referred to the recent German victory over France and the monument built by the Germans to celebrate this victory.

Commemorative landscapes

Two planned commemorative landscapes at Gettysburg transcend a single monument to include a series of monuments and other features. These create an area with special meaning for millions of visitors.

Efforts to develop a national cemetery began almost the moment the armies left town, and plans for a Soldiers National Monument were approved in 1865. Completed four years later, the monument consists of four statues made of Italian marble. War is represented by an old soldier, telling his story to History, who records these deeds. The final two statues, Peace and Plenty, represent the crowning achievement of the soldier’s efforts. This tableau illustrates the prevailing national attitude: The war is over, the country is stronger than ever, and now we will grow. This manifested in the final conquest of the “Great American Desert;” the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad; an unprecedented period of urban, industrial, and population growth; and the beginnings of a world empire. The monument is the central feature of a large memorial complex. Civil War graves are arrayed (grouped by state) in a semi-circle, centered on the monument. Everything else at Gettysburg — the speech, the monuments, the reunions, the emergence as a national shrine — is the result of the cemetery’s development. The monument complex is the center of numerous events and commemorations, including the summertime “100 Nights of Taps,” several events where flags or wreaths are laid at the graves, the annual Dedication Day ceremonies on the anniversary of Lincoln’s speech, and the annual illumination.

The area known as The Angle is one of the most visited places on the battlefield and is considered by many the climax of the battle — even the “turning point” of the Civil War. This interpretation, and much of the physical infrastructure at this location, is a postwar invention by John Bachelder, self-appointed Gettysburg historian and early preservationist. He set out to promote this idea in his writings and speeches. Alone, Bachelder’s efforts were probably not enough to create the iconic landscape, but he got support from the Philadelphia Brigade association and the Pickett’s Division association, who started gathering on this spot in 1887 and posed the first “old veterans shaking hands across the stone wall” photos. This interpretation got a further boost when it became the scene chosen by painter Phillip Philippoteaux for his cyclorama paintings.

Other elements of the commemorative landscape include the Copse of Trees, the mid-lunge pose of the eye-catching soldier in the 72nd Pennsylvania Monument, the equestrian statue of Maj. Gen George Meade — locked in an eternal stare-down with Lee, directly across the field way — and markers for fallen heroes Alonzo Cushing and Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead. At the emotional center stands the massive open book known as the High Water Mark of the Rebellion Monument, designed by Bachelder to list the Confederate units that participated in Longstreet’s assault and the Union units that repulsed them. The sum of it all is that these few acres have become perhaps the most visited site on the battlefield and the favorite location for gatherings, commemorations, and reunions.

One last bit of artwork that deserves mention isn’t a sculpture. Until 1989, the site of Col. Charles Coster’s brief stand at Kuhn’s Brickyard late in the day July 1 was possibly the least evocative site on the battlefield, surrounded by houses and hemmed in by a roofing company warehouse. Then artist Mark Dunkelman painted a mural on the wall of the warehouse and converted it into arguably the most evocative site on the battlefield. It is the one place where the visitor has no need for imagination: the fight is right there in plain sight.