Standing Tall on Lake Erie

Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial, Put-in-Bay, Ohio

Just five miles south of the Canadian border, on an isthmus near downtown Put-in-Bay, Ohio, sits a 352-foot-tall monument towering over Lake Erie. Free-standing, Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial is the world’s tallest Doric column — a plain, thick column that is a common sight at federal buildings scattered throughout the nation’s capital. The monument stands 47 feet taller than the Statue of Liberty, that is, when measuring the New York Harbor landmark from the ground to the tip of Lady Liberty’s torch. A simple but striking presence, the structure — often referred to simply as Perry’s Monument — is also the only international peace memorial overseen by the National Park Service. However, it is representative of so much more than these pieces of sure-to-impress trivia.

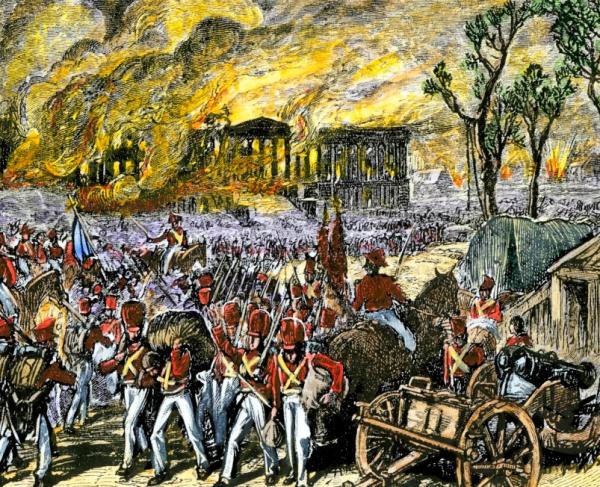

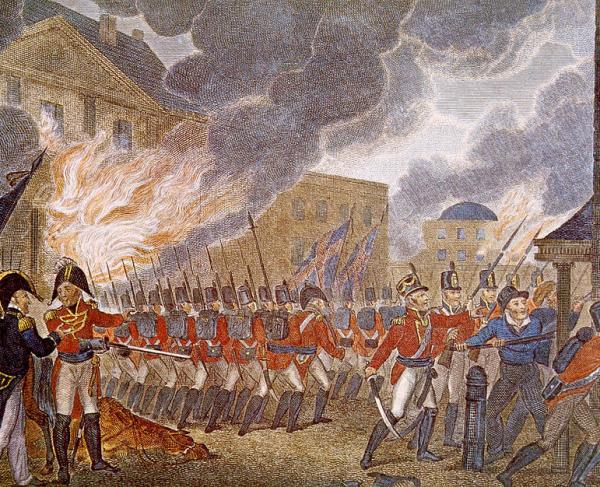

The monument’s construction started in 1915, the centennial of the War of 1812’s conclusion, with the intention to honor the brave souls who battled at the site 102 years prior.

The titular “Perry” is famed U.S. naval officer Oliver Hazard Perry, who, in February 1813, was sent to Erie, Pennsylvania, to complete the building of an American squadron that could hold its own against the powerful British Royal Navy in the Great Lakes region during the War of 1812. By early fall, his fleet was ready to engage.

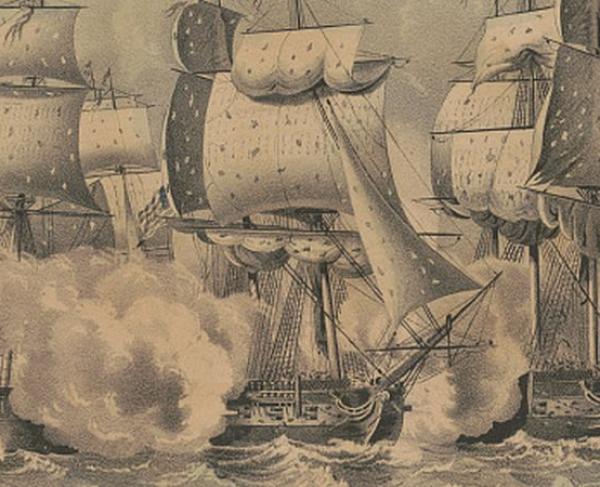

On the morning of September 10, 1813, a lookout aboard one of the American ships spotted six British vessels to the northwest of Put-in-Bay, beyond Rattlesnake Island. Word quickly spread to Master Commandant Perry, who issued orders to confront the British ships.

Since August 1812, the British Royal Navy had controlled Lake Erie. But, with Perry’s new fleet, the British were in store for an awakening. In July 1813, the British abandoned the Great Lake due to the new American threat, poor weather conditions and a shortage of supplies, as Perry’s fleet had severed the critical British supply route from Fort Malden to Port Dover. So, the Royal Navy attempted to break through Perry’s line.

While the British squadron was composed of six ships with 63 cannons, the American fleet was comprised of nine vessels and 54 guns. The British had superior guns for long-range firepower, while the Americans had the advantage in short-range guns, leaving Perry to pray for the wind to work to his benefit.

At 7:00 a.m., Perry ordered his two largest ships, USS Niagara and USS Lawrence, to set full sail and proceed directly toward the British line. But the Great Lakes’ notorious winds put up a long fight. Despite Perry’s wishes, the wind wouldn’t back his fleet. Nonetheless, at 10:00, just as he was readying to steer his ships away, the tricky wind suddenly shifted, situating itself directly behind the Americans.

Heading the British vessels was Commander Robert Heriot Barclay, an experienced Royal Navy officer from Scotland, who ordered his ships to go with the wind, taking the British vessels into battle.

The British ship Detroit crippled the American flagship Lawrence, forcing Perry to transfer his men to the Niagara. He made sure to bring his battle flag — emblazoned with the words “Don’t Give Up the Ship,” the dying words of friend James Lawrence, who had perished captaining his ship in the Atlantic conflict. And despite losing his flagship, Perry managed to disable and scatter most of the Royal vessels.

He received the British back onboard the tattered Lawrence to discuss terms of surrender — a deliberate move to force the British to confront the damage they had caused. After the battle, Perry dispatched a letter to General William Henry Harrison, saying, “We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner and one sloop.” Harrison, in turn, was then free to invade western upper Canada. Perry was hailed the “Hero of Lake Erie.”

Dedicated in 1931, Perry’s Victory and International Peace Memorial is a testimony of the American victory on Lake Erie and a nod to the long-standing peace among the U.S., Canada and Great Britain. Initially, three American and three British soldiers were buried at the monument as a reminder of the losses suffered by both sides during the fierce 1813 battle. The bodies were later exhumed and reburied in DeRivera Park.

There is no doubt that the towering structure embodies a history of great proportions.

Related Battles

123

440