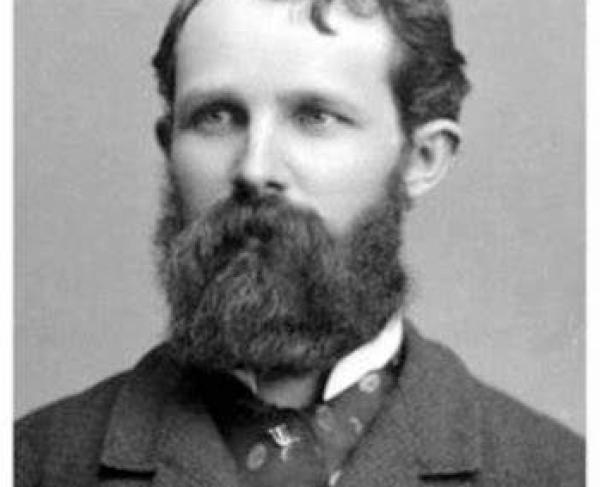

Preston Brooks

Among the most polarizing figures individuals in the decade before the American Civil War, Congressman Preston Smith Brooks took it upon himself to defend the slaveholding south through word and action. Brooks was born into a prominent family in Edgefield, South Carolina on August 5, 1819. He attended South Carolina College, where he impressed the faculty with his work but displayed a tendency for undisciplined behavior. After passing all his exams and awaiting graduation, Brooks heard a rumor that his brother had been mistreated by police. Preston rushed to the jail with brandished pistols and threatened the officers. Police calmed the incident, but university officials expelled Brooks. This tendency to react to perceived mistreatment and dishonor with physical violence characterized Brooks’s legacy. In 1840, Louis T. Wigfall engaged in a dispute with Preston’s elderly father, Whitfield Brooks. Preston challenged Wigfall to a duel on his father’s behalf and was wounded in the showdown. His injuries forced him to walk with a cane for the rest of his life.

Though he had not graduated college, Brooks nevertheless opened a law office and served as a representative to the South Carolina legislature in 1844. He also assumed the responsibilities of aide-de-camp to the governor. At the beginning of the Mexican War, Brooks organized an infantry company to join the Palmetto Regiment of South Carolina Volunteers and served as its captain. He returned home and sought to settle down and operate the large plantation he inherited. For half a decade he quietly thrived managing slave labor.

Brooks re-emerged in the political spotlight in 1853, after he was elected to represent South Carolina as a Democrat in the House of Representatives. Once in Congress, Brooks vehemently defended the southern right to own slaves and expand the institution into the territories. He supported the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which he claimed, “simply establishes the principle that the people, in their condition of Sovereign States, should be permitted to decide for themselves upon all matters affecting their internal government.” He listed slavery as the principal right he sought to protect and championed its existence in the same speech to the House of Representatives: “The institution of slavery, which is so fashionable now to decry, has been the greatest of blessing to this entire country.”

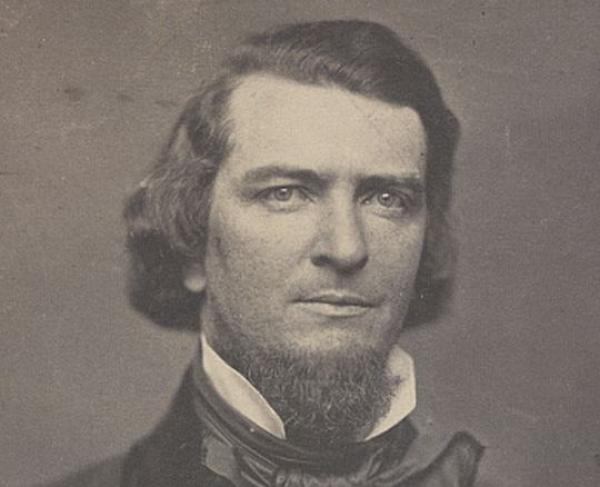

Abolitionists strongly opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and two years later they attributed the outbreak of violence in Kansas to the bill. Senator Charles Sumner produced the most scathing remarks in a speech he delivered to Congress for two days on May 19-20, 1856. Sumner specifically targeted South Carolina and its senator, Andrew P. Butler, who had co-authored the bill. Brooks fumed at Sumner’s castigation of both his home state and Butler, a distant relative. Two days later he viciously assaulted the Massachusetts senator, beating him his wooden cane. Brooks was arrested but only sentenced to a $300 fine. Enthusiastic supporters in his home district in South Carolina immediately provided the funds. A vote in the House to expel Brooks failed, but he nevertheless resigned voluntarily. This was a calculated move to demonstrate his support in the south, as his home district unanimously reelected him back to the vacated position.

Brooks enjoyed his newfound fame the rest of the year, receiving more invitations to events in his honor than he could attend. He would not, however, live to see the Civil War, the product of the violent sectionalism he encouraged. On January 27, 1857, he died of a sudden infection of croup that inflamed his throat. His body was returned to Edgefield, South Carolina, where a large gathering attended its burial. A eulogist of Brooks noted, “Perhaps no public man, in his day, attracted a larger share of attention… The object of the bitterest denunciation on the one side, and of the highest admiration on the other.”