Richard S. Ewell

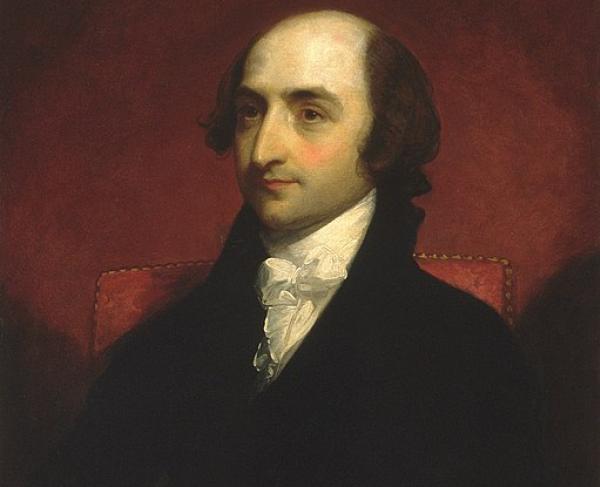

Richard Stoddert Ewell was born on February 8, 1817, in Georgetown in the District of Columbia. He was the grandson of Benjamin Stoddert, the first secretary of the navy, and of Revolutionary War Colonel Jesse Ewell. He grew up in nearby Prince William County on his family's estate Stone Lonesome.

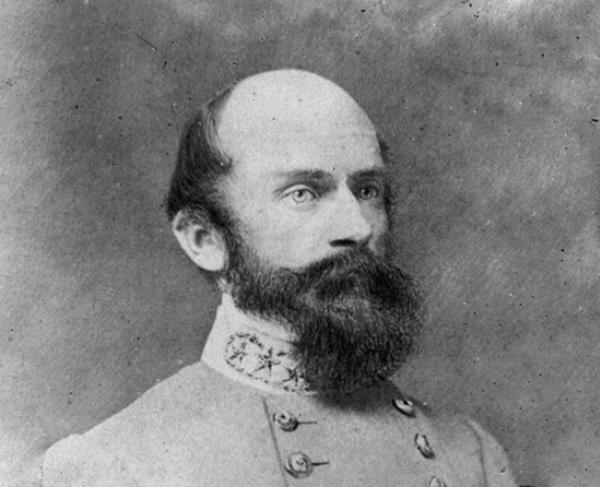

He attended the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he was known as "Old Bald Head" or "Baldy" to his friends. He graduated thirteenth in the Class of 1840. Soon after, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Dragoons. From 1843 to 1845, he served on escort duty on the Santa Fe and Oregon trails, being promoted to first lieutenant in 1845.

Ewell served in the Mexican-American War under General Winfield Scott. He was promoted to captain for his bravery at Contreras and Churubusco. Afterwards, he explored the New Mexico Territory after it was ceded by Mexico. He was wounded in a skirmish with Apaches in 1859, and in 1860, he was sent home from Arizona to recover from an illness. Injury and illness would plague his time in the Civil War.

The secession of Virginia prompted Ewell to resign his commission in the U.S. Army, although he had been pro-Union up until this point. On May 7, 1861, he resigned and then joined the Virginia Provisional Army, being named colonel two days later. In a skirmish at Fairfax Court House on May 31, he was wounded, giving him the distinction of the first field-grade officer to be wounded in the Civil War.

Ewell then received a commission as a brigadier general on June 17, 1861. He commanded a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run but saw little combat. On January 24, 1862, he was promoted to major general and served alongside General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson through the Valley Campaign in Virginia. He protected Richmond during Union General George McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign, and commanded his troops successfully at the battles of Malvern Hill, Gaines’ Mill, the Seven Days Battles, and the Second Battle of Bull Run. At the Battle of Groveton, Ewell was severely wounded in the leg, which was amputated below the knee. After several months of recovery, Ewell returned to the army and participated in the Battle of Chancellorsville. On May 23, 1863, Ewell was promoted to lieutenant general to replace General Jackson, who had been mortally wounded at Chancellorsville. He served with distinction at the Second Battle of Winchester, capturing a large Federal force and supplies.

Afterward, however, his military reputation began to declines sharply. During the Battle of Gettysburg, he led his men well in the early portions of the battle on July 1. However, when General Robert E. Lee ordered him to assault Union positions on Cemetery Hill "if practicable," Ewell declined to do so, providing Union troops crucial time to reorganize and fortify their positions. There is much controversy about why Ewell decided not to attack on the evening of July 1, but nonetheless, many of his fellow generals blamed him for the loss at Gettysburg.

Following the Gettysburg Campaign, Ewell performed well during the Battle of the Wilderness, but again received criticism for his inaction and indecisiveness at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. Following the battle, Ewell, who was suffering from health problems, was relieved of commanding his division, and sent to command the defenses of Richmond. During the retreat from Richmond, Ewell and his men were surrounded and captured at Sailor's Creek on April 6, 1865. He remained imprisoned at Fort Warren for the remainder of the war, where he and sixteen other former generals penned a letter to General Ulysses S. Grant condemning the assassination of Abraham Lincoln.

After the war, Ewell became a "gentleman farmer" at his wife Lizinka's estate in Spring Hill, Tennessee. He had known her since he was a teenager, but only married her after the time she spent tending to him after his amputation rekindled their romance in 1863. He also leased a successful cotton plantation in Mississippi. He was active in his local community, serving as president of the Columbia Female Academy's Board of Trustees, in St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Columbia, and as president of the Maury County Agricultural Society. Throughout the rest of his life, he continued to suffer from various ailments. He and his wife died from pneumonia, three days apart, in 1872, and were buried together in Nashville.