Sarah Morgan Dawson

On January 10, 1862, in the first entry of her new diary, Sarah Morgan wrote “A new year has opened to me while my thoughts are still wrapped up in the last; Heaven send it may be a happier one than 1862.” The year prior her father had passed away unexpectedly, her brother Henry Waller Fowler Morgan had been killed in the duel, and the Civil War had just begun. Her wish did not come true.

Nineteen years prior, Sarah Morgan was born to Judge Thomas Gibbes Morgan and his second wife Sarah Fowler Morgan in New Orleans, Louisiana. Both parents were not native to the South. Thomas “Gibbes” Morgan, a New Jersey-born and Pennsylvania educated lawyer, had immigrated to the South in the 1820s with his brother Morris Morgan. His brother married a daughter of Colonel Philip Hicky and became a respected member of the planter class. Thomas, in contrast, became a successful lawyer and public servant. Sarah, his wife, was born in New England. Orphaned at a young age, she grew up with her guardian George Mather on his large Louisiana plantation. While she did not inherit the plantation, she did inherit the ideology of the planter class and a high-class status in southern Louisiana. Sarah Morgan, the seventh child of the pair, grew up in a wealthy established household amongst the New Orleans elite.

While she was amongst the elite, her role was one of future wife and mother. She was formally educated for less than a year and privately educated by her mother and sisters. Throughout her diaries she notes books on a variety of topics she read and educates herself but does not comment heavily on economical and political topics in her diaries. Her father, while firmly invested in the South, originally wanted the Union to remain together. However, once South Carolina secedes from the Union in December 1860, her father supported the Confederacy. Sarah followed his lead.

During the outbreak of the Civil War, Sarah lived with her mother and several sisters in their Baton Rouge home. Her brothers Thomas “Gibbes” Jr. and George resigned their United Stated Army positions in order to serve in the Confederacy. James Morris, another brother, was enrolled in the United States Naval Academy and resigned his spot in order to join the Confederacy. Sarah lived in relative comfort and isolation in New Orleans for the beginning of the war. This isolation disappeared when Captain Farragut overtook New Orleans on April 25, 1862, several months after her first diary entry. The family fled to Linwood, an estate 20 miles from Baton Rouge, because they were worried about their own city’s capture. Their predications came true when Baton Rouge was taken by the Union on August 5, 1862. When Port Hudson, which was miles from Linwood, became the site of military hostilities in March 1863, the family once again fled. This time the travelled to Lake Pontchartrain and then into Union occupied New Orleans, where they remained for the rest of the war.

Both family homes in Baton Rouge and New Orleans were ransacked by Union soldier. Much of the family’s wealth disappeared during the war and, in later diary entries, Sarah began to worry about earning a living. In 1864, the family learned that both Thomas “Gibbes” Jr. and George had died of disease in a Confederate camp. James Morris returned from his enlistment after the war’s conclusion.

After the war, Sarah began writing for the newspaper News and Courier. She wrote female-centric pieces about marriage and education. While there she met and was courted by Francis Warrington Dawson, the owner of the newspaper and former Confederate soldier. On January 27, 1874, they married. The couple had three children, two of which lived to adulthood. After her husband’s premature death in 1889, she began writing again to earn a living. Eventually, she followed her son Francis Warrington Dawson Jr. to Paris.

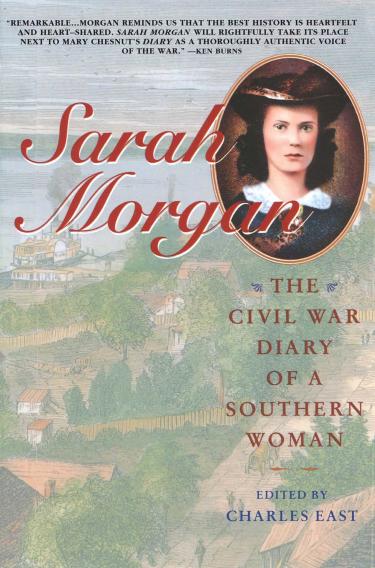

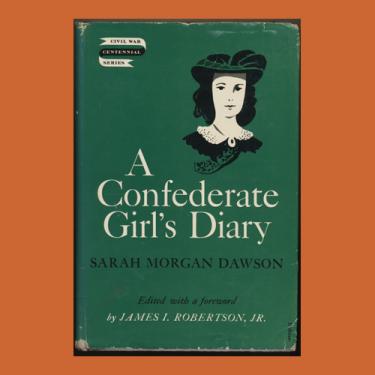

Throughout the course of the war, Sarah wrote five diaries. The first started on January 10, 1862 and the last ends on June 15, 1865. Originally, her diary collection contained a sixth book detailing her travels to her brother James’s wedding to Helen Trenholm in South Carolina via New York. During her life, she told her son to destroy all the diaries. However, while she was living in Paris, he convinced her to keep the diaries and allow him to publish them. She consented. After her death in 1909, James Jr. worked on edited her diaries into the book A Confederate Girl’s Diary. It was published in 1913. It was reedited and published again, two years before his death, in 1960. Historian Charles East took an interest in Sarah again in the 1980s and reedited and republished her diaries in 1991 under the title Sarah Morgan: The Civil War Diary of a Southern Woman with diary entries that Dawson Jr. had originally omitted and a forward detailing her life

Sarah Morgan’s diary describes the events of the Civil War witnessed by and understood through the eyes of a nineteen-year-old girl. Her diary joins the testimonies and diaries of others during the war, such as Mary Chesnut’s published diary. However, unlike Mary Chesnut, who was twenty years older and more political, Sarah Morgan captures the emotion and sometimes contradictory feelings of young woman during the war. While she was of the upper middle class, and understands the world through a lens of privileges, she still faces the hardships and uncertainties of the Civil War. Because of her gender, she cannot fight on the battlefields to support the Confederacy. However, she has an art of eloquence and a manner of storytelling that makes the Civil War tangible for future audiences. Her eloquence has allowed the book to continue circulating today.