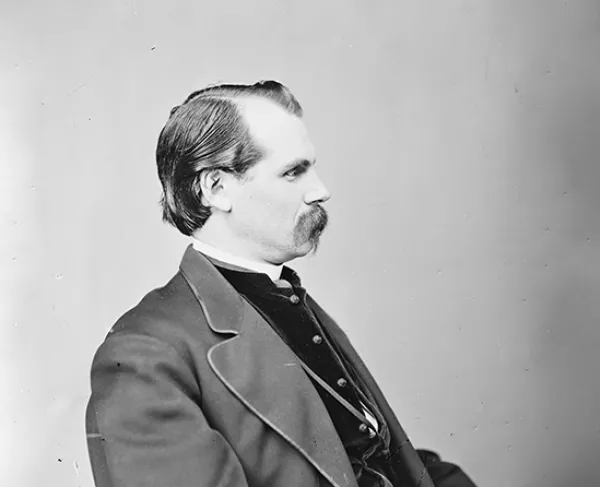

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe

Thaddeus Sobieski Constantine Lowe was born August 20, 1832 in Jefferson Mills, New Hampshire. Intellectually curious and driven from a young age, Lowe had almost no formal education but demonstrated an appetite for learning which hinted at his future career as an inventor. At the age of 18 he attended a lecture on the subject of lighter-than-air gases and so impressed the professor, Reginald Dinkelhoff, with his enthusiasm that Dinkelhoff offered to take the young Lowe on the lecture circuit with him as an assistant. Over the course of the next decade, Lowe devoted himself to balloon aviation, and became a prominent builder of balloons and showman. In 1855, at one of his demonstrations, he met the Parisian actress Leontine Augustine Gaschon, and they were wed just one week later. The couple eventually had ten children. In the latter part of the decade he set about building bigger balloons, with an eye towards a transatlantic crossing, and began to garner a prominent scientific reputation. In April, 1861, Lowe intended to make a test run from Cincinnati, Ohio to Washington, D.C. He took off on April 19, just a week after the fall of Fort Sumter, but instead of heading due east towards Washington Lowe’s balloon was blown way off course, eventually landing in Unionville, South Carolina. There, he was arrested on suspicion of being a Northern spy. When he finally convinced the Confederate authorities of his innocence he returned to Cincinnati, only to be immediately summoned to Washington. The government was in fact interested in his experimental balloons as a means of gathering intelligence.

In June of 1861, Lowe demonstrated for President Lincoln how useful his balloons could be when combined with new electric telegraph technology. On the 16th of that month, from a height of 500 feet above the National Mall in Washington D.C., Lowe transmitted to the President: “This point of observation commands an extent of country nearly 50 miles in diameter. The city with its girdle of encampments, presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station, and in acknowledging indebtedness for your encouragement for the opportunity of demonstrating the availability of the science of aeronautics in the military service of the country.” Little more than a month later, Lowe and his balloon were in action during the First Battle of Bull Run, after which Lincoln approved the formation of the Union Army Balloon Corps, with Lowe as Chief Aeronaut (at a colonel’s salary). Lowe’s principal contribution to the militarization of balloon technology, and its use in the field, was the portable hydrogen gas generator, which allowed the balloons to accompany the army wherever they were needed. Made of a rugged material that could withstand the wear and tear of active campaigning, Lowe’s balloons could also be inflated in a very short amount of time. They were a sensation in Washington, and many prominent military and political figures accompanied him on his ascensions. He eventually built a total of seven balloons and twelve generators for the war effort.

In the spring of 1862, Lowe and his balloons played a significant role in the Peninsula Campaign, observing the enemy’s defensive dispositions and helping relay information during the slow but steady advance on Richmond. At the Battle of Seven Pines, Lowe’s aerial reconnaissance helped identify the buildup of Confederate forces near the Fair Oaks train station prior to the start of the battle. In addition to providing valuable aerial reconnaissance information, Lowe, when supported with direct telegraphic links to commanders, was able to provide near real-time artillery spotting to Army of the Potomac artillery units. While operating from Dr. Gaines’ farm on the future Gaines’ Mill battlefield, Lowe was positioned close enough to Richmond that he could clearly see the movements of soldiers and individuals within the city. The sight of Lowe’s balloons, ominously hanging over the Virginia landscape, certainly must have unsettled the Confederates, who knew their movements were being observed by the enemy. While several attempts were made to destroy the Union balloons via long range artillery fire, none of Lowe’s balloons were ever damaged or destroyed in combat. Though Lowe and his balloons were able to avoid damaging enemy fire, Lowe himself contracted a serious bout of malaria from the mosquito infested waters near the Chickahominy River.

After the conclusion of the Peninsula Campaign, Lowe’s Balloon Corps was utilized during the 1862 Fredericksburg and 1863 Chancellorsville campaigns. During this period, some Union commanders and leaders began to question Lowe’s heavy expenditures and poor administrative skills. Placed under a more controlling military command structure, the frustrated and sick Lowe resigned from his balloon corps and the use of balloons within the Union armies ended shortly afterwards.

Lowe returned to the private sector following the war, and made a fortune developing ice-making machines before moving to Los Angeles, California in 1887. He died at his daughter’s home in Pasadena in 1913, aged 80.