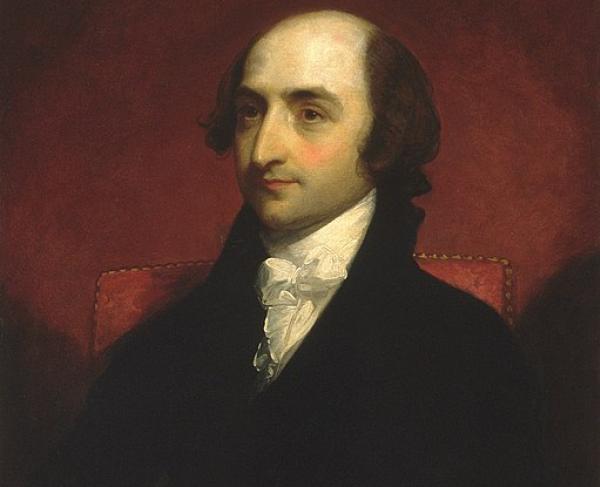

W.H.F. “Rooney” Lee

Born at Arlington in 1837, William Henry Fitzhugh Lee was the second son of Robert E. Lee and Mary Anna Randolph Custis. His pedigree included “Light-Horse” Harry Lee and Martha Washington. Though hardly the most famous member of his family, “Rooney”—as he was known—nevertheless played an important part in the nation’s most trying ordeal.

After spending most of his childhood moving from post to post with his father, Lee was granted admission to Harvard in 1854, where his record was less than exemplary. It was hardly surprising that in 1857 Lee left the school to accept a commission in the army as a second lieutenant. Assigned to the 6th Infantry under Albert Sidney Johnston, the young officer was sent to Utah Territory to quell the Mormon Rebellion. Following additional assignments in Texas and the Pacific Northwest, Lee resigned his commission in 1859 to take up farming at the White House estate on the Pamunkey River in Virginia.

Lee’s simple agrarian life, however, was short-lived. When his home state seceded in April 1861, the Virginian once again took up the sword—this time as a captain in the 9th Virginia Cavalry, attached to what would ultimately become his father’s command, the Army of Northern Virginia. In his year of service with the regiment, Lee took an active part in the Seven Days’ Battles, and the Second Manassas and Maryland Campaigns, ascending to the colonelcy of the regiment along the way. When the Army of Northern Virginia reorganized its mounted arm in November 1862, “Rooney” Lee was given charge of a brigade and promoted to brigadier general.

Limited cavalry operations at the end of 1862 and in the spring of 1863 gave Lee little chance to test his mettle as a brigadier. However, on the morning of June 9, 1863, Lee, then camped near Brandy Station, Virginia, heard firing in the direction of the Rappahannock River at Beverly’s Ford. Riding to the sound of the guns, the general organized a defensive position, taking advantage of the terrain and a low stone wall. For five hours Lee’s cavaliers fought off repeated assaults by Union cavalry under General John Buford, effectively stalling the Federal advance and exacting a fearsome toll in casualties. Lee, however, did not escape unscathed. As the battle of Brandy Station drew to a close, the brigadier was badly wounded in the leg.

The general’s wound required several months of convalescence, during which he was captured. The next nine months of Lee’s career were spent as a prisoner at Forts Monroe and Lafayette. In December of 1863, Lee learned of the death of his wife. He was exchanged in March of 1864.

When Lee returned to the army that spring, he was given command of a division and promoted to major general, making him the youngest Confederate officer to hold that rank. He rendered reliable service during the war’s final year, most notably at the April 1865 battle of Five Forks. While his fellow generals George Pickett, Thomas Rosser and (his cousin) Fitzhugh Lee, enjoyed their lunch, Rooney defended against a combined assault by infantry and cavalry and, despite his best efforts, was ultimately overwhelmed. Little more than a week later, Lee surrendered his cavalry along with the entire remnant of his army at Appomattox Court House.

After the war, Rooney Lee resumed his life as a farmer and was the president of the Virginia State Agricultural society for several years. He was eventually drawn back into public life, serving a term as a state senator from 1875 to 1879 and later as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1887 to 1891. W. H. F. Lee passed away shortly after the expiration of his term and was buried in Alexandria. In 1922 his remains were reinterred at the Lee Mausoleum in Lexington, Virginia.