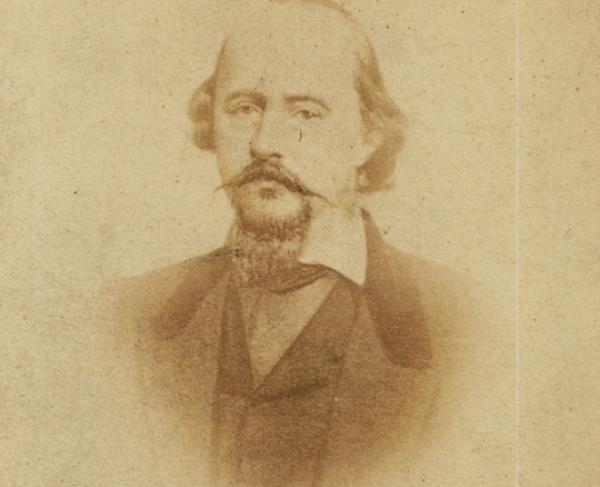

William W. Loring

A man whose military career spanned more than four decades and three different flags, William Wing Loring was born in Wilmington, North Carolina, on December 4, 1818. His father Reuben hailed from Massachusetts and could trace his ancestry back to the original Plymouth Colony, while his mother Hannah came from a prominent North Carolina family. The family relocated to St. Augustine, Florida, which had been recently ceded by Spain to the United States.

His military career began at age 14 when he volunteered with the 2nd Florida Volunteers in a war against the Seminole Indians. At age 17, upon hearing news of the loss of the Alamo, young Loring ran away to join the Texas revolutionaries in their fight against Mexico. His father followed him to Texas and forced him to return to Florida. But once he had returned, Loring rejoined the military effort against the Seminoles, distinguishing himself and getting promoted to 2nd lieutenant by 18.

In 1837, he was sent to the prestigious Alexandria Boarding School, before briefly attending Georgetown College. He returned to Florida to work in a law office, being admitted to the bar in 1842 and serving in St. Augustine. He served in the Florida House of Representatives from 1843 to 1845 and launched an unsuccessful bid for State Senate.

At the outbreak of the Mexican-American War, Loring jumped at the opportunity to once again take up arms against Mexico, joining the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen. He participated in many of the decisive engagements of the conflict. He lost his arm leading the assault on Belan Gate at Mexico City, one of the last battles of the war. He was promoted to brevet colonel for his gallant actions.

With the war over, Loring decided not to return to his law office and instead remained in the army. He took part in a dangerous expedition from Missouri to Oregon, as well as other missions that helped the U.S. expand westward. He also traveled to Europe to study military tactics. Upon his return, in 1861, he was named commander of the Department of New Mexico. But on May 1, he resigned his commission to join the Confederate Army. He traveled to Richmond, where he was promoted to brigadier general, and General Robert E. Lee assigned him to the Army of Northwestern Virginia and sent him to stop Union General George B. McClellan’s advance into the region. Loring was plagued by supply problems, bad weather, and disease spreading among his men during the operation, hindering his ability to win against the Federals. Lee himself was sent to take charge of the region, and although his efforts against the Federals ended no better than Loring’s, Lee was left with serious misgivings about Loring’s ability as a commander. His men had a more favorable view of him, and he earned a slew of nicknames, including “Old One Wing,” “Old Ringlets,” and “Old Billy.”

In late 1861, Loring’s army was sent to assist General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s campaign in the Shenandoah Valley. Loring immediately came into conflict with Jackson, who demanded blind obedience and refused to disclose his plans to Loring. During the winter, Loring’s men were forced to weather the cold and wet conditions at Romney while Jackson’s men had better conditions at Winchester; with his troops on the verge of mutiny, Loring petitioned Richmond to get his men sent to Winchester. Jackson was angered by this, feeling his authority had been undermined and brought charges of insubordination against Loring. The Confederate government didn’t want to alienate either commander, especially so early in the conflict, so Loring was promoted to major general and reassigned to southeastern Virginia. Despite this, Jackson’s and Lee’s enmity against him, and the fact he was not a professional soldier trained at West Point, all but guaranteed he would see little glory in the major battles of the war.

Loring spent a few months at Norfolk in early 1862, where he caught pneumonia that kept him out of action for more than a month. He saw naval action aboard the CSS Virginia as it tried to provoke the USS Monitor into battle. After retreating from Norfolk, he was moved to the Department of Southwestern Virginia to guard the back door of Richmond during McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. After the danger had been assuaged, Loring operated successfully in the Kanawha Valley in what is now West Virginia. Lee wanted him for his invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania in the late summer of 1862, but Richmond ordered him to stay. Loring then resigned over a conflict over recruiting practices in Virginia, but soon sought reassignment. However, when told of this, Lee supposedly coldly responded, “There is no room in this army for that man.”

His military career in Virginia at an end, Loring was sent to defend Vicksburg. In his defense of Fort Pemberton against the Federal flotilla on the Mississippi River, he earned the nickname “Old Blizzards” when he urged his men to “Give them blizzards, boys, give them blizzards!” Loring had little respect for Confederate General John C. Pemberton, whom he openly ridiculed. At the Battle of Champion Hill, Loring’s division got separated from the mass of Pemberton’s army retreated back into the city; but instead of reuniting with him, Loring took his men to unite with General Joseph E. Johnston.

Loring then was assigned to the Army of Mississippi under General Leonidas Polk, fighting Union General William T. Sherman as he advanced into Georgia. When Polk was killed, Loring assumed command of the army and played a large role in defeating Sherman at Kennesaw Mountain. However, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed someone else in his stead, which “deeply chagrined” him. At Ezra Church, Loring was shot in the chest and was out of action for more than a month as he recovered. By that time, Atlanta was under siege, and he served tearing up railroads to draw Sherman away from Atlanta, which proved unsuccessful.

After the fall of Atlanta, Loring, now under General John B. Hood, marched to Tennessee, hoping once again to provoke Sherman into a chase. But instead, they were defeated decisively at Franklin, and effectively eliminated at Nashville. Hood’s army desperately retreated to Alabama when Loring was sent to North Carolina to serve under Johnston once again. He fought in that army’s final offensive at Bentonville, which ended in failure and retreat. He was present at the surrender at Bennett Place on April 26, 1865.

With the war over, Loring moved to New York City to pursue banking. Soon after, however, his old enemy Sherman recommended him to Egypt to modernize their army to assert its independence from European powers. Loring agreed and quickly won the favor of Ismail, the Khedive. He was in charge of the country’s coastal defenses for a time. However, he and the other Americans fell out of favor when Egyptian forces were repeatedly defeated by Ethiopia and were soon dismissed. However, Loring was now a decorated Egyptian officer, earning the title of “Fereck Pasha” or major general.

Loring returned to Florida in 1880 and unsuccessfully ran for Senate. He then returned to New York, while also traveling between the West, Chicago, and St. Augustine, where he owned a small orange grove. He wrote a book about his experiences in Egypt entitled A Confederate Soldier in Egypt, which made him the foremost American authority on all things Egypt. He died in New York in 1886 in the midst of working on his memoirs.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...

Related Battles

2,457

3,840

2,326

6,252

1,527

2,606