Atlanta

Fulton County, GA | Jul 22, 1864

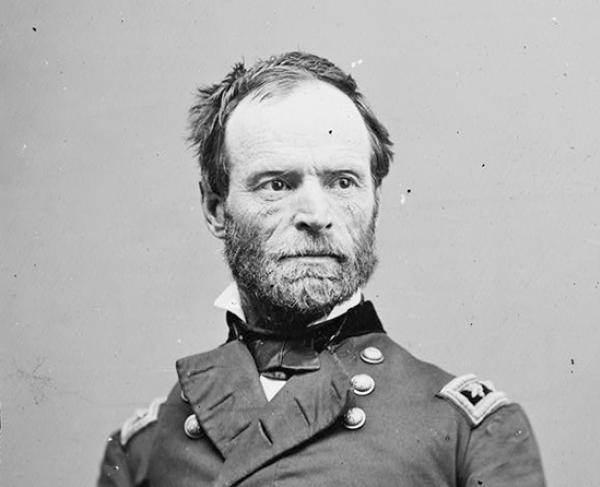

The Union victory in the largest battle of the Atlanta Campaign led to the capture of that critical Confederate city and opened the door for Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s most famous operation—the March to the Sea and the capture of Savannah.

How it ended

Union victory. Confederate Lt. Gen. John B. Hood’s attack on Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s troops at Atlanta was repulsed with heavy losses. Hood and Sherman continued to battle for the crucial Confederate city throughout the summer until Hood was finally forced to abandon Atlanta to Union forces on September 1, 1864.

In context

In the spring of 1864, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, general-in-chief of all U.S. armies, ordered five, simultaneous offensives to press Confederates all along their frontier. Grant recognized that the Confederates could not win a war of attrition, and he instilled in his commanders the need to exhaust the resources of the Rebels by destroying their armies.

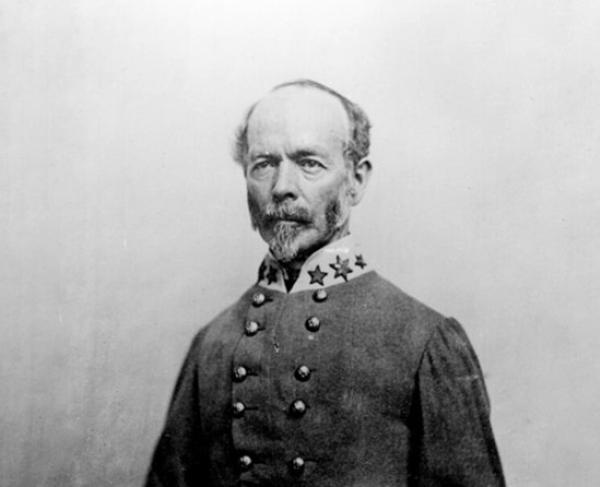

Grant assigned his friend Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman to command the fifth advance against Gen. Joseph E. Johnston’s army. Johnston was charged with defending Atlanta, the largest industrial, logistical, and administrative center outside of Richmond. Atlanta was at the junction of four railroads that connected all remaining Confederate-held territory east of the Mississippi River.

By early July, Johnston had fallen back into the defenses of Atlanta. Frustrated by Johnston’s lack of aggressiveness, President Jefferson Davis replaced him with Lt. Gen. John B. Hood on July 18. Within days, Hood launched two attacks on Sherman—one at Peach Tree Creek on July 20 and the other along the Georgia Railroad (known as the Battle of Atlanta) on July 22. Both ended in defeat and led to the fall of Atlanta in September. The capture of such a valuable Confederate stronghold boosted Northern morale, helped ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln in November, and precipitated the downfall of the Confederacy.

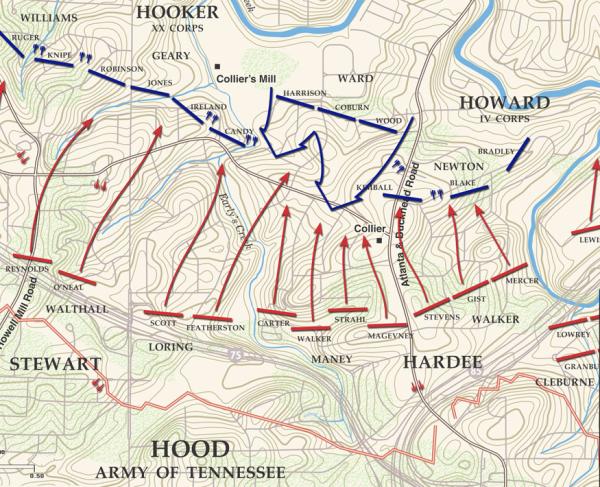

On July 21, 1864, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s three armies are separated on the outskirts of Atlanta. Major General James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, facing Atlanta from the east astride the Georgia Railroad, has its left flank “in the air” (Sherman has sent his cavalry to wreck the railroad further east). This situation presents Confederate general Hood with an opportunity to launch a flank attack like the one made famous by “Stonewall” Jackson at Chancellorsville.

Hood plans for the corps of Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee to drop back from its lines north of the city into the main fortified perimeter on the night of July 21–22; the remaining corps of Maj. Gen. Alexander P. Stewart and Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Cheatham will follow. Hardee’s corps will march through and out of the city, southeast then northeast, guided by Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry, and jump into McPherson’s left-rear, while Wheeler attacks McPherson’s wagon trains at Decatur. Cheatham will support Hardee from the east edge of Atlanta. It is an ambitious plan, calling for a 15-mile night march by Hardee’s troops and a dawn attack on July 22.

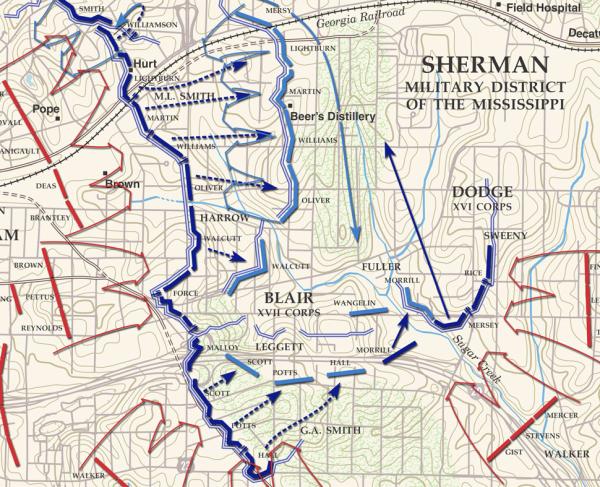

July 22. A late start, exhausted troops, a hot night, and dusty roads combine to bring the four assault divisions not nearly far enough into McPherson’s rear when Hardee, well behind schedule, decides to deploy. Then rough terrain adds further delay, and Confederate Maj. Gen. W. H. T. Walker is killed while getting his division into place. Hardee’s “surprise” attack does not begin until shortly after noon.

The Federals have better luck. By chance, a Union Sixteenth Corps division under Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Sweeny happens to be in just the right position to meet Hardee’s opening assault. Instead of overrunning hospital tents and wagon trains in McPherson’s rear, Walker’s and Maj. Gen. William Bate’s troops run face-to-face into veteran Yankee infantry.

McPherson, having left Sherman’s headquarters just before the firing started, is watching Sweeny contend with the Rebels. He rides off to see how Maj. Gen. Frank Blair’s Seventeenth Corps are faring; by now it has been struck by Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s hard-hitting division. McPherson and his staff are riding down a wagon road when they unexpectedly run into part of Cleburne’s line. “He came upon us suddenly,” Capt. Richard Beard of the Fifth Confederate Infantry later remembered:

I threw up my sword as a signal for him to surrender. He checked his horse, raised his hat in salute, wheeled to the right and dashed off to the rear in a gallop. Corporal Coleman, standing near me, was ordered to fire, and it was his shot that brought General McPherson down.

McPherson’s subordinates dash off. One Union officer strikes a tree in his flight; the blow smashes his pocket watch and preserves the time of the general’s death—2:02 p.m.

Cleburne’s attack initially overruns part of the Union line, capturing two guns and several hundred prisoners. Then the Southerners run up against infantry and artillery on a treeless hilltop occupied by Brig. Gen. Mortimer Leggett’s division and are stopped cold. Brig. Gen. George Maney’s Confederate division joins in the fight, but Leggett holds onto his hill.

Around 3:00 p.m., Hood orders Cheatham’s corps to launch an attack from Atlanta’s eastern line of works. Cheatham’s fierce but uncoordinated assaults against the Federal line held by Logan’s Fifteenth Corps meet with initial success, overrunning the Union line at the Troup Hurt House and capturing artillery, until a counterattack forces it back. At the end of the afternoon, the Confederates retire back to their initial positions. The Battle of Atlanta, the bloodiest of Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, is over.

3,722

5,500

Hood’s effort to roll up Sherman’s left flank fails. On July 27, Sherman resumes operations against the city by shifting to the west side to cut the Macon & Western Railroad. The armies meet again at Ezra Church on July 28, which earns the Union another victory. Worn out after that, both armies settle in for a siege of the city that lasts throughout August.

News of Union general James McPherson’s death elicited sincere expressions of grief from both Union and Confederate soldiers, many of whom had been classmates of his at West Point long before the Civil War. McPherson, a skilled army engineer and accomplished officer, proved his mettle at Fort Donelson and Shiloh. He was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General of Volunteers in May 1862 and to Major General of Volunteers on October 8, 1862. In December 1862, McPherson assumed command of the Seventeenth Corps of the Army of the Tennessee and participated in Grant's assault on Vicksburg. He became the commanding general of the Army of the Tennessee, which assisted General William T. Sherman in his efforts to capture Atlanta, in March 1864.

When notifying Union military authorities of McPherson's death, a shaken William T. Sherman wrote:

Not his the loss; but the country and the army will mourn his death and cherish his memory, as that of one who, though comparatively young, had risen by his merit and ability to the command of one of the best armies which the nation had called into existence to vindicate its honor and integrity.

History tells us of but few who so blended the grace and gentleness of the friend with the dignity, courage, faith, and manliness of the soldier.

His public enemies, even the men who directed the fatal shot, never spoke or wrote of him without expressions of marked respect; those whom he commanded loved him even to idolatry; and I, his associate and commander, fail in words adequate to express my opinion of his great worth.

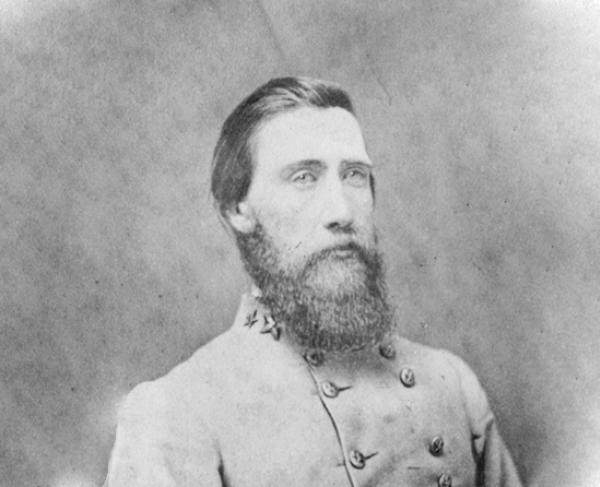

Confederate general Hood, who had attended West Point with McPherson, expressed heartfelt grief for an opponent who was also a friend:

I will record the death of my classmate and boyhood friend, General James B. McPherson, the announcement of which caused me sincere sorrow. Since we had graduated in 1853, and had each been ordered off on duty in different directions, it has not been our fortune to meet. Neither the years nor the difference of sentiment that had led us to range ourselves on opposite sides in the war had lessened my friendship; indeed the attachment formed in early youth was strengthened by my admiration and gratitude for his conduct toward our people in the vicinity of Vicksburg. His considerate and kind treatment of them stood in bright contrast to the course pursued by many Federal officers.

The words of Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant, who corresponded with McPherson’s grandmother, serves as both a eulogy and reminder of the true price of war.

A nation grieves at the loss of one so dear to our nation's cause. It is a selfish grief, because the nation had more to expect from him than of almost any one living. I join in this selfish grief, and add the grief of personal love for departed. He formed, for some time, one of my military family. I knew him well; to know him was to love…. Your bereavement is great, but can not exceed mine.

Even before the Atlanta Campaign, Davis thought Johnston was too cautious a general. Johnston entered the Civil War as one of the South’s senior officers. He had an early victory at the First Battle of Bull Run (Manassas) in July 1861, and while his performance earned him a promotion to full general, it also set off a feud with Davis, who criticized him for not pursuing the retreating Union Army. But Johnston was equally displeased with the Confederate president. After learning that his promotion to full general still placed him below other officers, including Robert E. Lee, Johnston felt personally insulted.

The relationship between the two men continued to decline. During the Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862, in which Union general George B. McClellan attempted to move on Richmond, Johnston elected to withdraw from the Virginia Peninsula in the campaign’s early stages, angering Davis. After making a defensive stand at the Battle of Williamsburg, the general continued to retreat. Under continued pressure from Davis, Johnston finally attacked McClellan at the Battle of Seven Pines on May 31, 1862. The offensive succeeded in blocking the Union advance, but Johnston was severely wounded in the fight. During Johnston’s convalescence, his replacement, Robert E. Lee launched a series of brazen attacks and successfully drove McClellan from Virginia.

Johnston later commanded Confederate forces in the Western Theater, where he again clashed with Davis over his cautious tactics during the Vicksburg Campaign. Tasked with halting Gen. William T. Sherman’s march from toward Atlanta in 1864, Johnston continued his policy of strategic retreat, which he believed would preserve his army and allow him to maneuver defensively. Sherman eluded Johnston’s army and inched closer toward Atlanta throughout the spring of 1864. By July, Davis was out of patience. He replaced Johnston with Gen. John Bell Hood just before the Battle of Atlanta.

Davis eventually reinstated Johnston as commander of a loosely collected department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida, but the Confederacy was nearing its end. Johnston surrendered the Army of Tennessee to Sherman in April of 1865. Johnston and Davis remained at odds after the war, but the general maintained friendships with some of his former rivals and even served as a pallbearer at William T. Sherman’s funeral in February 1891.

Atlanta: Featured Resources

All battles of the Atlanta Campaign

Related Battles

34,863

40,438

3,722

5,500