Fort Fisher

Second Battle of Fort Fisher

New Hanover County, NC | Jan 13 - 15, 1865

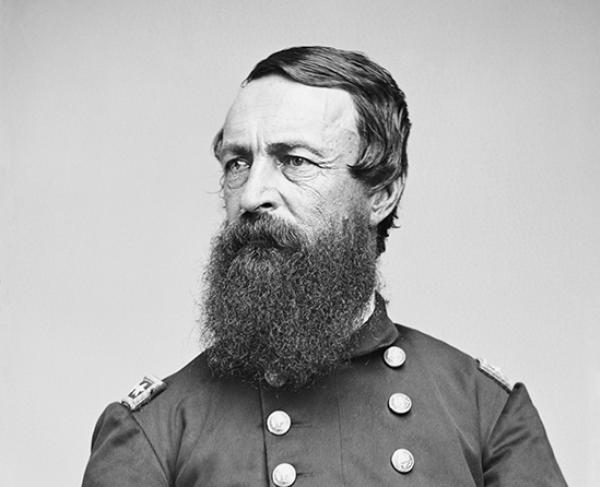

In January of 1865, a joint Army and Navy forces, under the command of both Union Rear Admiral David D. Porter and Major General Alfred Terry, attacked and captured Fort Fisher, which defended the last open port in North Carolina and the Confederacy.

How It Ended

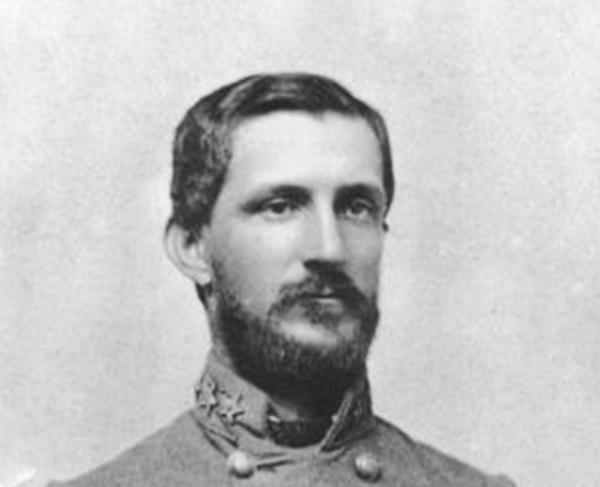

Union Victory. After several hours of intense fighting and having his defenses overrun, a wounded Maj. Gen. William H.C. Witting decided to surrender his garrison of 1,900 men to the Union army.

In Context

By the winter of 1865, Fort Fisher guarded the last remaining open port for the Confederacy at Wilmington, North Carolina. Despite failing to take it in December of 1864, Gen. Ulysses S. Grant decided overtake the fort a second time and sent a Union force of nearly 9,000 men under the command of Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry and several ships under the command of Rear Admiral David D. Porter to take the fort and its 1,900 defenders.

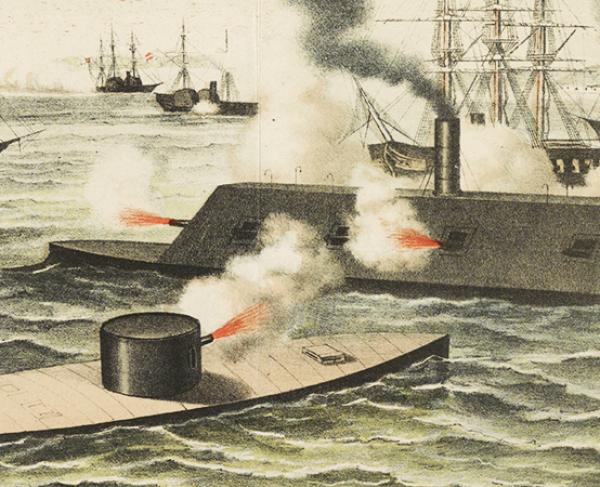

After the Union army and navy sealed off Mobile Bay in August of 1864, only one major port remained open for the Confederacy: Wilmington, North Carolina. This port could be accessed via the Cape Fear River, which ran north-south on the city’s west side before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean some 20 miles south of the city. A peninsula of land on the east side of the river sheltered the town and ships from the Federal blockading squadron in the Atlantic Ocean. Bolstering the area’s natural defense was a series of Confederate fortifications, with the primary fortification being Fort Fisher. This upside-down L-shaped fort was dubbed the “Gibraltar of the Confederacy.”

The first Battle of Fort Fisher, fought from December 23 to 27, 1864, and was more of a Gallipoli than a Normandy: an ill-timed naval bombardment tipped off the Confederate defenders, and a Federal ship packed with tons of explosives failed to make contact with Fort Fisher’s defenses and harmlessly blew up at sea. When the Federal infantry did land, they quickly evacuated. After the debacle, Union commander Benjamin F. Butler was relieved of command.

In January of 1865, a second attempt was made to secure Fort Fisher, and this time the Federals placed Maj. Gen. Alfred Terry and Rear Adm. David D. Porter in command. Terry collected nearly 10,000 Union army soldiers while Porter arrayed 58 ships offshore. Both commanders formed a battle plan where Porter would pummel the Confederate defenses and Terry would land the army on shore. Once ashore, a division of United States Colored Troops (USCT) would advance north up the peninsula and assume a blocking position—their primary mission was to hold back any Confederate reinforcements. The second force of Union infantry would establish a line facing south and attack the landward wall of Fort Fisher. Finally, a force of sailors and the United States marines, some 2,000 in all, would land and attack the seaward wall of the fort.

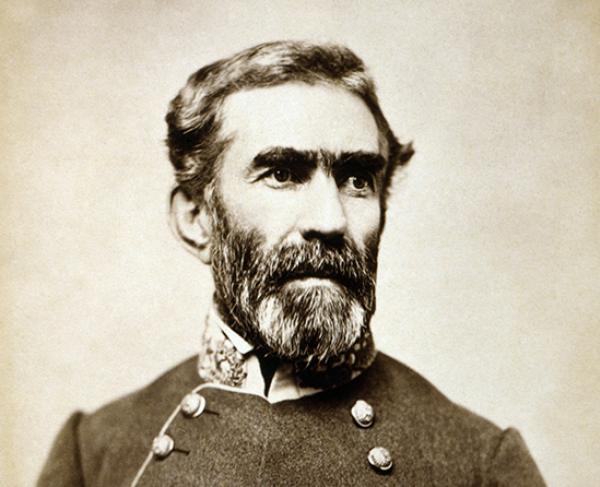

On the night of January 12, 1865, General Alfred Terry’s joint Navy and Army forces made it to the shores of Fort Fisher. For the next two days, Federal ships opened fire on the garrison, firing so frequently it was impossible for the Confederate soldiers stationed inside to repair the damages to the fort. On January 15, the Union army attacked the fort with nearly 2,000 Marines and sailors. Although greatly outnumbered, the Southern soldiers clung tenaciously to their defenses. Meanwhile, Confederate Maj. Gen. William H. C. Whiting pleaded with Braxton Bragg for reinforcements. Bragg refused, not taking the situation at all seriously. Finally, after repeated pleas from Whiting, Bragg sent Alfred Colquitt to the fort with orders to relieve Whiting.

1,057

1,900

By the time Gen. Alfred Colquitt arrived, Confederates were evacuating the fort, and Whiting and Lamb lay wounded. After hours of battle, the Confederates surrendered the fort. The Southern defenses around Wilmington crumbled, and the city fell to Union soldiers roughly one month later. The last Confederate port was locked shut, and the flow of outside supplies ceased to reach the languishing Confederate field armies.

Since the start of the Civil War, the Union Navy initiated a blockade known as the Anaconda Plan that was poised to cut off vital Confederate seaports from the world market. By the winter of 1864, most Southern ports were captured or cut off, except for Wilmington, North Carolina, the last open Southern port. To capture and cut it off from the Atlantic Ocean, the Union Navy and Army had to take Fort Fisher. By early 1865, the Union officials gathered enough men and ships to take the Fort.

During the three days of the Battle of Fort Fisher, Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg refused to believe the Fort could be taken. Because of these, Bragg denied the majority of garrison commander William H. C. Whiting's pleas to aid the garrison. However, by the third day of the battle, Bragg relented and sent only minor reinforcements, but by the time they reached the Fort, it was already too late as the garrison had already surrendered. After the Forts surrendered, Bragg realized the severity of the situation and even wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis about how much he was mortified.

Fort Fisher: Featured Resources

Related Battles

10,000

8,300

1,057

1,900