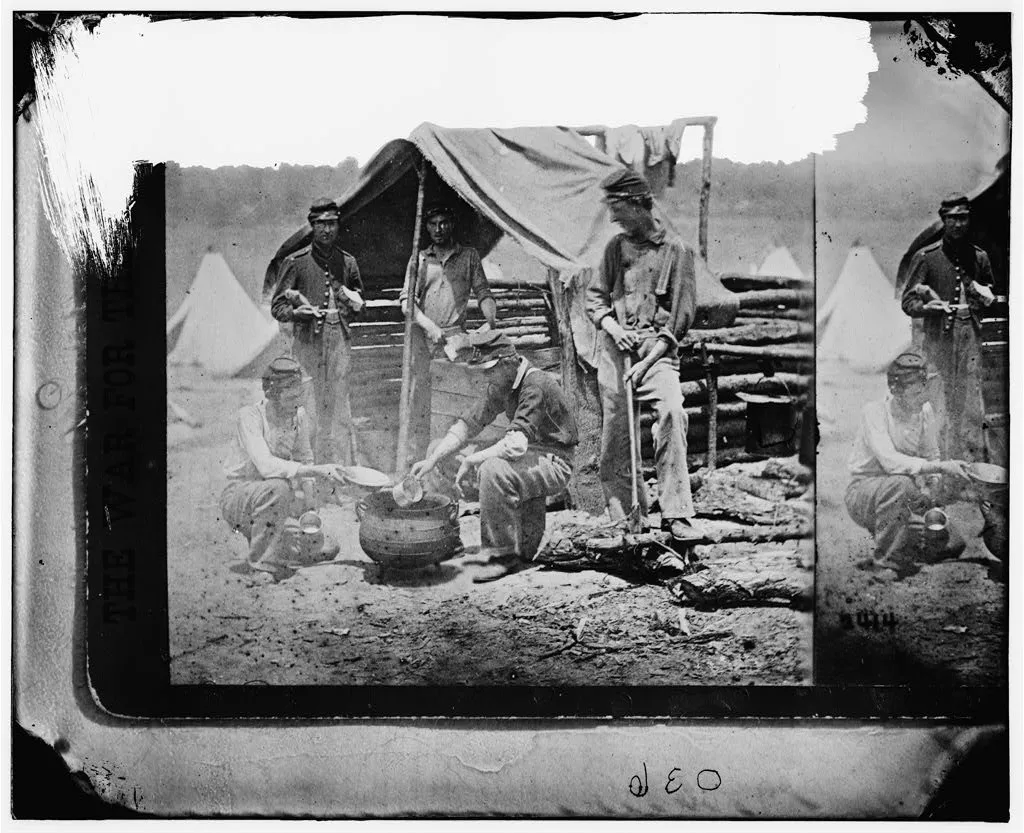

Between camping, marching and battle, Civil War soldiers had plenty of contact with the natural world. Military service often meant trekking to unfamiliar parts of the country and almost always meant long periods of time outdoors.

Many soldiers captured their experiences in diaries and letters. These make up the bulk of the first-person accounts biologist Kelby Ouchley mined for Flora and Fauna of the Civil War: An Environmental Reference Guide. Ouchley’s collection inspired these 5 head-tilting ways the natural world touched soldiers lives’ during the Civil War.

It tempted them.

At best, Civil War rations were modest and monotonous; at worst, they were scarce. It’s no surprise then that soldiers would go to great lengths to supplement their diets, sometimes with harrowing and/or comical results.

Sergeant Rice Bull, 123rd New York Volunteer Infantry, in the trenches of north Georgia on June 21, 1864:

“Dan began to notice his surroundings and looking out in our front discovered something. Turning to me he said, ‘R.C. look at those berries.’ I looked, and about six feet from us but out of reach were a lot of low-growing blackberries, the bushes full of berries. The temptation was too great for Dan to resist. . . . I was as hungry as Dan, so I crawled out beside him and we picked berries as fast as we could, eating as we picked. As we glanced ahead we could see more and more bushes, and as we cleaned up we crawled further and further. Being greatly interested in our work we must have become careless for suddenly a bullet whizzed between our heads that were not more than six inches apart. It tore a hole through Dan’s blouse but did not wound him. We slid back into our hole.”

Lieutenant Charles B. Haydon, 2nd Michigan Infantry, near Washington, on Sept. 23, 1861:

“There was a persimmon tree loaded with rich fruit about 4 rods in front of the line. Its fruit had often been coveted by our men. I concluded to go & get some. I was busily knocking them off with a pole when a rascal fired at me, the ball striking abt 20 feet short & a little to one side. I grabbed up my hands full of persimmons & made no unnecessary delay in returning inside the lines to my proper place.”

Lieutenant John P. Sheffey, 8th Virginia Cavalry, in a letter to his future wife from Fayette County, Virginia, on Nov. 3, 1861:

“Then a determined squad went forth, true votaries of Mercury, the god of thieves, and pressed two Union bee gums. The gums came in laden with stores of honey & the honey comb rich as ever grew in Hybla or on Hymetus. . . . A few poor luckless wights [sic] were stung. What mattered it? One border Ranger, a rara avis on all occasions, eat bees and all. One stung him on the lip & to have revenge he bit the bee & was stung in the mouth & then, enraged, he ‘bolted’ him head, honey, sting and all.”

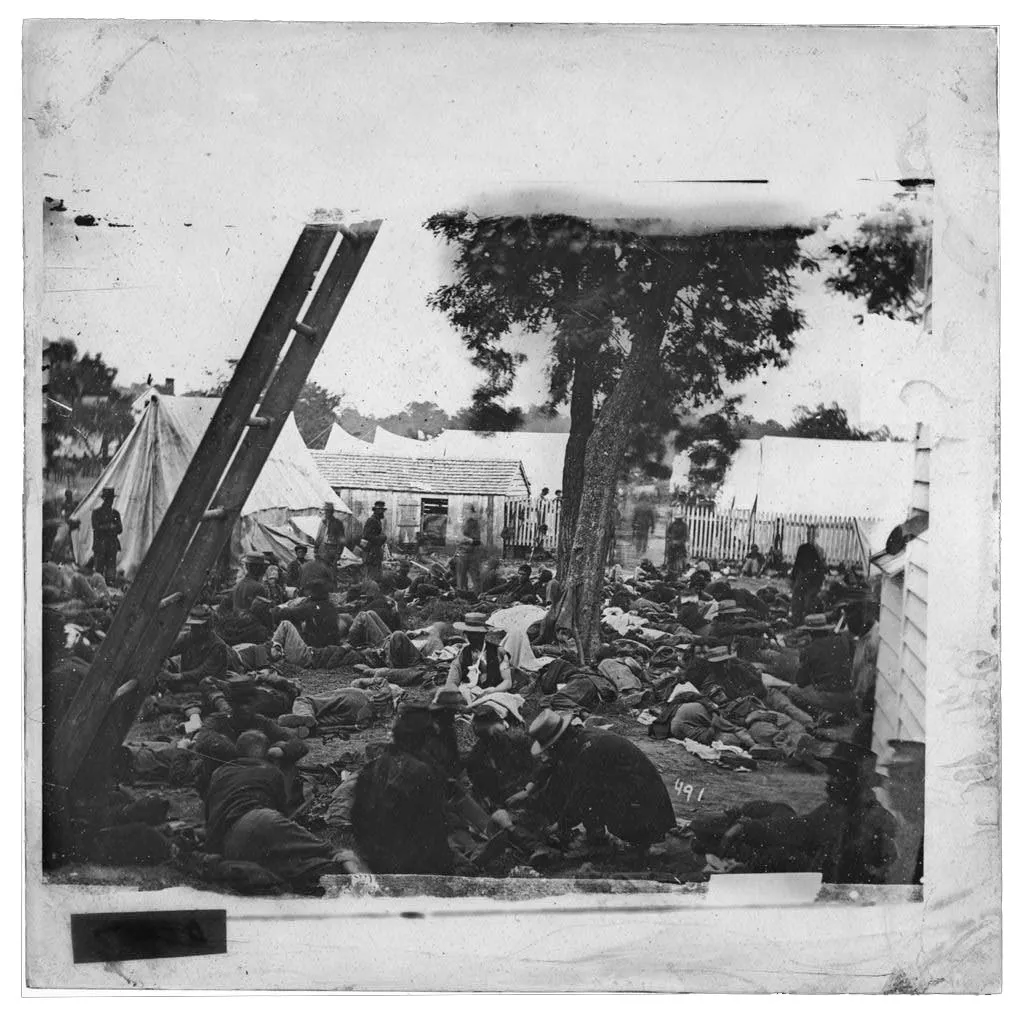

It attacked them.

Nature had much to offer Civil War soldiers, but it wasn’t always benevolent. From alligator attacks to infections, both armies fought on many fronts, against enemies big and small.

Captain Charles B. Haydon, 2nd Michigan Infantry, near Vicksburg, Mississippi, on June 27, 1863:

“The country is not so bad after all as I was at first led to believe. There are not so many snakes or other infernal machines as was represented. The alligators eat some soldiers [!] but if the soldiers would keep out of the river they would not be eaten.”

Lieutenant John G. Earnest, 79th Tennessee Infantry, near Vicksburg, Mississippi, on May 5, 1863:

“A huge old mosquito with claws like a ground hog and a bill half as long as a sergeant’s sword was seated on my shoulder trying to run his bill through my neck and pin me to the ground—fortunately it had lodged against my backbone and before he could make another trial the sentinel came to my relief at a ‘charge bayonets’—when ‘old skeeter’ flew off saying he ‘would be happy to repeat the call.’ I sincerely hoped he would not. I now set about tucking the cover under me all around and finally went to sleep again. About daylight I was awakened by a tremendous roar—when I found the mosquitoes had pulled me to the edge of the bayou, and an old alligator jubilant at the prospect of getting me for his breakfast had given a tremendous laugh which awoke me, and I preferring not to be his breakfast shifted from there. I vowed never to allow myself to sleep on that bayou’s bank again.”

Corporal Rufus Kinsley, a lieutenant in the Second Corps d’Afrique, writing to his father from Ship Island, Mississippi, on May 29, 1864:

“I was very near furnishing a shark with breakfast one morning last week. We were but a short distance from the end of the wharf, in eighteen feet of water, when I, being farther out than the others, excited the appetite of the ravenous man-eater, who at once evinced his anxiety for intimate acquaintance. I made for the wharf, and was so fortunate as to reach it in time to give a fisherman on the wharf opportunity to throw his gig. He failed to strike the creature, but frightened him away.”

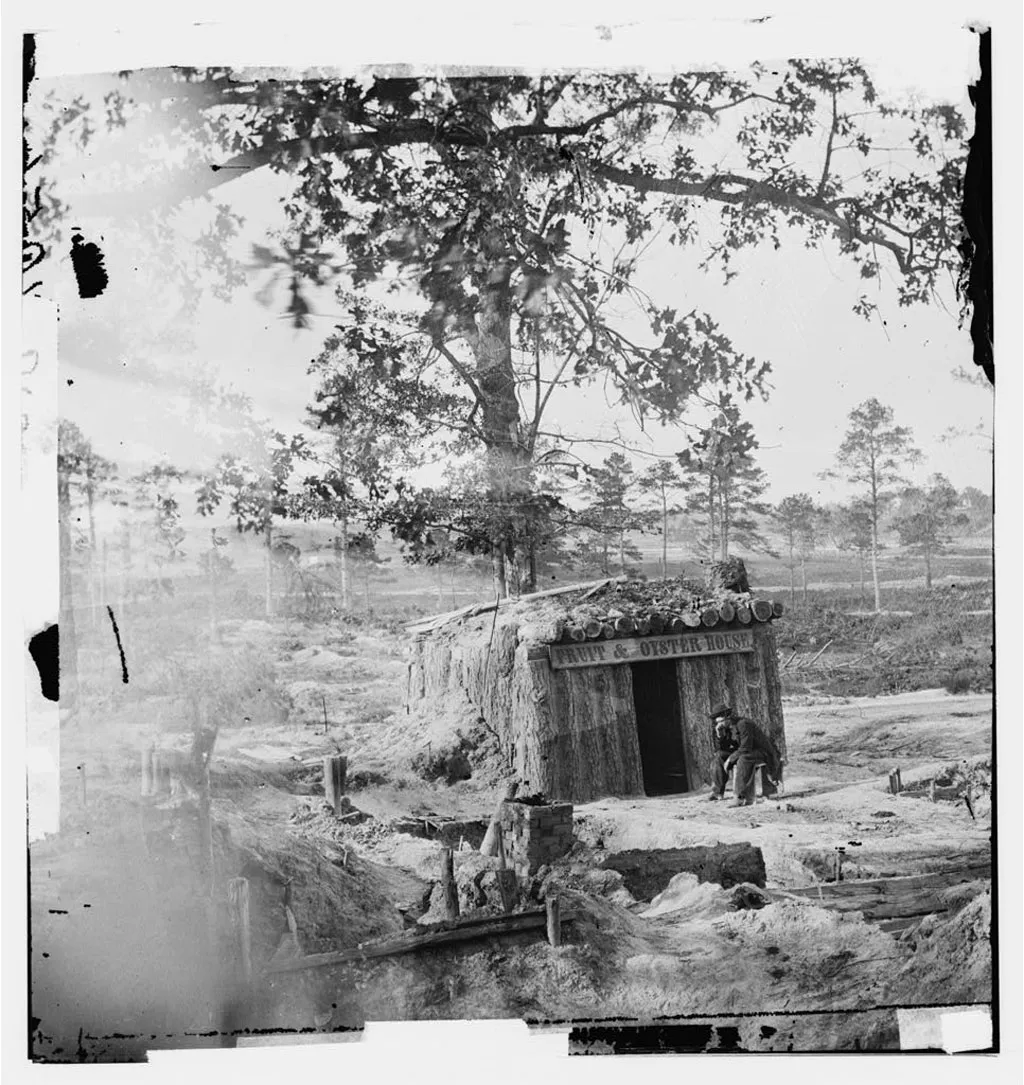

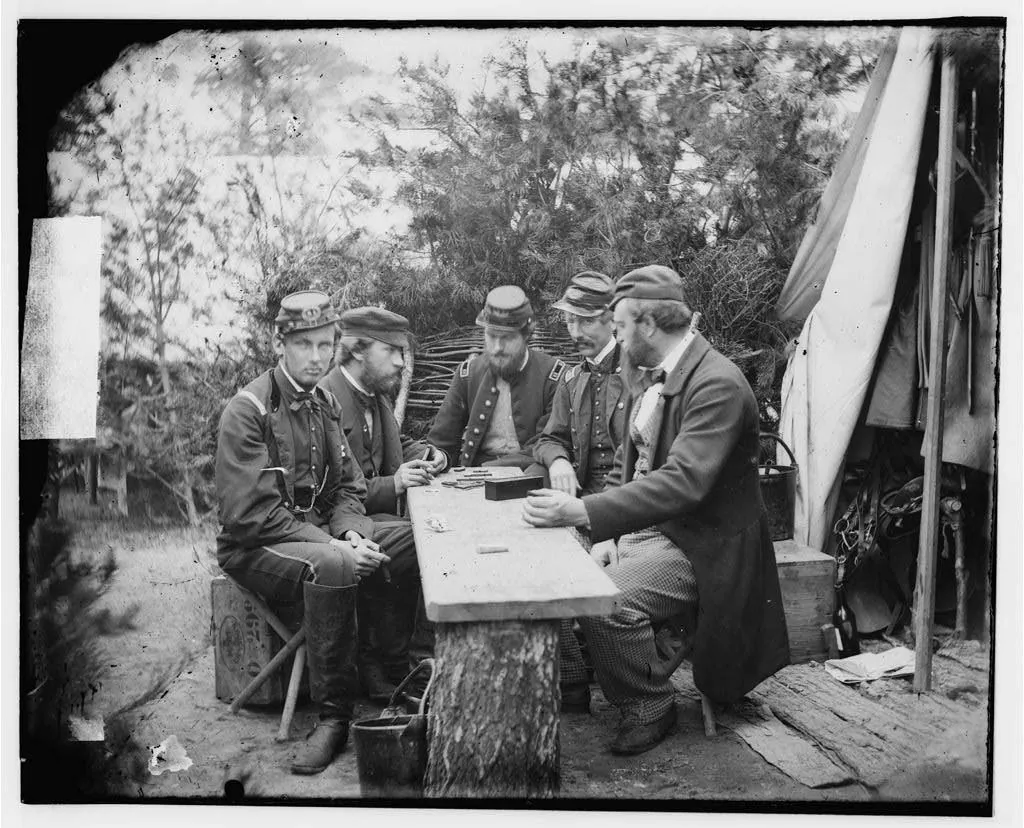

It entertained them.

From tree-planting to louse racing, Civil War soldiers looked to the natural world for both mundane and creative ways to entertain themselves during long stretches of downtime far from home.

Private Theodore F. Upson, 100th Indiana Infantry Volunteers, near Vicksburg, Mississippi, on July 27, 1863:

“I heard a racket yesterday and went to see what it was all about. I found that some of the boys had captured one of the big yellow rattle snakes that are found here and had built a pen of sticks at the foot of a white oak tree that had a limb sticking out over the pen and snake. When they had got it all fixed a man from the 8th Wisconsin came bringing the eagle they carry instead of a Regimental flag. . . . When he came the boys were betting on the result of the encounter betwen the eagle and the snake. . . . The man with the eagle (he is named Old Abe) was taking all bets that were offered saying the eagle will kill the snake. . . . Finaly the carrier gave Old Abe a little toss and he flew up on the limb where he sat turning his head first to one side and then the other, looking down at the angry rattler below. Then his keeper said, ‘Take him Abe.’ And before I could see how it was done he gave a scream, droped from the limb, and with one claw seized the rattler by [t]he head, and with the other on his body literaly tore his head off, then hopped up on the limb again. I would have lost my money sure. The rattler had no chance to bite.”

Private John King, 40th Georgia Infantry, at Camp Chase Prison in Columbus, Ohio:

“One can scarcely imagine that there could be any fun, any real amusement in watching the antics of a miserable louse . . . . but is it possible that a poor forlorn prisoner in the destitution of the meanest poverty, could get a moment’s real fun in playing with the miserable tormentor that had crawled over his back and rendered his life a constant affliction? What think you, gentle reader, of a louse race, of a regular pugilistic encounter between two champions of the genus pediculidae? I have witnessed both and have seen many a potato won and lost by the owners of these tormentors.”

It sustained them.

During the upheaval of the Civil War, plants and animals were indispensible for shelter, food, and even stashing large sums of cash now and then.

Charles T. Quintard, chaplain, 1st Tennessee Infantry, at Columbus, Georgia, on April 22, 1865:

“The fight for the defense of Columbus was quite a brisk affair. . . . At this time I had made no preparation for the coming of the enemy. I had at my house the money [$33,000] collected at the offertory in the morning. This Mr. Noble put in the top of a tall pine tree in the stable yard.”

Lieutenant Edmund D. Patterson, 9th Alabama Infantry, as a prisoner of war on Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie, Ohio, on Sept. 17, 1864:

“For several days some of the boys have been killing and eating rats, of which there are thousands in the prison. I have often been hungry all day long, indeed so hungry that I felt sick, and still I could not screw my courage up to the point of eating rats. But today after getting a few mouthfuls of beef and bread, and having been hard at work most of the day on kitchen detail I was constrained to try a mess of rats. My friend, Jones, had been very lucky and had captured a sufficient number of rats to make a big stew and invited me to try them, and it would have done a hungry man’s soul good just to have seen me eat them. I cannot say that I am particularly fond of them, but rather than go hungry I will eat them when I can get them, though they have become the fashion to such an extent that from twenty five to a hundred are killed every night at each Block and they are already getting scarce. They taste very much like a young squirrel and would be good enough if called by any other name.”

It moved them.

Then as today, the natural world inspired soldiers to wonder and contemplation.

General Robert E. Lee, CSA, in a letter to his wife from Pocahontas County, present-day West Virginia, on Aug. 4, 1861:

“I enjoyed the mountains, as I rode along. The views are magnificent - the valleys so beautiful, the scenery so peaceful. What a glorious world Almighty God has given us. How thankless and ungrateful we are, and how we labour to mar his gifts.”

Private William R. Stilwell, 53rd Georgia Volunteers, in a letter to his wife from near Fredericksburg, Virginia, on March 15, 1863:

“Our present camp is situated in another pine grove. . . . The pine grove extends about a mile east of our quarters and furnishes a beautiful place for one to stroll off by themselves to secret devotion and times while the sun was setting in the far west and the March winds come stealing through the pines making a solemn sound and all nature seems to be hushed in gems of pleasure[.] Here many times have I bowed to offer up my evening prayer for dear friends at home and to commit them to God’s care and mercy.”

Union Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams describing the night before the beginning of the battle of Chancellorsville in a letter to his daughter from Stafford Court House, Virginia, on May 18, 1863:

“The whippoorwills, which are thicker here than katydids up north, were whistling out their ‘whip-poor-wills’ as if there was nothing but peace on earth, and save the occasional crack of the rifle away off on the left there was a solemn stillness which was almost oppressive. Two immense hostile armies, over two hundred thousand armed men, lay within almost the sound of one’s voice.”

For even more wartime reflections on the natural world, we recommend reading Flora and Fauna of the Civil War: An Environmental Reference Guide for yourself. For more history and analysis about the Civil War, we’ve got you covered.