Bunker Hill | June 17, 1775

The day after George Washington’s appointment to command the Continental Army, the American and British forces engaged in one of the bloodiest battles of the Revolutionary War. Washington was still in Philadelphia preparing for his journey to Boston, when the armies of General Artemas Ward and General Thomas Gage engaged in the Battle of Bunker Hill.

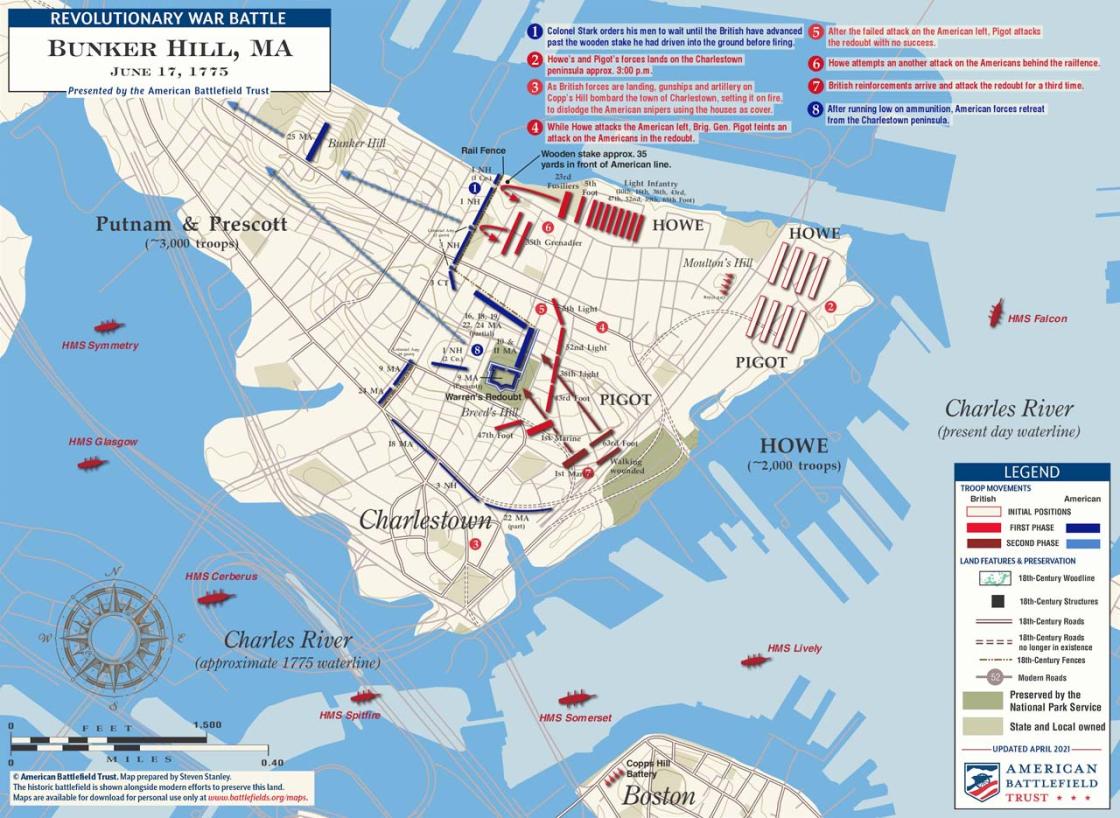

The American force outside of Boston grew in size and strength in the weeks following the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Militiamen from Connecticut, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and what would later become the state of Vermont streamed into the vicinity of Boston. While the quality of the American soldiers was questionable at best, their sheer numbers troubled Gage. Flush with reinforcements and new subordinates, Gage met with three officers who played key roles in the war in North America and all whom failed time and again to quell the rebellion. Gage held a council of war with Gens. William Howe, Henry Clinton, and John Burgoyne. The problem that lay before them was that the Americans assumed a position on a peninsula of land (the Charlestown Peninsula) bordered by the Mystic and Charles Rivers, and that was only accessible to the British via an amphibious landing. After debate among the Americans, it was decided that they would fortify two of the three high points on the west side of the peninsula—Bunker and Breed’s Hills. As Breed’s Hill sat closer to the British (and at an elevation about 40 feet lower in height) the Americans chose to fortify Breed’s Hill first followed by Bunker Hill. Gage and his subordinates debated the situation, with Clinton advocating for a landing in the rear of the Rebels where they could smash them from their rear and isolate them on the peninsula. Howe advocated for a direct assault. The King’s soldiers would attack the unsecure Rebel left and outflank the enemy from their position. Howe’s proposal won the day.

The Rebels did not play to the British tune. General John Stark from New Hampshire recognized that the left flank was exposed along the south bank of the Mystic River. He and his men assembled a makeshift split-rail barricade to blunt any flanking action employed by the British.

On the sultry afternoon of June 17, 1775, Gage and his commanders ordered British regulars and grenadiers to be transported across Boston Harbor and disembarked in lower Charlestown. Howe led King George’s troops in the assault, but the situation had changed since the officer advocated his plan. The American left was not open and flanking column of eleven companies of light infantry were stopped cold as the made their way along the narrow beach. A second attempt was made to dislodge the fence defenders in concert with a frontal assault on the main redoubt atop the hill. This attack, too, failed. A third attack against the American fortifications atop Breed’s Hill finally carried the day for the British. Once again marching head on into musket fire, British tenacity and a lack of ammunition on American side finally carried the day for Gage and Howe. Henry Clinton declared it was “A dear bought victory, another such would have ruined us.” British losses amounted to roughly one-third of the men engaged. Within weeks Washington arrived to assume command of his army, and undertake siege operations. For now, Patriot forces held the advantage in New England.

Related Battles

450

1,054