Argument of Roger S. Baldwin Before the Supreme Court in the Case of U.S. Appellants vs. Cinque, and Other, Africans of the Amistad: 1841

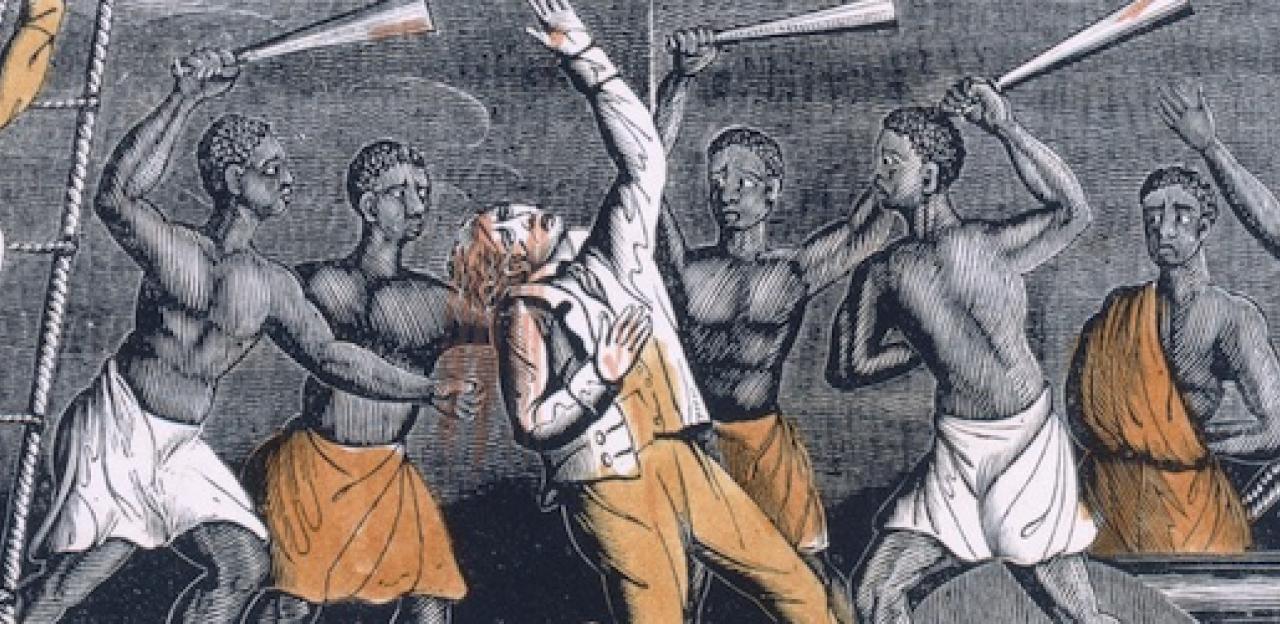

In 1839, the Spanish schooner La Amistad sailed from Sierra Leone to the Caribbean with human cargo destined for enslavement in the Americas. En route, the illegal captives rebelled against their captors, killed the ship captain, and directed the rest of the crew to sail them back to their home. Instead, the Spanish navigators sailed the ship to the United States and were apprehended. The Amistad Affair became a country-wide sensation, and New England abolitionists fought for the detained Africans’ freedom and eventual return to Africa. The case reached the Supreme Court in 1841, which held the lower court conviction that the capture and transfer of human cargo on La Amistad was illegal, that any force used to escape their kidnapping was justified, and that those captured on the ship could not be enslaved.

ARGUMENT

OF

ROGER S. BALDWIN,

OF NEW HAVEN,

BEFORE THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

IN THE CASE OF THE

UNITED STATES, APPELLANTS,

vs.

CINQUE, AND OTHERS, AFRICANS OF THE AMISTAD.

NEW YORK:

S. W. BENEDICT, 128 FULTON STREET.

1841.

ARGUMENT OF R. S. BALDWIN, BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

May it please your Honors,--

In preparing to address this honorable Court on the questions arising upon this record, in behalf of the humble Africans whom I represent,--contending, as they are, for freedom and for life, with two powerful governments arrayed against them,--it has been to me a source of high gratification, in this unequal contest, that those questions will be heard and decided by a tribunal, not only elevated far above the influence of Executive power and popular prejudice, but from its very constitution exempt from liability to those imputations to which a Court, less happily constituted, or composed only of members from one section of the Union, might, however unjustly, be exposed.

In a case like this, involving the destiny of thirty-six human beings, cast by Providence on our shores, under circumstances peculiarly fitted to excite the sympathies of all to whom their history has become accurately known, it is much to be regretted that attempts should have been made in the official paper of the Government, on the eve of the trial before this Court of dernier resort, to disturb the course of justice, not only by passionate appeals to local prejudices, and supposed sectional interests, but by fierce and groundless denunciation of the honorable Judge before whom the cause was originally tried, in the Court below: and, as if this were not enough, that two miserable articles from a Spanish newspaper, denouncing these helpless victims of piracy and fraud, as murderers, and monsters in human form, should have been transmitted by the minister of Spain to the Department of State, and published in an Executive communication to the Senate, on the very day on which the hearing commenced in this honorable Court.

I do not allude to these improprieties from any apprehension of their influence here, but because I feel it to be a duty thus publicly to reprobate a course of proceeding, the obvious tendency of which is to excite jealousy and distrust, and thereby to impair the just confidence with which an unprejudiced community have ever regarded the judgments of this high tribunal.

This case is not only one of deep interest in itself, as affecting the destiny of the unfortunate Africans whom I represent, but it involves considerations deeply affecting our national character in the eyes of the whole civilized world, as well as questions of power on the part of the government of the United States, which are regarded with anxiety and alarm by a large portion of our citizens. It presents, for the first time, the question whether that government, which was established for the promotion of JUSTICE, which was founded on the great principles of the Revolution, as proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence, can, consistently with the genius of our institutions, become a party to proceedings for the enslavement of human beings cast upon our shores, and found in the condition of freemen within the territorial limits of a Free and sovereign State?

In the remarks I shall have occasion to make, it will be my design to appeal to no sectional prejudices, and to assume no positions in which I shall not hope to be sustained by intelligent minds from the South as well as from the North. Although I am in favor of the broadest liberty of inquiry and discussion,--happily secured by our Constitution to every citizen, subject only to his individual responsibility to the laws for its abuse,--I have ever been of the opinion that the exercise of that liberty by citizens of one State in regard to the institutions of another should always be guided by discretion, and tempered with kindness.

The facts on which the counsel for the appellees move to dismiss this appeal as they appear on the record, or are averred in their motion and not denied, are these:--

The schooner Amistad, on the 26th of August, 1839, arrived in Long Island Sound, in the possession of the appellees, and was anchored about half a mile from the northerly shore of Long Island, near Culloden Point.

She had sailed from Havana on the 28th of June, bound to Guanaja under the command of her then owner, Raymon Ferrer, having on board, as passengers, two Spaniards, Josè Ruiz and Pedro Montez, and fifty-four "native Africans," admitted to have been "recently imported from Africa," of whom the appellees are a part. They were put on board the schooner on the night previous to her sailing, by Ruiz and Montez respectively, as their slaves; under color, (with the exception of the boy Kali,) of two custom-house permits, authorizing certain Ladinos, described only by Spanish names, and said to belong to them respectively, to go by sea to Puerto Principe. When the schooner arrived in Long Island Sound, none of her original crew, except Antonio, the slave of Captain Ferrer, were on board. She had no flag flying to denote her national character or former ownership. The captain and cook had been killed soon after she sailed from Havana, by some of the Africans in their efforts to recover their liberty; and the rest of the crew had abandoned the schooner in the boat. From that time, the schooner and the two Spanish passengers, and the boy Antonio, were under the control of the Africans, who were themselves, de facto, free.

Most of them had been on shore, within the territorial limits of the State of New York, whose laws prohibit slavery, and a part of them were then on shore in communication with the inhabitants, on whose protection they had thrown themselves, when the schooner was boarded by an officer and boat's crew of the United States brig Washington, and the Africans on board, as well as those on shore, were, at the instance of the two Spaniards, who claimed them as their slaves, seized by the order of Lieutenant Gedney, a naval officer in the service of the United States; forcibly withdrawn from the territorial jurisdiction of the State in which they were found, and brought, with the schooner of which they were in possession, into the District of Connecticut. The Africans were ignorant of any language but that of their nativity, and were known by Ruiz and Montez to have been recently imported from Africa.

In May, 1818, the Spanish government, by its minister, Don Onis, communicated to the government of the United States the treaty between Great Britain and Spain, bearing date the 23d of September, 1817, for the abolition of the slave-trade, and the ordinance of the King of Spain, issued in pursuance thereof, of the date of December, 1817, prohibiting the traffic, and directing that its victims shall be declared free, in the first port in his dominions at which they shall arrive. In February, 1819, the treaty between Spain and the United States was revised at Washington, after a protracted negotiation between Mr. Adams, then Secretary of State, and the Spanish minister, Don Onis.

On the arrival of the schooner at New London, on the 29th of August, 1839, before the intervention of the Spanish minister at Washington, the Africans were placed in the custody of the law, under process of the District Court of the United States, as a Court of Admiralty, against them as property, on the libel of Lieutenant Gedney and his officers for salvage.

On the 6th of September, 1839, the Spanish minister wrote to the Secretary of State, demanding that the schooner and her cargo, be delivered to the owner without salvage; and that "the negroes" (whom he represented to belong to Ruiz and Montez,) "be conveyed to Havana, or be placed at the disposal of the proper authorities in that part of her Majesty's dominions, in order to their being tried by the Spanish laws which they have violated; and that in the mean time they be kept in safe custody in order to prevent their evasion."

Subsequently to this requisition by the Spanish minister, viz., on the 18th of September, 1839, Josè Ruiz and Pedro Montez, respectively, filed their libels in the District Court, and prayed process of attachment against the Africans as their property, averring that they were within the jurisdiction of the court, and insisting that they "ought, by the laws and usages of nations and of the United States, and according to the treaties between Spain and the United States, to be restored to them, without diminution and entire." The process of the court was issued according to their request, and the appellees were again taken into custody thereon as property. Claims were, at the same time, filed by Ruiz and Montez, respectively, in answer to the libel of Lieutenant Gedney for salvage.

After the parties in interest were thus before the court, the District Attorney of the United States on the 19th of September, filed a suggestion that the Spanish minister had presented to the government of the United States a claim, that the appellees are the property of Spanish subjects, and that they arrived within the jurisdictional limits, and were taken possession of by a public armed vessel, of the United States, under such circumstances as to make it the duty of the Government to cause them "to be restored to the true proprietors and owners thereof, as required by the treaty subsisting between the United States and Spain."

And therefore the District Attorney, in behalf of the United States, prays the Court, on its being made legally to appear that the claim of the Spanish minister is well founded and conformable to the Treaty, to make such order as may best enable the United States to comply with their Treaty stipulation; but if it should appear that the negroes were transported from Africa, and brought within the United States,contrary to the laws of the United States, that the Court will make such order as will enable the President to send them to Africa pursuant to the act of Congress in such case provided.

On the 19th of November, the District Attorney filed another suggestion similar to the first, omitting only the alternative prayer; and on each of these suggestions, a warrant of seizure was issued by the Court, and the Africans were again taken into custody thereon.

To these several libels, claims, and suggestions, the Africans, who, when seized, were in the condition of freemen, capable of having and enforcing rights of their own, severally answered: that they were born free,--and were kidnapped in their native country, and forcibly and unlawfully transported to Cuba;--that they were wrongfully and fraudulently put on board of the Schooner Amistad by Ruiz and Montez, under color of permits, fraudulently obtained and used; that after achieving their own deliverance they sought an asylum in the State of New York, by the laws of which they were free; and that while there, they were illegally seized by Lieutenant Gedney, and brought into the District of Connecticut.

The District Court found these allegations in substance to be true, and therefore dismissed Lieutenant Gedney's libel for salvage on the Africans; and also dismissed the libels of Ruiz and Montez, and the suggestion or claim made by the United States on their behalf; but in accordance with the alternative prayer by the District Attorney in behalf of the United States, decreed that the Africans should be delivered to the Executive to be sent back to Africa.

From the finding and decree of the District Court, neither Ruiz nor Montez, nor Gedney have appealed. They voluntarily sought, by their libels, the action of the Court, and submitted to the decision against them. They might have appealed, but chose not to avail themselves of the privilege.

The Spanish minister never made himself a party to the proceedings in the Court, either as the Representative of the Government, or of the subjects of Spain. It is true, the decree of the District Court speaks of "the claim of the minister of Spain which demands the surrender of Cinque and others,"--as if it were a claim made by him in Court, and dismisses it. It also speaks of the claims of Ruiz and Montez as being "included under the claim of the minister of Spain," and dismisses them also.

But the Record shows that no appearance or claim was ever made in Court, by the Spanish minister; and it appéars by the correspondence transmitted to the House of Representatives, (Doc. 185, 26 Cong. p. 6, 7, 8,) that his demand on the Executive for the surrender of the Africans as criminals, was made on the 6th of September, 1839, several days anterior to the filing of the libels of Ruiz and Montez in the District Court against them as property. Of course their libels and claims could not have been included in any claim of the Spanish minister, on which the Court was called to decide. Indeed the Spanish minister would have had no right to appear in the Court of Admiralty as the representative of Spanish claimants of property, who were personally in Court pursuing their claims for themselves. See 1 Mason, 14; 10 Wheat. 66. And so far was he from actually appearing, or desiring to appear as a suitor in the Court, that he has continued to the present time to protest against the exercise of jurisdiction by any of the tribunals of the United States over the subject matter in controversy. Cong. Doc. 185, p. 21. H. R. 1840, and Sen. Doc. 179, 1841, p. 6. He has neither taken, himself, an appeal from the decree of the Court, nor has he authorized an appeal to be taken by the United States in his behalf. The Government of the United States, therefore, are acting in these proceeding as volunteers, having no interest of their own, and no authority to represent or affect the fights of others. And yet, singular as it may seem, the only appeal which has been taken from the decree of the Court below is the appeal of the United States in the following words: "And after the said decree is pronounced the said United States, claiming as aforesaid in pursuance of a demand made upon them by the minister of her Catholic Majesty the Queen of Spain, to the United States, move an appeal, &c."

The Counsel for the Africans move the Court to dismiss this appeal, on the ground that the Executive Government of the United States had no fight to become a party to the proceedings against them as property, in the District Court, or to appeal from its decree.

1st. It was an unauthorized interference of the Executive with the appropriate duties of the Judiciary.

By the constitution of the United States the sovereignty, originally in the people, was confided by them, so far as was deemed necessary for the purposes of a National Government, to three separate departments; each in the exercise, of its legitimate powers, sovereign and independent of the other. And, it was long since remarked by an eminent jurist, that when either branch of the government usurps that part of the sovereignty which the constitution assigns to the other branch, liberty ends, and tyranny begins. The constitution designates the portion of sovereignty to be exercised by the judicial department, and among other attributes devolves upon it the cognizance of "all cases in law or equity arising under the constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made or which shall be made under their authority," and "all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction;" and renders it sovereign, as to determinations upon property, whenever that property is within its reach. See 3 Dall. 12, 13; Bee's Adm. 278.

The Africans of the Amistad who, when found by Lt. Gedney, were de facto free, and in part at least within the territorial limits of a free state, were seized by him, at the instance of Ruiz and Montez, as their property. They were libelled with the vessel and cargo, as property, for salvage, and were taken into the custody of the law, under a warrant of seizure from the District Court. If they were in fact property, and liable to be treated as such, by any department of the Government of the United States, they were then in the custody of a judicial tribunal, competent to award and restore the possession to the true proprietor, whenever his title should be proved. A "ease" had arisen in which the question of freedom or property, which lies at the foundation of all jurisdiction over the Africans, was involved; and in which, if the Court had jurisdiction over them as property, its power was necessarily sovereign and exclusive. See 3 Dall. 13; 7 Wheaton, 284--310; Bee's Adm. Rep. 278, 9.

If, under any circumstances, it would have been competent for the Executive, on a demand by the Spanish minister, to investigate the facts, and decide on conflicting claims to property in the custody of a public officer, claimed by foreign subjects under a treaty, (which may well be doubted, see Wheaton's El. 289; 7 Wheaton's Rep. 284, 310,) it seems very clear that the Spanish claimants were at liberty, if they preferred it, to avail themselves of the stipulation in the treaty, and seek their remedy by an application to the court. For it is expressly provided by the 20th article of the Treaty with Spain: "that the inhabitants of the territories of each party shall have free access to the Courts of Justice of the other, and shall be permitted to prosecute suits for the recovery of their properties, &c., whether the persons whom they may sue be citizens of the country in which they may be found, or any persons who may have taken refuge therein."

And it seems equally clear that after property in controversy has been placed in custody of the law by process in rem, and the claimants have filed their libels, and voluntarily submitted to the jurisdiction of the Court, the rights of the litigating parties must be decided by the judicial and not by the executive power. 2 Mason, 436,463; 7 Wheat. 310, 11, Tazewell arg.; Bee's Rep. n. 277, 8; Const. Art. 3. § 3. See also, Mr. Forsyth's letters to the Spanish Minister, Dec. 12, 1839; Doc. 185, H. R. 1840, p. 27; Senate Doc. 179, 1841, p. 12, 29. See also, Chief Justice Taney's opinion, when Attorney General, Aug. 4, 1831; Doe. 199, H. R. 1840, p. 70.

So far as the Africans were concerned, all the parties in interest were before the Court, when the United States intervened with their claim or suggestion; for it is not pretended that the Africans, if they were property, belonged to any other Spanish subjects than Ruiz and Montez. If it was the duty of the United States, by reason of any provision in the treaty, to deliver the Africans as property to their Spanish claimants, it was a duty which the Court was obliged by the treaty to perform, after the property was placed in its custody, at the suit of the claimants, if they succeeded in establishing their title. There was no necessity for the intervention of the Executive to stimulate the Court to the performance of its duty. And if, under such circumstances, the Spanish minister had invoked the aid of the Executive in the manner suggested by the District Attorney, it would seem only to have been necessary for the Executive to reply, that the parties in interest were pursuing their claims before a judicial tribunal, in whose custody the subject of litigation had been placed, and by whose decision alone it could be controlled.

No sovereign rights of a foreign government were here in question, to oust the Court of its jurisdiction over the property, as in the case of the Exchange, (7 Cranch, 116,) where a public armed ship in the service of a foreign government, having entered the port of Philadelphia, under an implied promise of exemption from the jurisdiction of the country, was libelled as the property of an American citizen, and seized under process of the District Court. A foreign sovereign could not of course appear before our judicial tribunals to vindicate his public rights; and it was therefore very properly holden that a necessity existed for allowing the fact, which deprived the Court of its jurisdiction, to be disclosed by the suggestion of the Attorney for the United States.

But in this case the District Attorney suggests that the Africans are demanded by the Spanish minister merely as private property, to be delivered to their owners. And, instead of denying, as in the case of the Exchange, the jurisdiction of the Court, he expressly admits it in his suggestion of the 19th of November, and applies for the issuing of its process, although the Africans were already in custody on the libels of Gedney, and of Ruiz and Montez.

What occasion, then, was there for any interference in this case by the Executive Government of the United States to control or direct the action of the Court? Are not treaties, and all the duties imposed by them in regard to property in litigation, obligatory on the Court, as the supreme law of the land, as much without the intervention of the Executive as with it? Did the suggestion, that the claims of Ruiz and Montez were urged by the Spanish minister, add anything to their strength or justice? Ought it, in any way, to influence or affect the decision of the Court?

For what purpose, then, I again ask, do the United States appear in these proceedings? They make no allegations, and put no fact in issue in regard to the Africans. They admit the jurisdiction of the Court; and claim no interest of their own to be affected by its decision. The question of freedom or slavery was in issue only between Ruiz and Montez and the Africans. It was decided in favor of the Africans, by a court whose jurisdiction was expressly admitted by the Spanish libellants. Between those parties, therefore, it was conclusively decided not only that the Africans were not the property of Ruiz and Montez (9 Wheaton, 410; 8 Peters, 4--10; 9 Wheaton, 367,) but that they were not property, but freemen, in possession of all their natural rights.

As Ruiz and Montez have not appealed from this decision, and the Spanish minister has never authorized an appearance or an appeal in his behalf, (See Doc. 185, H. R. 1850, and Senate Doc. 179, 1841,) it follows that there is no allegation by any party before this court, that the Africans are the property of any one, or indeed that they are property;--a fact, the establishment of which, as has already been remarked, lies at the very foundation of the jurisdiction of any court or department of the Government in regard to them. And the only allegation that is made, namely, that they have been demanded as property, by the Spanish minister, to be surrendered to their owners, is utterly untrue. For the Chevalier de Argaiz, in his letter to Mr. Forsyth, of Nov. 26, 1839, expressly declares "that the legation of Spain does not demand the delivery of slaves, but of assassins." Yet it is udder process issued on that suggestion merely, that they are now detained in custody, after a judicial decision in favor of their freedom, from which the Spanish libellants have not appealed.

Who, then, can again draw in question a fact thus solemnly decided? By whom is it attempted? What is the issue this Court is called upon to decide? and between what parties is it made?

The United States, in their own right, having no interest in the subject matter in controversy, could have had no motive for making themselves a party to the proceedings, except to claim the delivery of the Africans to the Executive as their protector, to enable him to fulfil the beneficent designs of the Act of Congress of 1819. It was in that capacity that the Executive Government appeared and acted in the case of the Antelope, (10 Wheaton, 66,) to deliver, not to enslave; to restore the oppressed to their country, not to aid the robber in rivetting their chains. The similar claim made by the United States in the present case, was sanctioned by the Court; who decreed that the Africans should be delivered to the Executive to be transported to Africa, pursuant to the act of Congress, in precise conformity with the request of the District Attorney. How then could the United States be aggrieved by the decree so as to entitle them to an appeal?. What allegation of theirs does it contradict?. What fact put in issue by them does it deny?. None whatever. They asked for no decree other than such as was actually made, except on the contingency that the Court should find, on the allegations of the Spanish claimants, that the Africans were their property. That fact was not found by the Court, and the Spanish claimants, between whom and the Africans the question of property or freedom was put in issue, have not appealed from the decision.

The Africans, although as freemen, they might well complain of it, have taken no appeal from the decree which places them in the hands of the Executive. The Government of the United States have not appealed on their own account, to avoid the burthen of transporting the Africans to their homes. In that capacity they could not appeal from the decree they prayed for, nor have they attempted it. The appeal itself exhibits on the face of it the character in which it is taken by the United States: "The United States, claiming as aforesaid in pursuance of a demand made upon them by the Minister of Her Catholic Majesty, move an appeal." And that is the only appeal which has been taken from the decree of the Court below.

What clause in the Constitution or what law confers on the Executive the right of appearing as a suitor in the courts of the United States to prosecute claims to property of any sort as the representative of foreigners, and to appeal from court to court in their behalf?. It will not be pretended that any such power is expressly conferred. If it exists, it must be implied, because it is necessary to the peformance of some duty imposed on the National Executive in regard to such property. But no such duty or necessity can exist where the property in controversy is in custody of the law, or subject to the process and jurisdiction of the courts. In such cases the judicial tribunals are accessible to all who claim an interest in the property. Foreigners as well as citizens can there appear, and claim and prosecute for themselves; and if they are absent from the country, the consul or other official functionary of their government is permitted to appear in their stead, and vindicate their rights.

The fact that the restoration of property in legal custody is claimed under a treaty, and demanded of the Executive by a foreign minister, in behalf of the subjects of his government, imposes no duty on the Executive in regard to it. The property is not under his control; and the judicial power, being sovereign within its sphere of action, must decide on the claims of the litigating parties without reference to the wishes or suggestions of the Executive. 2 Mason, 436, 463. La Jeune Eugenie.

It is unlike the case of a national demand for a national purpose; such, for example, as a demand of the extradition of a fugitive criminal to a foreign government for punishment, as in the case of Nash, under the treaty with Great Britain; (Bee's Admiralty, 286, note,) or a demand for the surrender of a public armed vessel of a foreign government wrongfully subjected to judicial process, as in the cases of the Cassius (3 Dull. 121) and Exchange, (7 Crunch, 116.)

Those are cases which, from their very nature, pertain to the Executive, and not to the judicial cognizance. But there are a great variety of stipulations in all our treaties for the security of private rights, which are necessarily enforced by the judicial tribunals alone, without the interference of the Executive power. Bee's Admiralty, 286, 7, note.

In cases of capture of belligerent vessels made within our jurisdiction in violation of our neutrality, we are bound by treaty to restore the property, if within our power, to the original owner. "Doubts were at first entertained," during the administration of General Washington, "whether it belonged to the Executive Government, or the Judiciary, to perform the duty of inquiring into captures made within the neutral territory, and of making restitution to the injured party; but it has been long since settled that this duty appropriately belongs to the Federal tribunals, acting as Courts of Admiralty and maritime jurisdiction." Wheaton's El. 289; 4 Wheat. 65, note; 7 Wheat. 284.

While those doubts existed, it was never supposed that the Executive could call upon the courts to aid him in the performance of a duty pertaining to that department. President Washington, in his message of Dec. 3, 1793, (1 Waite's State Papers, 39,) says "If the Executive is to be the resort, it is hoped that he will be authorized by law to have facts ascertained by the courts when, for his own information, he shall desire it."

So, on the other hand, whenever the duty of rendering justice to foreigners is imposed upon the Judiciary of the United States, whether by treaty or otherwise, it is to be presumed it will be as faithfully performed by that department without the intervention of the Executive as with it. And the judgment of the courts upon the rights of the parties to the record, must, as between those parties, be conclusive till reversed by some higher tribunal, to which they have liberty of appeal.

In the present case there could be no necessity for the intervention of the Executive, since the claimants of the Africans appeared in person,--prayed the process of the court against them, and submitted themselves to its jurisdiction, as the treaty gave them a right to do.

2d. But if the Government of the United States could appear in any case as the representative of foreigners claiming property in the Court of Admiralty, it has no right to appear in their behalf to aid them in the recovery of fugitive slaves, even when domiciled in the country from which they escaped: much less the recent victims of the African slave trade, who have sought an asylum in one of the free States of the Union, without any wrongful act on our part, or for which, as in the case of the Antelope, we are in way responsible.

The recently imported Africans of the Amistad, if they were ever slaves, which is denied, were in the actual condition of freedom when they came within the jurisdictional limits of the State of New York. They came there without any wrongful act on the part of any officer or citizen of the United States. They were in a State where, not only no law existed to make them slaves, but where, by an express statute, all persons, except fugitives, &c., from a sister State, are declared to be free. They were under the protection of the laws of a State which, in the language of the Supreme Court in the case of Miln vs. the City of New York, 11 Peters, 139, "has the same undeniable and unlimited jurisdiction over all persons and things within its territorial limits, as any foreign nation, when that jurisdiction is not surrendered or restrained by the Constitution of the United States."

The American people have never imposed it as a duty on the Government of the United States to become actors in an attempt to reduce to slavery men found in a state of freedom, by giving extra-territorial force to a foreign slave law. Such a duty would not only be repugnant to the feelings of a large portion of the citizens of the United States, but it would be wholly inconsistent with the fundamental principles of our Government, and the purposes for which it was established, as well as with its policy in prohibiting the slave trade and giving freedom to its victims.

The recovery of slaves for their owners, whether foreign or domestic, is a matter with which the Executive of the United States has no concern. The Constitution confers upon the Government no power to establish or legalize the institution of slavery. It recognizes it as existing in regard to persons held to service by the laws of the States which tolerate it; and contains a compact between the States, obliging them to respect the fights acquired under the slave laws of other States in the cases specified in the Constitution. But it imposes no duty, and confers no power on the Government of the United States to act in regard to it. So far as the compact extends, the courts of the United States, whether sitting in a free State or a slave State, will give effect to it. Beyond that, all persons within the limits of a State are entitled to the protection of its laws.

If these Africans had been taken from the possession of their Spanish claimants, and wrongfully brought into the United States by our citizens, a question would have been presented similar to that which existed in the case of the Antelope. But when men have come here voluntarily, without any wrong on the part of the Government or citizens of the United States, in withdrawing them from the jurisdiction of the Spanish laws, why should this Government be required to become active in their restoration? They appear here as freemen. They are in a State where they are presumed to be free. They stand before our courts on equal ground with their claimants; and when the courts, after an impartial bearing with all parties in interest before them, have pronounced them free, it is neither the duty nor the fight of the Executive of the United States to interfere with the decision.

The question of the surrender of fugitive slaves to a foreign claimant, if the right exists at all, is left to the comity of the States which tolerate slavery. The Government of the United States has nothing to do with it. In the letter of instructions addressed by Mr. Adams, when Secretary of State, to Messrs. Gallatin and Rush, dated Nov. 2, 1818, in relation to a proposed arrangement with Great Britain for a more active cooperation in the suppression of the slave trade, he assigns as a reason for rejecting the proposition for a mixed commission "that the disposal of the negroes found on board the slave-trading vessels which might be condemned by the sentence of the mixed courts cannot be carried into effect by the United States." "The condition of the blacks being in this Union regulated by the municipal laws of the separate States, the Government of the United States can neither guarantee their liberty in the States where they could only be received as slaves, nor control them in the States where they would be recognized as free." Doc. 48, H. Rep. 2 seas. 16th Cong. p. 15.

It may comport with the interest or feelings of a slave State to surrender a fugitive slave to a foreigner, or at least to expel him from their borders. But the people of New England, except so far as they are bound by the compact, would cherish and protect him. To the extent of the compact we acknowledge our obligation, and have passed laws for its fulfillment. Beyond that our citizens would be unwilling to go.

A State has no power to surrender a fugitive criminal to a foreign government for punishment; because that is necessarily a matter of national concern. The fugitive is demanded for a national purpose. But the question of the surrender of fugitive slaves concerns individuals merely. They are demanded as property only, and for private purposes. It is, therefore, a proper subject for the action of the state, and not of the national authorities.

The surrender of neither is demandable of right, unless stipulated by treaty. See as to the surrender of fugitive criminals, 2 Brock. Rep. 493; 2 Sumner, 482; 14 Peters, 540; Doc. 199 H. R. 26 Cong. p. 53, 70; 10 Amer. State Pap. 151, 3, 433; 3 Hall's Law Jour. 135. An overture was once made by the Government of the United States to negotiate a treaty with Great Britain for the mutual surrender of fugitive slaves. But it was instantly repelled by the British Government. It may well be doubted whether such a stipulation is within the treaty-making power under the constitution of the United States. "The power to make treaties," says Chief Justice Taney, 14 Pet. 569, "is given in general terms . . . . and consequently it was designed to include all those subjects which in the ordinary intercourse of nations had usually been made subjects of negotiation and treaty; and which are consistent with the nature of our institutions, and the distribution of powers between the general and state governments." See 14 Peters, 569, Holmes vs. Jennison. But, however this may be, the attempt to introduce it is evidence that, unless provided for by treaty, the obligation to surrender was not deemed to exist.

3dly. If there was no objection to the appeal on account of the want of interest, or of power in the Executive Government of the United States, in any case, to prosecute an appeal as the representative of others, to aid in the recovery of fugitive slaves, we claim that the appeal in the present case ought to be dismissed, on the ground that it is not competent for any Court of Admiralty of the United States, to recognize as property, the recent victims of the African slave trade, who have achieved their own deliverance from slavery, and arrived here in the condition of freemen. Neither the Executive nor the Courts of the United States can, for such a purpose, give extra-territorial force to the municipal laws of a foreign state. It would be equally at war with the fundamental principles and policy of our government, as with the claims of humanity and justice. No state in this Union regards them as property. As the victims of piracy they are entitled to their freedom when imported by our own citizens, and no principle of comity can require us to regard them as property when claimed by foreigners. 9 Wheaton, 370, 362; 2 Mason, 158--161, 446; 1 Burg. Confl. 741; Story's Confl. 92; 2 Barn. and Cress. 463.

We deny that Ruiz and Montez, Spanish subjects, had a right to call on any officer or Court of the United States to use the force of the government, or the process of the law for the purpose of again enslaving those who have thus escaped from foreign slavery, and sought an asylum here. We deny that the seizure of these persons by Lt. Gedney for such a purpose was a legal or justifiable act.

How would it be,--independently of the treaty between the United States and Spain,--upon the principles of our government, of the common law, or of the law of nations?.

If a foreign slave vessel, engaged in a traffic which by our laws is denounced as inhuman and piratical, should be captured by the slaves while on her voyage from Africa to Cuba, and they should succeed in reaching our shores, have the constitution or laws of the United States imposed upon our judges, our naval officers, or our executive, the duty of seizing the unhappy fugitives and delivering them up to their oppressors?. Did the people of the United States, whose government is based on the great principles of the revolution, proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence, confer upon the federal executive or judicial tribunals, the power of making our nation accessories to such atrocious violations of human right?

Is there any principle of international law, or law of comity which requires it? Are our Courts bound, and if not, are they at liberty, to give effect here to the slave-trade laws of a foreign nation,--to laws affecting strangers, never domiciled there, when, to give them such effect would be to violate the natural rights of men?

These questions are answered in the negative by all the most approved writers on the laws of nations. 1 Burg. Confl. 741; Story, Confl. 92.

"There exists," says Burge, "a status which is legal in the country in which it is constituted, but illegal in another country to which the person may resort. In this conflict there has been an uniformity of opinion among jurists, and of decisions by judicial tribunals, in giving no effect to the status however legal it may have been in the country in which the person was born, or in which he was previously domiciled if it be not recognized by the law of his actual domicil. This principle was adopted by the Supreme Council of Mechlin as established law in 1531. It refused to issue a warrant to take up a person who had escaped from Spain, where he had been brought and legally held in slavery." Christ. Dec. tom 4. Dec. 80.

By the law of France, the slaves of their colonies, immediately on their arrival in France, become free.

In the case of Forbes vs. Cochrane, 2 Barn. and Cress. 463, this question is elaborately discussed and settled by the English Court of K.B. "The right to slaves," it is there said, "when tolerated by law, is founded not on the law of nature, but on the law of that particular country. It is a law in invitum; and when a party gets out of the power of his master, and gets under the protection of another power, without any wrongful act done by the party giving that protection, the right of the master, which is founded on the municipal law of the particular place only, does not continue. The moment a foreign slave puts his foot on our shores, he ceases to be a slave, because there is no law here which sanctions his being held in slavery. And the local law which held him in slavery against the law of nature has lost its force." 9 Eng. C. L. Rep. 145.

By the law of the State of New York, a foreign slave escaping into that state becomes free. And the Courts of the United States in acting upon the personal rights of men found within the jurisdiction of a free state, are bound to administer the laws as they would be administered by the state courts, in all cases in which the laws of the state do not conflict with the laws or obligations of the United States. The United States as a nation have prohibited the slave trade as inhuman and piratical, and they have no law authorizing the enslaving of its victims. It is a maxim, to use the words of an eminent English judge in the case of Forbes vs. Cochrane, 2 B. and C., "that what is called comitas inter communitates, cannot prevail in any case, where it violates the law of our own country, the law of nature, or the law of God." 9 Eng. C. L.R. 149. And that the laws of a nation proprio vigore have no force beyond its own territories, except so far as it respects its own citizens, who owe it allegiance, is too familiarly settled to need the citation of authorities. See 9 Wheaton, 366; Apollon, 2 Mason, 151--8. The rules on this subject adopted in the English Court of Admiralty are the same which prevail in their courts of common law, though they have decided in the case of the Louis (2 Dodson, 238) as the Supreme Court did in the case of the Antelope, (10 Wheat. 66,) that as the slave trade was not, at that time, prohibited by the law of nations, if a foreign slaver was captured by an English ship, it was a wrongful act, which it would be the duty of the Court of Admiralty to repair by restoring the possession. The principle of amoveas manus, adopted in these cases, has no application to the case of fugitives from slavery.

In this case the wrongful act was done to the Africans, by the seizure of them by Lt. Gedney without warrant or authority. An officer of the United States is not invested with the power of seizing the person of a citizen or a stranger, unless he has committed some crime for which he is liable to be punished by the Courts of the United States. See Doc. 199. H. Rep. 26 Cong. 1 sess. p. 57. (Mr. Wirt's opinion as Attorney General in the case of Manning.) The principle adopted in the cases of the Louis and the Antelope would require the restoration, if not of the property in their possession, at least of their liberty, to the Africans, who were in the exercise, when seized, of their rights as freemen. Certainly it does not warrant their delivery by the Courts of the United States as property to their captive Spaniards.

But it is claimed that if these Africans, though "recently imported into Cuba," were by the laws of Spain the property of Ruiz and Montez, the Government of the United States is bound by the treaty to restore them; and that, therefore, the intervention of the Executive in these proceeding is proper for that purpose. It has already, it is believed, been shown that even if the case were within the treaty, the intervention of the Executive as a party before the judicial tribunals was unnecessary and improper, since the treaty provides for its own execution by the courts on the application of the parties in interest. And such a resort is expressly provided in the 20th Article of the Treaty of 1794 with Great Britain, and in the 26th Article of the Treaty of 1801 with the French Republic, both of which are in other respects similar to the 9th Article of the Spanish Treaty, on which the Attorney General has principally relied.

The 6th Article of the Spanish Treaty has received a judicial construction in the case of the Santissima Trinidad, (7 Wheat. 284,) where it was decided that the obligation assumed is simply that of protecting belligerent vessels from capture within our jurisdiction. It can have no application therefore to a case like the present.

The 9th Article of that treaty provides "that all ships and merchandise of what nature soever, which shall be rescued out of the hands of pirates or robbers, on the high seas, shall be brought into some port of either state, and shall be delivered to the custody of the officers of that port, in order to be taken care of, and restored entire to the true proprietors, as soon as due and sufficient proof shall be made concerning the property thereof."

To render this clause of the treaty applicable to the case under consideration, it must be assumed that under the term "merchandise" the contracting parties intended to include slaves; and that slaves, themselves the recent victims of piracy, who, by a successful revolt, have achieved their deliverance from slavery, on the high seas, and have availed themselves of the means of escape of which they have thus acquired the possession, are to be deemed "pirates and robbers" "from whose hands" such "merchandise has been rescued."

It is believed that such a construction of the words of the treaty is not in accordance with the rules of interpretation which ought to govern our courts; and that when there is no special reference to human beings as property,--who are not acknowledged as such by the law or comity of nations generally, but only by the municipal laws of the particular nations which tolerate slavery, it cannot be presumed that the contracting parties intended to include them under the general term "merchandise." As has already been remarked, it may well be doubted whether such a stipulation would be within the treaty making power of the United States. It is to be remembered that the Government of the United States is based on the principles promulgated in the Declaration of Independence by the Congress of 1776; "that all men are created equal;--that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights,--that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; and that to secure these rights governments are instituted."

The Convention which formed the Federal Constitution, though they recognized slavery as existing in regard to persons held to labor by the laws of the States which tolerated it, were careful to exclude from that instrument every expression that might be construed into an admission that there could be property in men. It appears by the report of the proceedings of the Convention, (3 Madison Papers, 1428), that the first Clause of Section 9, Article 1, which provides for the imposition of a tax or duty on the importation of such persons as any of the States then existing might think proper to admit, &c., "not exceeding ten dollars for each person," was adopted in its present form, in consequence of the opposition by Roger Sherman and James Madison to the clause as it was originally reported, on the ground "that it admitted that there could be property in men;" an idea which Mr. Madison said "he thought it wrong to admit in the Constitution." The words reported by the committee, and stricken out on this objection were: "a tax or duty may be imposed on such migration or importation at a rate not exceeding the average of the duties laid upon imports." The Constitution as it now stands will be searched in vain for an expression recognizing human beings as merchandise or legitimate subjects of commerce. In the case of New York vs. Miln, 11 Peters, 104, 136, Judge Barbour, in giving the opinion of the court, expressly declares, in reference to the power "to regulate commerce" conferred on Congress by the Constitution, that "persons are not the subjects of commerce." Judging from the public sentiment which prevailed at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, it is probable that the first act of the government in the exercise of its power to regulate commerce, would have been to prohibit the slave trade, if it had not been restrained until 1808, from prohibiting the importation of such persons as any of the States, then existing, should think proper to admit. But could Congress have passed an act authorizing the importation of slaves as articles of commerce, into any State in opposition to a law of the state, prohibiting their introduction? If they could, they may now force slavery into every state. For no state can prohibit the introduction of legitimate objects of foreign commerce, when authorized by Congress.

In the construction of all general terms used in the laws of United States, or in treaties to which they may be parties, the fundamental principles of the government and people of the United States, in their collective capacity as a nation, as set forth in their Declaration of Independence to the world, are to be applied, unless the law of nations requires a different interpretation. See Vattel, B II. CXVII. § 271. 280. 300. 302. 307-8-11. In the case of Arredondo, 6 Peters 710, the Supreme Court say: "by the stipulations of a treaty are to be understood its language and apparent intention manifested in the instrument with a reference to the contracting parties, the subject matter, and persons on whom it is to operate."

The United States must be regarded as comprehending free States as well as slave States:--States which do not recognize slaves as property, as well as States which do so regard them. When all speak as a nation, general expressions ought to be construed to mean what all understand to be included in them; at all events, what may be included consistently with the law of nature.

The 9th article of the Spanish Treaty was copied from the 16th article of the Treaty with France, concluded in 1778, in the midst of the war of the Revolution, in which the great principles of liberty proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence were vindicated by our fathers.

By "merchandise rescued from pirates," the contracting parties must have had in view property, which it would be the duty of the public ships of the United States to rescue from its unlawful possessors. Because if it is taken from those who are rightfully in possession, the capture would be wrongful, and it would be our duty to restore it. But is it a duty which our naval officers owe to a nation tolerating the slave-trade, to subdue for their kidnappers the revolted victims of their cruelty?. Could the people of the United States, consistently with their principles as a nation, have ever consented to a treaty stipulation which would impose such a duty on our naval officers?--a duty which would drive every citizen of a free State from the service of his country? Has our Government, which has been so cautious as not to oblige itself to surrender the most atrocious criminals, who have sought an asylum in the United States, bound itself under the term "merchandise," to seize and surrender fugitive slaves?

The subject of the delivery of fugitives was under consideration before and during the negotiation of the Treaty of San Lorenzo; and was purposely omitted in the Treaty. Sec. 10 Waite's State Papers, 151, 433. Our Treaties with Tunis and Algiers contain similar expressions, in which both parties stipulate for the protection of the property of the subjects of each within the jurisdiction of the other. The Algerine regarded his Spanish captive as property; but was it ever supposed that if an Algerine corsair should be seized by the captive slaves on hoard of her, it would be the duty of our naval officers or our Courts of Admiralty to re-capture and restore them?

The phraseology of the entire article in the Treaty, clearly shows that it was intended to apply only to inanimate thing's, or irrational animals; such as are universally regarded as property. It is "merchandise rescued from the hands of pirates and robbers on the high seas" that is to be restored. There is no provision for the surrender of the pirates themselves. And the reason is, because the article has reference only to those who are "hostes humani generis," whom it is lawful for, and the duty of all nations to capture and to punish. If these Africans were "pirates" or sea robbers, whom our naval officers might lawfully seize, it would be our duty to detain them for punishment; and then what would become of the "merchandize?"

But they were not pirates, nor in any sense hostes humani generis. Cinque, the master-spirit who guided them, had a single object in view. That object was--not piracy or robbery--but the deliverance of himself and his companions in suffering, from unlawful bondage. They owed no allegiance to Spain. They were on board of the Amistad by constraint. Their object was to free themselves from the fetters that bound them, in order that they might return to their kindred and their home. In so doing they were guilty of no crime, for which they could be held responsible as pirates. See Bee's Rep. 273. Suppose they had been impressed American seamen, who had regained their liberty in a similar manner, would they in that case have been deemed guilty of piracy and murder? Not in the opinion of Chief Justice Marshall. In his celebrated speech in justification of the surrender by President Adams of Nash under the British Treaty, he says: "Had Thomas Nash been an impressed American, the homicide on board the Hermoine would most certainly not have been murder. The act of impressing an American is an act of lawless violence. The confinement on board a vessel is a continuation of that violence, and an additional outrage. Death committed within the United States in resisting such violence would not have been murder." Bee's Rep. 290.

The United States, as a nation, is to be regarded as a free State. And all men being presumptively frees when "merchandise" is spoken of in the Treaty of a free State, it cannot be presumed that human beings are intended to be included as such. Hence, whenever our Government have intended to speak of heroes as property in their Treaties, they have been specifically mentioned, as in the Treaties with Great Britain of 1783 and 1814. It was on the same principle that Judge Drayton, of South Carolina, decided in the case of Almeida, who had captured during the last war an English vessel with slaves, that the word "property" in the prize act, did not include negroes, and that they must be regarded as prisoners of war, and not sold or distributed as merchandise. 5 Hall's Law Journal, 459.

And it was for the same reason that it was deemed necessary in the Constitution, to insert an express stipulation in regard to fugitives from service. The law of comity would have obliged each State to protect and restore property belonging to a citizen of another, without such a stipulation; but it would not have required the restoration of fugitive slaves from a sister State, unless they had been expressly mentioned.

In the interpretation of Treaties we ought always to give such a construction to the words as is most consistent with the customary use of language;--most suitable to the subject, and to the legitimate powers of the contracting parties;--most conformable to the declared principles of the Government;--such a construction as will not lead to injustice to others, or in any way violate the laws of nature.

These are in substance the rules of interpretation as given by Vattel, B. II. ch. 17. The construction claimed in behalf of the Spanish libellants, in the present case, is at war with them all.

It would be singular, indeed, if the tribunals of a Government which has declared the slave-trade, piracy, and has bound itself by a solemn Treaty with Great Britain, in 1814, to make continued efforts "to promote its entire abolition, as a traffic irreconcilable with the principles of humanity and justice," should construe the general expressions of a Treaty which since that period has been revised by the contracting parties, as obliging this nation to commit the injustice of treating as property the recent victims of this horrid traffic; more especially when it is borne in mind, that the Government of Spain, anterior to the revision of the Treaty in 1819, had formally notified our Government that Africans were no longer the legitimate objects of trade; with a declaration that "His Majesty felt confident that a measure so completely in harmony with the sentiments of this Government, and all of the inhabitants of this Republic, could not fail to be equally agreeable to the President." Doc. 48. 2 Ses. 16 Cong. p. 8.

Would the people of the United States in 1819, have assented to such a Treaty? Would it not have furnished just ground of complaint by Great Britain, as a violation of the 10th article of the Treaty of Ghent?

But even if the Treaty in its terms were such as to oblige us to violate towards strangers the immutable laws of Justice, it would, according to Vattel, impose no obligation. Vattel c. 1, § 9; B. II. c 12, § 161; c. 17, § 311.

The law of nature and the law of nations, bind us as effectually to render justice to the African, as the Treaty can to the Spaniard. Before a foreign tribunal, the parties litigating the question of freedom or slavery, stand on equal ground. And in a case like this, where it is admitted that the Africans were recently imported, and consequently never domiciled in Cuba, and owe no allegiance to its laws, their rights are to be determined by that law which is of universal obligation,--the law of Nature.

If, indeed, the vessel in which they sailed had been driven upon our coast by stress of weather or other unavoidable cause, and they had arrived here in the actual possession of their alledged owners, and had been slaves by the law of the country from which they sailed, and where they were domiciled, it would have been a very different question, whether the Courts of the United States could interfere to liberate them, as was done at Bermuda by the Colonial tribunal in the case of the Enterprize.

But in this case there has been no possession of these Africans by their claimants within our jurisdiction, of which they have been deprived, by the act of our GoVernment or its officers; and neither by the law of comity, or by force of the Treaty, are the officers or Courts of the United States required, or by the principles of our Government permitted to become actors in reducing them to slavery.

These preliminary questions have been made on account of the important principles involved in them, and not from any unwillingness to meet the question between the Africans and their claimants upon the facts in evidence, and on those alone, to vindicate their claims to freedom.

Suppose then, the case to be properly here:--and that Ruiz and Montez, unprejudiced by the decree of the Court below, were at liberty to take issue with the Africans upon their answer, and to call upon this court to determine the question of liberty or property, how stands the case on the evidence before the Court?

The Africans, when found by Lieutenant Gedney, were in a free State, where all men are presumed to be free, and were in the actual condition of freemen. The burthen of proof, therefore, rests on those who assert them to be slaves. 10 Wheaton, 66; 2 Mason, 459. When they call on the Courts of the United States to reduce to slavery men who are apparently free, they must show some law, having force in the place where they were taken, which makes them slaves; or that the claimants are entitled in our courts to have some foreign law,--obligatory on the Africans as well as on the claimants,--enforced in respect to them; and that by such foreign law they are slaves.

It is not pretended that there was any law existing in the place where they were found, which made them slaves, but it is claimed that by the laws of Cuba they were slaves to Ruiz and Montez, and that those laws are to be here enforced. But before the laws of Cuba, if any such there be, can be applied to affect the personal status of individuals within a foreign jurisdiction, it is very clear that it must be shown that they were domiciled in Cuba.

It is admitted and proved in this case that these negroes are natives of Africa, and recently imported into Cuba. Their domicil of origin is consequently the place of their birth in Africa. And the presumption of law is, always, that the domicil of origin, is retained until the change is proved. 1 Burge's Conflict. 34. The burthen of proving the change is cast on him who alledges it. 5 Vesey, 787.

The domicil of origin prevails until the party has not only acquired another, but has manifested and carried into execution, an intention of abandoning his former domicil, and acquiring another, as his sole domicil. As it is the will, or intention of the party which alone determines what is the real place of domicil, which he has chosen, it follows that a former domicil is not abandoned by residence in another, if that residence be not voluntarily chosen. Those who are in exile, or in prison, as they are never presumed to have abandoned all hope of return, retain their former domicil. 1 Burg. 46. That these victims of fraud and piracy,--husbands torn from their wives and families,--children from their parents and kindred,--neither intended to abandon the land of their nativity, nor had lost all hope of recovering it, sufficiently appears from the facts on this record. It cannot surely be claimed that a residence under such circumstances, of these helpless beings for ten days in a slave barracoon before they were transferred to the Amistad, changed their native domicil for that of Cuba.

It is not only incumbent on the claimants to prove that the Africans are domiciled in Cuba, and subject to its laws, but they must show that some law existed there by which "recently imported Africans" can be lawfully held in slavery. Such a law is not to be presumed, but the contrary. Comity would seem to require of us to presume that a traffic so abhorrent to the feelings of the whole civilized world is not lawful in Cuba. These respondents having been born free, and having been recently imported into Cuba, have a right to be everywhere regarded as free, until some law obligatory on them is produced authorizing their enslavement. Neither the law of nature, nor the law of nations authorizes the slave-trade, although it was holden in the case of the Antelope that the law of nations did not at that time, actually prohibit it. If they are slaves then, it must be by reason of some positive law of Spain existing at the time of their recent importation. No such law is exhibited. On the contrary it is proved by the deposition of Dr. Madden, one of the British commissioners resident at Havana, that since the year 1820 there has been no such law in force there either statute or common law.

But we do not rest the case here. We are willing to assume the burthen of proof. On the 14th of May, 1818, the Spanish Government by their minister announced to the Government of the United States that the slave trade was prohibited by Spain; and by express command of the King of Spain, Don Onis communicated to the President of the United States the Treaty with Great Britain of September 23d, 1817, by which the King of Spain, moved partly by motives of humanity, and partly in consideration of 400,000 pounds sterling, paid to him by the British Government for the accomplishment of so desirable an object, engaged that the slave trade should be abolished throughout the dominions of Spain, on the 30th of May, 1820. By the ordinance of the King of Spain of December, 1817, it is directed that every African imported into any of the colonies of Spain in violation of the treaty, shall be declared free in the first port at which he shall arrive.

By the treaty between Great Britain and Spain of the 28th of June, 1835, which is declared to be made for the purpose of "rendering the means taken for abolishing the inhuman traffic in slaves more effective," and to be in the spirit of the treaty contracted between both powers on the 23d of September, 1817, "the slave trade is again declared on the part of Spain to be henceforward totally and finally abolished, in all parts of the world." And by the royal ordinance of November 2d, 1838, the Governor and the naval officers having command on the coast of Cuba, are stimulated to greater vigilance to suppress it.

Such then being the laws in force in all the dominions of Spain, and such the conceded facts in regard to the nativity and recent importation of these Africans, upon what plausible ground can it be claimed by the Government of the United States, that they were slaves in the island of Cuba, and are here to be treated as property, and not as human beings?

The only evidence exhibited to prove them slaves are the papers of the Amistad, giving to Jose Ruiz permission to transport 49 Ladinos belonging to him from Havana to Puerto Principe; and a like permit to Pedro Montez to transport three Ladinos. For one of the four Africans, claimed by Montez (the boy Ka-le) there is no permit at all.

These permits or passports are in the printed custom-house form, which are evidently prepared for the purpose of giving a particular description of the individuals for whom they are intended. But in both, the column left for that purpose, remains a blank. Neither of them contains any description of the individuals, except that they are called by certain Spanish names, to which it appears by the marshal's return, these Africans do not answer, and by which they have never been known.

The papers therefore do not make a prima facie case against them. They are neither individually identified, nor do they collectively answer the description of the persons whom Ruiz and Montez were authorized to transport.

The permits were for Ladinos,--a term exclusively applied to Africans long resident in the island,--acclimated, and familiar with the language of the country. As the African slave trade has been prohibited since 1820, it is legally applicable only to Africans who were imported prior to that time, and according to the deposition of Dr. Madden, it is so customarily used, and understood in Havana.

But the Africans of the Amistad are bozals, and not Ladinos:--a fact which is not only proved by the testimony of the witnesses, but is distinctly admitted on the record, in the admission "that they are natives of Africa and recently imported into Cuba."

Such papers, given on the simple application of the party requesting them, and payment of the customary fees--(see the deposition of Dr. Madden)--given without any notice to, or hearing of the Africans who are claimed to be affected by them, could never be conclusive upon the rights of strangers, even if no fraud was proved, and they were actually described in the permits. See 9 Cranch. 126, 142; 1 Peters, C. C. Rep. 74. Indeed such papers are never regarded by foreign tribunals as conclusive upon anybody. 1 Rob. Adm. 212; 6 Wheat. 1; the Isabella.

The claim that they are so, in the present case, is preposterous, and discreditable to the Government of Spain, by whose minister it is urged.

These Africans were not only "recently imported," but Ruiz and Montez knew it, when they obtained their permits for Ladinos. When Ruiz was inquired of, in New London, whether the negroes could speak Spanish? he replied: "No. They are just from Africa." And the same fact must have been equally well known to Montez in regard to the four little children claimed by him.

The inference then is irresistible, either that they concealed the fact, fraudulently, from the custom-house officer who granted the permits, and falsely represented the negroes whom they intended to ship, to be Ladinos; or that the custom-house officer, knowing the truth, gave them a false certificate, and was himself a party to the fraud. Which alternative does comity to Spain require us to adopt?

To entitle even a foreign judgment to respect as prima facie evidence of a right, it is indispensable to establish "that the Court pronouncing it had a lawful jurisdiction over the cause and the parties. If its jurisdiction fails as to either, it is treated as a nullity, having no obligation, and entitled to no respect, beyond the domestic tribunals. Story's Confl. § 539, 546. And fraud will vitiate any judgment, however well founded in point of jurisdiction. See 15 Johns. 145; 3 Coke, 77.

In regard to judgments in personam, it is holden by the most approved writers on public law "that no sovereign is bound by the jure gentium, to execute a foreign judgment within his dominions. He is at liberty to examine into the merits of the judgment, and refuse to give effect to it, if, upon such examination, it should appear to be unjust or unfounded." Story's Confl. 500. The jurisdiction of the Court may be inquired into, and its power over the parties and things: and the judgment may be impeached for fraud. Ib.

Against a stranger, not domiciled in the country where such judgment is rendered, it is never held to be conclusive when attempted to be executed abroad. 1 Boull. 606; Story's Confl. ub. sup.

But in this case there has been no proceeding against these Africans in Havana; no judgment, or any process against them by which they were declared to be slaves; no investigation of any facts whatever in regard to them, to which they can be deemed to have been, in any sense, parties. Indeed the permits given to Ruiz and Montez were not in fact given for any such purpose as that for which they are attempted to be used. They were given for Ladinos, whom alone,--of native Africans,--it was lawful to hold or transport as slaves. They were obtained without a description of individuals, for the fraudulent purpose of using them to cover bozals, or newly imported Africans, which these are conceded to be. The permits would answer for any other equal number of Africans, just as well as for these.

The object of the deceit practiced by Ruiz and Montez is apparent from the deposition of Dr. Madden. To effect that object a double fraud became necessary. The custom-house permits were obtained by representing the Africans as Ladinos; while to avoid the danger of British cruisers, by whom they would at once be recognized as bozals, they were entered in the license of the schooner, by the commandancia of the port, as "passengers for the Government."

It has been said in an official opinion by the late Attorney-General, (Mr. Grundy), that "as this vessel cleared out from one Spanish port to another Spanish port, with papers regularly authenticated by the proper officers at Havana, evidencing that these heroes were slaves, and that the destination of the vessel was to another Spanish port, the Government of the United States would not be authorized to go into an investigation for the purpose of ascertaining whether the facts stated in those papers by the Spanish officers are true or not;"--"that if it were to permit itself to go behind the papers of the schooner Amistad, it would place itself in the embarrassing condition of judging upon Spanish laws, their force, effect, and application to the case under consideration." In support of this opinion a reference is made to the opinion of this Court in the case of Arredondo, 6 Pet. 729, where it is stated to be "an universal principle that where power or jurisdiction is delegated to any public officer or tribunal over a subject matter, and its exercise is confided to his or their discretion, the acts so done are binding and valid as to the subject matter; and individual rights will not be disturbed collaterally for any thing done in the exercise of that discretion within the authority conferred. The only questions which can arise between an individual claiming a right under the acts done, and the public, or any person denying its validity, are power in the officer, and fraud in the party."

The principle thus stated was applicable to the case then before the Court, which related to the validity of a grant made by a public officer; but it does not tend to support the position for which it is cited in the present case. For in the first place there was no jurisdiction over these newly imported Africans, by the laws of Spain, to make them slaves, any more than if they had been white men. The ordinance of the king declared them free: Secondly, there was no intentional exercise of jurisdiction over them for such a purpose by the officer who granted the permits; and 3dly, the permits were fraudulently obtained, and fraudulently used by the parties claiming to take benefit of them. For the purposes for which they are attempted to be applied, the permits are as inoperative as would be a grant from a public officer, fraudulently obtained, where the State had no title to the thing granted, and the officer no authority to issue the grant. See 6 Pet. R. 730; 5 Wheat. 303.

But it is said, we have no right to place ourselves in the position of judging upon the Spanish laws. How can our Courts do otherwise; when Spanish subjects call upon them to enforce rights which, if they exist at all, must exist by force of Spanish laws? For what purpose did the Government of Spain communicate to the Government of the United States, the fact of the prohibition of the slave trades unless it was that it might be known and acted upon by our Courts? Suppose the permits to Ruiz and Montez had been granted for the express purpose of consigning to perpetual slavery these recent victims of this exhibited trade, could the Government of Spain now as the or the Courts of the United States to give validity colonial officer, in direct violation of that prohibition; us aiders and abettors in what we know to be an atrocious.

It may be admitted that, even after such an annunciation, could not lawfully seize a Spanish slaver, cleared out as such, by the Governor of Cuba: but if the Africans on board of her could effect their own deliverance, and reach our shores, has not the Government of Spain authorized us to treat them with hospitality as freemen? the Spanish minister, without offence, ask the Government of the States to seize these victims of fraud and felony, and treat them as property, because a colonial governor had thought proper to violate the ordinance of his king, in granting a permit to a slaver?

But in this case we make no charge upon the Governor of Cuba: A fraud upon him is proved to have been practiced by Ruiz and Montez. He never undertook to assume jurisdiction over these Africans as slaves, or to decide any question in regard to them. He simply issued, on the application of Ruiz and Montez, passports for Ladino slaves from Havana to Puerto Principe. When under color of those passports, they fraudulently put on board the Amistad, bozals, who, by the laws of Spain, could not be slaves, we surely manifest no disrespect to the acts of the Governor, by giving efficacy to the laws of Spain, and denying to Ruiz and Montez the benefit of their fraud. The custom-house license, to which the name of Espeleta in print was appended, was not a document given or intended to be used as evidence of property between Ruiz and Montez and the Africans; any more than a permit from our custom-house would be to settle conflicting claims of ownership to the articles contained in the manifest. As between the government and the shippers, it would be evidence if the negroes described in the passport were actually put on board, and were in truth the property of Ruiz and Montez, that they were legally shipped:--that the custom-house forms had been complied with; and nothing more. But in view of the facts as they appear, and are admitted in the present case, the passports seem to have been obtained by Ruiz and Montez, only as a part of the necessary machinery for the completion of a slave voyage. The evidence tends strongly to prove that Ruiz at least, was concerned in the importation of these Africans, and that the re-shipment of them under color of passports obtained for Ladinos as the property of Ruiz and Montez, in connection with the false representation on the papers of the schooner, they were "passengers for the Government," was an artifice these slave-traders for the double purpose of evading the cruisers, and legalizing the transfer of their victims to ultimate destination. It is a remarkable circumstance, more than a year has elapsed, since the decree of the denying the title of Ruiz and Montez, and pronouncing the Africans free, not a particle of evidence has since been produced in support of their claims. And yet,--strange as it may seem,--during all this time, not only the sympathies of the Spanish minister, but the of our own Government have been enlisted in their behalf!