Speech Excerpt from the Cornerstone Laying Ceremony for the Yorktown Monument

Excerpt from the address of Robert C. Winthrop during the cornerstone laying ceremony for the Yorktown Monument on October 19, 1881.

ORATION.

MR. PRESIDENT AND FELLOW-CITIZENS OF THE UNITED STATES: I am profoundly sensible of the honor of being called to take so distinguished a part in this great Commemoration, and most deeply grateful to those who have thought me worthy of such an honor. But it was no affectation when, in accepting the invitation of the Joint Committee of Congress, I replied that I was sincerely conscious of my own insufficiency for so high a service. Aud if I felt, as I could not fail to feel, a painful sense of inadequacy at that moment, when the service was still a great way off, how much more must I be oppressed and overwhelmed by it now, in the immediate presence of the occasion! As I look back to the men with whom I have been associated in my own Commonwealth-Choate, Everett, Webster, to name no others—I may well feel that I am here only by the accident of survival.

But I cannot forget that I stand on the soil of Virginia—a State which, of all others in our Union, has never needed to borrow an orator for any occasion, however important or exacting. Her George Mason and Thomas Jefferson, her James Madison and John Marshall, were destined, it is true, to render themselves immortal by their pens, rather than by their tongues. The pens which drafted the Virginia Bill of Rights, the Declaration of American Independence, and so much of the text, the history, the vindication, and the true construction of the American Constitution, need fear comparison with none which have ever been the implements of human thought and language. But from her peerless Patrick Henry, through the long succession of statesmen and patriots who have illustrated her annals, down to the recent day of her Rives, her McDowell, and her Grigsby—all of whom I have been privileged to count among my personal friends— Virginia has bad orators enough for every emergency, at the Capitol or at home. She has them still. And yet I hazard nothing in saying that the foremost of them all would have agreed with me, at this hour, that the theme and the theater are above the reach of the highest art; and would be heard exclaiming with me, in the words of a great Roman poet, “Unde ingenium par materiæ ?” whence, whence shall come a faculty equal to the subject? For myself, I turn humbly and reverently to the only Source from which such inspiration can be invoked!

Certainly, fellow-citizens, had I felt at liberty to regard the invitation as any mere personal compliment, supremely as I should have prized it, I might have hesitated about accepting it much longer than I did hesitate. But when I reflected on it as at least including a compliment to the old Commonwealth of which I am a loyal son—when I reflected that my performance of such a service might help, in ever so slight a degree, to bring back Virginia and Massachusetts, even for a day-would that it might be forever!—into those old relations of mutual'amity and good nature and affection which existed in the days of our Fathers, and without which there could have been no surrender here at Yorktown to be commemorated—10 Union, no Independence, no Constitution—I could not find it in my heart for an instant to de. cline the call. Never, never could I shrink from any service, however arduous, or however perilous to my own reputation, which might haply add a single new link, or even strengthen and brighten an old link, in that chain of love, which it has been the prayer of my life might hind together in peace and goodwill, in all time to come, not only. New England and the Old Dominion, but the whole North and the whole South, for the best welfare of our common Country, and for the best interests of Liberty throughout the world!

Not the less, however, have I come here today in faint hope of being able to meet the expectations and demands of the occasion. For, indeed, there are occasions which no man can fully meet, either to the satisfaction of others or of himself-occasions which seem to scorn and defy all utterance of human lips, whose complicated emotions and incidents cannot be compressed within the little compass of a discourse; whose far-reaching relations and world-wide influences refuse to be narrowed and condensed into any formal sentences or paragraphs or pages; occasions when the booming cannon, the rolling drum, the swelling trumpet, the cheers of multitudes, and the solemn Te Deums of churches and cathedrals, afford the only adequate expression of the feelings, which their mere contemplation, even at the end of a century, cannot fail to kindle.'

Yet, if it be not in me, at an age which might fairly have exempted me altogether from such an effort, to do full justice to the grand assembly and the grander topics before me, it certainly is in me, my friends, to breathe out from a full heart the congratulations which belong to this hour; to recall briefly some of the momentous incidents we are here to commemorate; to sketch rapidly some of the great scenes which gave such imperishable glory to yonder bay and river, and their historic banks; to name with honor a few, at least, of the illustrious men connected with those scenes, and, above all and before all, to give some feeble voice to the gratitude which must swell and fill and overflow every American breast to-day towards that generous and gallant nation across the sea, represented here at this moment by so many distinguished sons of so many endeared and illustrious names, which helped us so signally and so decisively at the most critical point of our struggle, in vindicating our rights and liberties, and in achieving our national Independence.

Yes, it is mine, and somewhat peculiarly mine, perhaps, notwithstanding the presence of the official representatives of my native State, to bear the greetings of Plymouth Rock to Jamestown; of Bunker Hill to Yorktown; of Boston, recovered from the British forces in '76, to Mount Vernon, the home in life and death of her illustrious deliverer; and there is no office within the gift of Congresses, Presidents, or People, which I could discharge more cordially and fervently. And may I not hope, as one who is proud to feel coursing in his veins the Huguenot blood of a Massachusetts patriot who enjoyed the most affectionate relations with the young La Fayette when he first led the way to our assistance; as one, too, who has personally felt the warm pressure of his own hand and received a benediction from his own lips, under a father and a mother's roof, nearly threescore years ago, when he was the guest of the nation; and, let me add, as an old presiding officer in that representative chamber at the Capitol, where, side by side with that of Washington, its only fit companion-piece, the admirable full-length portrait of the Marquis, the work and the gift of his friend Ary Scheffer, was so long a daily and hourly feast for my eyes and inspiration for my efforts—may I not hope that I shall not be regarded as a wholly unfit or inappropriate organ of that profound sense of obligation and indebtedness to La Fayette, to Roclambeau, to De Grasse, and to France, which is felt and cherished by us all at this hour ?

For, indeed, fellow-citizens, our earliest and our latest acknowledgments are due this day to France, for the inestimable services which gave us the crowning victory of the 19th of October, 1781. It matters not for us to speculate now whether American Independence might not have been ultimately achieved without her aid. It matters not for us to calculate or conjecture how soon, or when, or under what circumstances that grand result might have been accomplished. We all know that, God willing, such a consummation was as certain in the end as tomorrow's sunrise, and that no earthly potentates or powers, single or conjoined, could have carried us back into a permanent condition of colonial dependence and subjugation. From the first bloodshed at Lexington and Concord, from the first battle of Bunker Hill, Great Britain had lost her American Colonies, and their established and recognized independence was only a question of time. Even the surrender of Burgoyne at Saratoga in 1777, the only American battle included by Sir Edward Creasy in his 6 Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World,” of which he says that “no military event can be said to have exercised a more important influence on the future fortunes of mankind," and of which the late Lord Stanhope had said that this surrender “had not merely changed the relation of England and the feelings of Europe towards these insurgent colonies, but had modified, for all times to come, the connection between every Colony and every parent State"-even this most memorable surrender gave only a new assurance of a foregone conclusion, only hastened the march of events to a predestined issue. That march for us was to be ever onward until the goal was reached. However slow or difficult it might prove to be, at one time or at another time, the motto and the spirit of John Hampden were in the minds, and hearts, and wills of all our American patriots– Nulla vestigia retrorsum”-no footsteps backward.

Nor need we be too curious to inquire to-day into any special inducements which France may have had to intervene thus nobly in our behalf, or into any special influences under which her King, and Court, and People, resolved at last to undertake the intervention. We may not forget, indeed, that our own Franklin, the great Bostonian, had long been one of the American Commissioners in Paris, and that the fame of his genius, the skill and adroitness of his negotiations, and the magnetism of his personal character and presence were no secondary or subordinate elements in the results which were accomplished. As was well said of him by a French historian, “ His virtues and his renown negótiated for him; and, before the second year of his mission had expired, no one conceived it possible to refuse fleets and an army to the compatriots of Franklin.” The Treaty of Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance were both eminently Franklin's work, and both were signed by him as early as the 6th of February, 1778. His name and his services are thus never to be omitted or overlooked in connection with the great debt which we owe to France, and which we so gratefully commemorate on this occasion.

But signal as his services were, Franklin cannot be named as standing first in this connection. Nearly two years before his treaties were negotiated and signed, a step had been taken by another than Franklin, which led, directly and indirectly, to all that followed. The young LA FAYETTE, then but nineteen years of age, a captain of the French dragoons, stationed at Metz, at a dinner given by the commandant of the garrison to the Duke of Gloucester, a brother of George III, happened to hear the tidings of our Declaration of Independence, which had reached the Duke that very morning from London. It formed the subject of animated and excited conversation, in which the enthusiastic young soldier took part. And before he had left the table, an inextinguishable spark had been struck and kindled in his breast, and his whole heart was on fire in the cause of American liberty. Regardless of the remonstrances of his friends, of the Ministry, and of the King himself, in spite of every discouragement and obstacle, he soon tears himself away from a young and lovely wife, leaps on board a vessel which he had provided for himself, braves the perils of a voyage across the Atlantic, then swarming with cruisers, reaches Philadelphia by way of Charleston, South Carolina, and so wins at once the regard and confidence of the Continental Congress, by his avowed desire to risk his “life in our service, at his own expense, without pay or allowance of any sort, that on the 31st of July, 1777, before he was yet quite twenty years of age, he was commissioned a Major-General of the Army of the United States.

It is hardly too much to say that from that dinner at Metz and that 31st day of July in Philadelphia, maybe dated the train of influences and events which culminated, four years afterwards, in the surrender of Cornwallis to the Allied Forces of America and France. Presented to our great Virginian commander-in-chief a few days only after his commission was voted by Congress, an intimacy, a friendship, an affection grew up between them almost at sight, which might well-nigh recall the classical loves of Achilles and Patroclus, or of Æneas and Achates. Invited to become a member of his military family, and treated with the tenderness of a son, La Fayette is henceforth to be not only the beloved and trusted associate of Washington, but a living tie between his native and his almost adopted country. Returning to France in January, 1779, after eighteen months of brave and valuable service here, during which he had been wounded at Brandywine, had exhibited signal gallantry and skill while an indignant witness of Charles Lee's disgraceful, if not treacherous, misconduct at Monmouth, and had received the thanks of Congress for important services in Rhode Island, he was now in the way of appealing personally to the French Ministry to send an army and a fleet to our assistance. He did appeal; and the zeal and force of his arguments at length prevailed. Beaumarchais had already done something for us in the way of money; and the amiable and well-meaning Count d'Estaing, at one time a protégè of Voltaire, had, indeed, already made efforts in our behalf with twelve ships of the line and three frigates. Poor Marie Antoinette must not be forgotten as having prompted and procured that assistance. d'Estaing, however, owing in part to the want of wise counsel and co-operation, had accomplished little or nothing for us, and had left our shores to die at last by the guillotine. But now, by the advice and persuasion of La Fayette, the army of Rochambeau, and afterwards the powerful fleet of the Count de Grasse, are to be sent over to join us; and the young Marquis, to whom alone the decision of the King was first communicated as a state secret, hastens back with eager joy to announce the glad “tidings to Washington, and to arrange with him for the reception and employment of the auxiliary forces.

Accordingly, on the 10th of July, 1780, a squadron of ten ships of war, under the unfortunate Admiral de Ternay, brings Rochambeau with six thousand French troops into the harbor of Newport, with instructions - to act under Washington and live with the Americans as their brethren;" and the American officers are forthwith desired by Washington, in general orders, “ to wear white and black cockades as a symbol of affection for their Allies.”

Nearly a full year, however, was to elapse before the rich fruits of that alliance were to be developed—a year of the greatest discouragement and gloom for the American cause. The gallant but vainglorious Gates, whose head had been turned by his success at Saratoga, had now failed disastrously at Camden; and Cornwallis, elated by having vanquished the conqueror of Burgoyne, was instituting a campaign of terror in the Carolinas, with Tarleton and the young Lord Rawdon as the ministers of his rigorous severities, and was counting confidently on the speedy reduction of all the Southern Colonies. Our siege of Savannah had failed to recover it from the British. Charleston, too, bad been forced to capitulate to Clinton. Not the steady conduct and cour. age of Lincoln; not the resolute endurance and heroism of Greene, the great commander of the Southern Department; not the skillful strategy of La Fayette himself in foiling Cornwallis at so many turns and leading him into countless perplexities and pitfalls; not all the chivalry of Sumter and Marion and Pickens; not the noble and generous example of his own Virginia, exposing and almost sacrificing herself for the relief and rescue of her Southern sisters; not even our well-won victories at King's Mountain under Campbell and Shelby, and at the Cowpens under the glorious Morgan, could keep Washington from being disheartened and despondent in looking for any early termination of the cares and responsibilities which weighed upon him so heavily.

The war on our side seemed languishing. The sinews of war were slowly and insufficiently supplied. All the untiring energy and practical wisdom and patriotic self-sacrifice of Robert Morris, the great Financier of the Revolution, without whom the campaign of 1781 could not have been carried along, hardly sufficed to keep our soldiers in food and clothing. Discontents were gathering and growing in the Army, and even its entire dissolution began to be seriously apprehended. A provision that all enlistments should be made to the end of the war, and entitling all officers, who should continue in service to that time, to half-pay for life, did much, for the moment, to reanimate the recruiting system and give new spirits and confidence to the officers. But it was soon found that, in many of the States, enlistments could only be effected for short terms; while the half-pay for life was rendered odious to the people, and, before the war was over, had become the subject of a commutation, which to this hour has been but partially fulfilled, and which calls loudly, even amid these Centennial rejoicings, for equitable consideration and adjustment. The Confederation which was to unite the strength, wealth, and wisdom of all the Colonies in a perpetual Union,” which had been signed by so many of them three years before, and which now, on the 1st of March, 1781, has just received the tardy signature of the last of them, is but miserably fulfilling its promise. Arsenals and magazines, field equipage and means of transportation, and, above all, both men and money, are lamentably wanting for any vigorous offensive campaign. “Scarce any one of the States," says Bancroft, " had as yet sent an eighth part of its quota into the field,” and there was no power in the Confederate Congress to enforce its requisitions. In vain did the young Alexander Hamilton, at only twenty-three years of age, with a precocity which has no parallel but that of the younger Pitt, pour out liessons of political and financial wisdom from the camp, in which he is soon to display such conspicuous valor, arraigning the Confederation as 6 neither fit for war nor peace.” In vain had Washington written to George Mason, not long before, “Un. less there be a material change both in our civil and military policy, it will be useless to contend much longer," following that letter with another, as late as the 9th of April, 1781, to Colonel John Laurens, who had gone on a special mission to Paris, in which he gave this most explicit warning: “If France delays a timely and powerful aid in the critical posture of our affairs, it will avail us nothing should she attempt it hereafter. We are at this hour suspended in the balance... We cannot transport the provisions from the States in which they are assessed to the army, because we cannot pay the teamsters, who will no longer work for certificates. Our troops are approaching fast to nakedness, and we have nothing to clothe them with. Our hospitals are without medicine, and our sick without meat, except such as well men eat. All our public works are at a stand, and the artificers disbanding. In a word, we are at the end of our tether, and now or never our deliverance must come.”

God's holy name be praised, deliverance was to come and did come, now!

Any material change in our civil policy was, indeed, to await the action of civil rulers; but Washington, himself and alone, could happily control our military policy. And he did control it. Within forty days from the date of that emphatic letter to Laurens, on the 18th of May, 1781, Rochambeau, with the Marquis de Chastellux, leaves New. port for Wethersfield, in Connecticut, to hold a conference with Washington at his call. On the 6th of July, the union of the French troops with the American army is completely accomplished at Phillipsburg, ten miles only from the most advanced post of the British in New York, the two armies united making an effective force of at least ten thousand men. On the 8th, Washington has a review of honor of the French troops, Rochambeau having reviewed the American troops on the 7th. On the 19th of August, the united armies commence their march from Phillipsburg, and reach Philadelphia on the 3d of September, where, Congress being in session, the French army, as we are told in the journal of the gallant Count William de Deux-Ponts, “paid it the honors which the King had ordered us to pay.” And in that journal, so curiously rescued from a Paris bookstall on one of the Quais, in 1867,*the Count most humorously adds: “The thirteen members of Congress took off their thirteen hats at each salute of the flags and of the officers; and that is all I have seen that was respectful or remarkable.” Well, that was surely enough. What more could they have done? Virginia herself, even in her earlier, I will not presume to say her better, days of the strictest construction, could not have desired or conceived a more significant and signal homage to the doctrine of State's Rights, than those thirteen bats so ludicrously lifted together at the successive salutes of each French officer and each French flag!

Thus far the destination of the Allied Armies was a secret even to themselves. Certainly, Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander-in chief at New York, was carefully kept in ignorance of Washington’s plan, and was even made to believe that on himself the double bolt was fall. He was, indeed, so sorely outwitted and perplexed that he is found at one moment sending urgent orders to Cornwallis for large detachments of his Southern army; at another moment, promising to send substantial re-enforcements to bim; and at last, making up his mind, too late, to join Cornwallis in person, with as little delay as possible. Meantime, in the hope of creating a diversion, he despatches the infamous Arnold, whose treason had shocked the moral sense of mankind less than a year before, of whom Washington is at this moment writing "that the world is disappointed at not seeing him in gibbets,” and who had just been recalled from an expedition in this very region, where he had burned and pillaged whatever he could lay his hands on, or set his torch to, along yonder James River, to prosecute his nefarious exploits at the North, and strike a parricidal blow upon his native State. Poor New London and the heroic Ledyard are now to pay the penalty of withstanding the audacious traitor, by the burning of their town and the brutal massacre of the garrison and its commander.

But no diversion or interruption of Washington's plans could be affected in that way or in any other way; and at length, those plans are divulged and executed under circumstances which give assurance of success, and which cannot be recalled, even at this late day, without an irrepressible thrill of delight and gratitude.

Felix ille dies, felix et dicitur annus,

Felices, qui talem annum videre, dieinque!

Leaving Philadelphia, with the Army, on the 5th of September, Washington meets an express near Chester, announcing the arrival, in Chesapeake Bay, of the Count de Grasse, with a fleet of twenty-eight ships of the line, and with three thousand five hundred additional French troops, under the command of the Marquis de St. Simon, who had already been landed at Jamestown, with orders to join the Marquis die La Fayette!

" The joy,” says the Count William de Deux-Ponts in his precious journal, “ the joy which this welcome news produces among all the troops, and which penetrates General Washington and the Count de Rochambeau, is more easy to feel than to express.” But, in a foot-pote to that passage, he does express and describes it, in terms which cannot be spared and could not be surpassed, and which adds a new and charming illustration of the emotional side of Washington's nature. "I have been equally surprised and touched,” says the gallant Deux-Ponts,“ at the true and pure joy of General Washington. Of a natural coldness and of a serious and noble approach, which in him is only true dignity, and which adorn so well the chief of a whole nation, his features, his physiognomy, his deportment, all were changed in an instant. He put aside his character as arbiter of North America, and contented himself for a moment with that of a citizen, happy at the good fortune of his country. A child, whose every wish had been gratified, would not have experienced a sensation more lively, and I believe I am doing honor to the feelings of this rare man is endeavoring to express all their ardor.”

Thanks to God, thanks to France, from all our hearts at this hour, for this true and pure joy” which lightened the heart, and at once dispelled the anxieties of our incomparable leader. It may be true that Washington seldom smiled after he had accepted the command of our Revolutionary Army, but it is clear that on that 5th of September he not only smiled but played the boy. The arrival of that magnificent French fleet, with so considerable a re-enforcement of French troops, gave him a relief and a rapture which no natural reserve or official dignity could restrain or conceal, and of which he gave an impulsive manifestation by swinging bis own chapeau in welcoming Rochambeau at the wharf. In Washington's exuberant joy we have a measure, which nothing else could supply, of the value and importance of the timely, succors which awakened it. Thanks, thanks to France, and thanks to God, for vouchsafing to Washington at last that happy day, which his matchless fortitude and patriotism so richly deserved, and which, after so many trials and discouragements, he so greatly needed.

All now went merry," with him, " as a marriage bell.” Under the immediate influence of this joy, which he had returned for a few hours to Philadelphia to communicate in person to Congress, where all the thirteen hats must bare come off again with three times thirteen cheers, and while the Allied Armies are hurrying southward, he makes a hasty trip with Colonel Humphreys to his beloved Mount Vernon and his more beloved wife-his first visit home since he left it for Cambridge in 1775. Rochambeau, with his suite, joins him there on the 10th, and Chastellux and his aids on the 11th; and there, with Mrs. Washington, he dispenses, for two days, “ a princely hospitality” to his foreign guests. But the 13th finds them all on their way to rejoin the Army at Williamsburg, where they arrive on the 15th, “to the great joy of the troops and the people," and where they dine with the Marquis de St. Simon. On the 18th Washington and Rochambeau, with Knox and Chastellųx and Du Portail, and with two of Washington's aids, Colonel Cobb, of Massachusetts, and Colonel Jonathan Trumbull, jr., of Connecticut, embark on the 6 Princess Charlotte” for a visit to the French fleet; and early the next morning they are greeted with “ the grand sight of thirty-two ships of the line”—for De Barras, from Newport, had joined De Grasse, with his four ships, magnanimously waving his own seniority in rank—6 in Lynn Haveu Bay, just under the point of Cape Henry.” They go on board the Admiral's ship-the famous 66 Ville de Paris,” of one hundred and four guns—for a visit of ceremony and consultation, and at their departure, the Count de Grasse mans the yards of the whole fleet and fires salutes from all the ships. A few days more are spent at Williamsburg on their return, where they find General Lincoln already arrived with a part of the troops from the North, having hurried them, as Washington besought him, " on the wings of speed," and where the word is soon given, “ On, on, to York and Gloucester!”

Washington takes his share of the exposure of this march, and the night of the 28th of September finds him, with all his military family, sleeping in an open field within two miles of Yorktown, without any other covering, as the journal of one of his aids states, " than the canopy of the heavens, and the small spreading branches of a tree,” which the writer predicts “ will probably be rendered venerable from this circumstance for a length of time to come.” Yes, venerable, or certainly memorable forever, if it were known to be in existence. You will all agree with me, my friends, that.if that tree which overshadowed Washington sleeping in the open air on his way to Yorktown, were standing today—if it had escaped the necessities and casualties of the siege, and were not cut down for the abatis of a redoubt, or for camp-fires and cooking fires long ago-if it could anyhow be found and identified in yonder Beech Wood or Locust Grove or Carter's Grove —no Wellington Beech or Napoleon Willow, no Milton or even Shakspeare Mulberry, no Oak of William the Conqueror at Windsor, or of Henri IV at Fontainebleau, nor even those historic trees which gave refuge to the fugitive Charles II, or furnished a hiding place for the Charter which he granted to Connecticut on his restoration, would be so precious and so hallowed in all American eyes and hearts to the latest generation.*

Everything now hurries, almost with the rush of a Niagara cataract, to the grand fall of Arbitrary Power in America. Lord Cornwallis had taken post here at Yorktown as early as the 4th of August, after being foiled so often by 6 that boy,” as he called La Fayette, whose Virginia campaign of four months was the most effective preparation for all that was to follow, and who, with singular foresight, perceived at once that his lordship was now fairly entrapped, and wrote to Washington, as early as the 21st of August, that " the British army must be forced to surrender.” Day by day, night by night, that prediction presses forward to its fulfillment. The 1st of October finds our engineers reconnoitering the position and works of the enemy. The 2d witnesses the gallantry of the Duke de Lauzun and his legion in driving back Tarle. ton, whose raids had so long been the terror of Virginia and the Carolinas. On the 6th, the Allied Arinies broke ground for their first parallel, and proceeded to mount their batteries on the 7th and 8th. On the 9th, two batteries were opened—Washington himself applying the torch to the first gun; and on the 10th, three or four more were in play66 silencing the enemy's works, and making,” says the little diary of Colonel Cobb, “most noble music.” On the 11th, the indefatigable Baron Steuben was breaking the ground for our second parallel, within less than four hundred yards of the enemy, which was finished the next morning, and more batteries mounted on the 13th and 14th.

But the great achievement of the siege still awaits its accomplishment. Two formidable British advanced redoubts are blocking the way to any further approach, and they must be stormed. The allied troops divide the danger and the glory between them, and emulate each other in the assault. One of these redoubts is assigned to the French grenadiers and chasseurs, under the general command of the Baron de Viomesnil. The other is assigned to the American light infantry, under the general command of La Fayette. But the detail of special leaders to conduct the two assaults remains to be arranged. Viomesnil readily designates the brave Count William to lead the French storming party, who, though he came off from his victory wounded, counts it “ the happiest day of his life.' A question arises as to the American party, which is soon solved by the impetuous but just demand of our young Alexander Hamilton to lead it. And lead it he did, with an intrepidity, a heroism, and a dash unsurpassed in the whole history of the war. The French troops had the largest redoubt to assail, and were obliged to pause a little for the regular sappers and miners to sweep away the abatis. But Hamilton rushed on to the front of his redoubt, with his right wing led by Colonel Gimat and seconded by Major Nicholas Fish, heedless of all impediments, overleaping palisades and abatis, and scalding the parapets—while the chivalrous John Laurens was taking the garrison in reverse. Both redoubts were soon captured; and these brilliant actions virtually sealed the fate of Cornwallis. 66A small and precipitate sortie,” as Washington calls it, was made by the British on the following evening, resulting in nothing; and the next day a vain at. tempt to evacuate their works, and to escape by crossing over to Gloucester, was defeated by a violent and, for us, down the most providential storm of rain and wind-of which the elements favored us with a Centennial reminiscence last night. Meantime not less than a hundred pieces of our heavy ordnance were in continual operation, and “the whole peninsula trembled under the incessant thunderings of our infernal machines." Would that no machines more truly “ infernal” had brought disgrace on any part of our land in these latter days! But these brought victory at that day. A suspension of hostilities, to arrange terms of capitulation, was proposed by Cornwallis on the 17th; the 18th was occupied at Moore's House in settling those terms; and on the 19th the articles were signed by which the garrison of York and Gloucester, together with all the officers and seamen of the British ships in the Chesapeake, “surrender themselves Prisoners of War to the Combined Forces of America and France.”

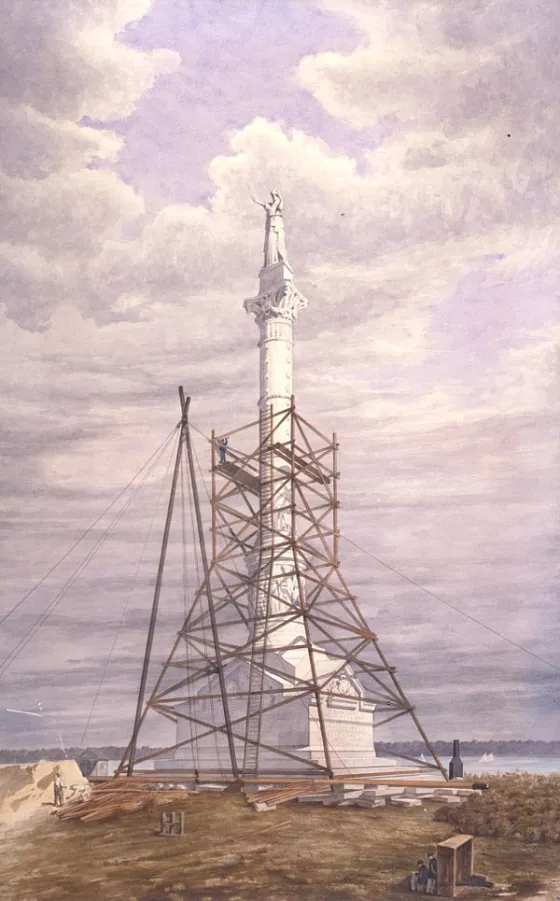

And now, fellow-citizens, there follows a scene than which nothing more unique and picturesque has ever been witnessed on this continent, or anywhere else beneath the sun. Art has essayed in vain to depict it. Trumbull—whose brother, not he himself, was an eye-witness of it as one of Washington's aids—has done his best with it; and his picture in the Rotunda of the Capitol is full of interest and value, giving the portraits of the officers present, as carefully taken by himself from the originals. John Francis Renault, too--assistant secretary of the Count de Grasse, and an engineer of the French Forces—has left us a contemporaneous engraved sketch of it, which has quite as many elements of fancy as of truth. In this engraving, all the officers are ou foot, while Trumbull has rightly put most of them on horseback. Meantime, Renault not only gives Cornwallis surrendering his sword in person, though we all know that he did not leave his quarters on that occasion, but looks forward a full century and exhibits in the background the Column which ought to have been here long ago, but of which the corner-stone was only laid yesterday! a park of artillery, with sappers and miners; and with a large mass of patriotic Virginian militia, collected and commanded by the admirable Governor Nelson. Not quite all the Colonies, perhaps, were represented in force as they had been at Germantown, but hardly any of them were without some representation, individual if not collective many of them in simple, homespun, every-day wear, many of their dresses bearing witness to the long, hard service they had seen-coats out at the elbow, shoes out at the toe, and in some cases no coats, no shoes at all. But the STARS AND STRIPES, which had been raised first at Saratoga, floated proudly above their heads, and no color blindness on that day mistook their tints, misinterpreted their teachings, or failed to recognize the union they betokened and the glory they foreshadowed.

Standing here, however, on the very spot to-day, with the records of history in our hands—as summed up in the brilliant volumes of Baucroft and Irving, or scattered through the writings of Sparks, or spread in detail over the “ Field-Book” of Lossing, or on the more recent pages of Carrington's 6 Battles of the Revolution” and Austin Stevens's American Historical Magazine, not forgetting the precious journals and diaries of Thatcher and Trumbull and Cobb, of Deux-Ponts and the Abbé Robin, and of Washington himself, nor that of the humbler Anspach Sergeant in the Life of Steuben” — we require no aid of art, or even of imagination, to call back, in all its varied and most impressive details, a scene which, as we dip our brush to paint it now at the end of a hundred years, seems almost like a tale of Fairy-Land.

Click here for the rest of the address and the full text of ceremonies

Related Battles

389

8,589