War of 1812: "The city was left a prey to the invaders"

The following account was published in newspapers, giving the perspective of an American soldier on the Battle of Bladensburg and the burning of Washington D.C. in August 1814. Toward the end of paragraph two, there are a number of asterisks; these are in the original and might be a censoring or redaction of opinion or information.

Extract to the Editors of the American—Dated Washington, Aug. 29.

Having been out with the troops during their recent movements, I have not had it in my power to write to you before this time. I now propose to give you a rapid sketch of the campaign, which has so far been disgraced by the destruction of the publick buildings, navy yard, and bridges in this city, and one or two unnecessary, not to say scandalous retreats.

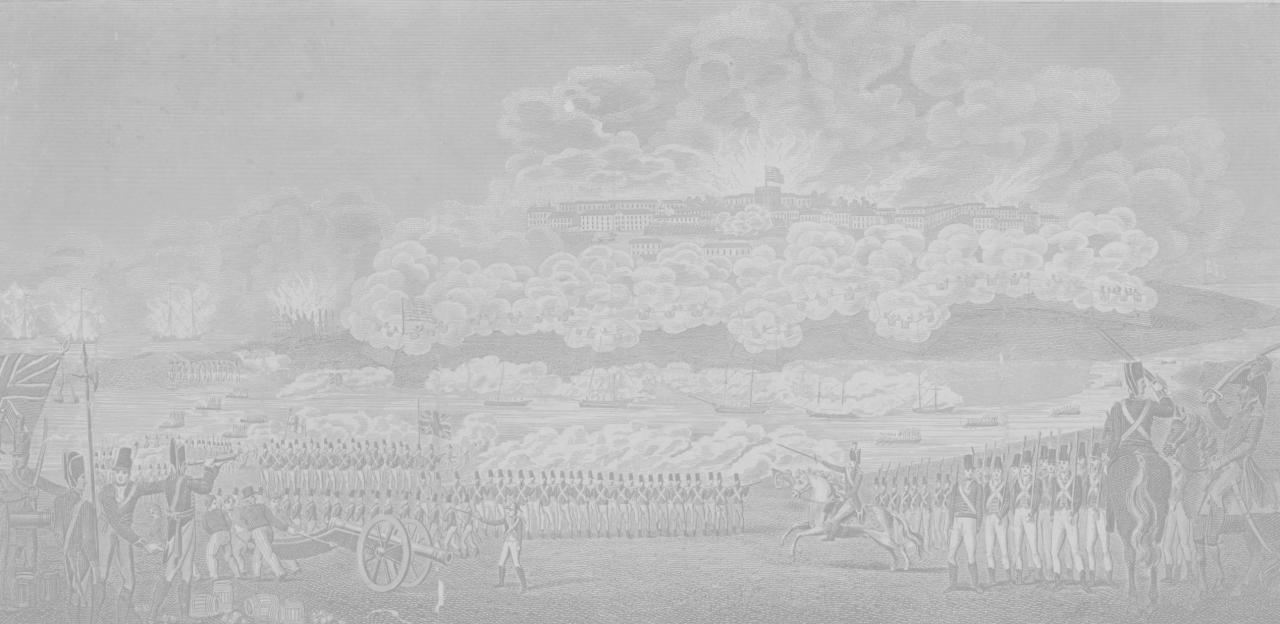

On the 20th inst. the brigade of volunteers and militia of this district, under General Smith, marched toward the Patuxent; on Sunday 21st they reached the Wood Yard 16 miles hence. On Monday morning, Peter's artillery, Davidson's infantry, to which I belong, and Stull's riflemen, forming the advance guard marched to meet the enemy, then on their way from Nottingham for the city; about ten o'clock we found the cavalry and the 36th regiment of U.S. regulars on the retreat. At the suggestion of major Peter, who commanded our advanced guard, but who had no control over the regulars, we were all formed for action; but general Winder, who had gone on ahead, returned and ordered us to retreat, the enemy being with in a mile and a half of us. Our officers said it was a precipitate retreat, and I thought so too. We could have checked the enemy. On our retreat we learnt that the British had taken the road to Upper Marlborough; and we heard Barney's flotilla blown up. We returned to the cross road leading to Bladensburgh, joined the rest of the troops, including Barney's men and other reinforcements, and encamped until Tuesday morning. On that morning we were reviewed by the President, kept under arms all morning, and then Peter's artillery, Davidson's infantry, and Stull's riflemen, still forming the advanced guard, marched to within a mile and a half of Upper Marlborough, had a skirmish with the advance of the enemy, retired in order (except the riflemen, who had fired until the enemy were so close as to oblige them to separate) and reached the encamping ground of the night before. The enemy followed, and the whole army under Winder were drawn out for battle; but the British not coming up, it was determined to march us back to the city, where we arrived very late on Tuesday night, after a most fatiguing march of upwards of 25 miles by the advance guard. The two eastern branch bridges were burnt by our own men. On Wednesday morning, we were ordered for Bladensburgh. On this side [of] the bridge, we were formed on the heights for action, saw the enemy approach, and in a few minutes the battle was commenced by the artillery form Baltimore, Berney's artillery, Pinkney's riflemen, Sterrett's regiment, and the marine corps of this city. Peter's artillery immediately opened fire—We covered them. For half an hour those troops, composing not much more than a third of the army maintained the action in a gallant style. The scene was awful. Victory was doubtful, but we did not cease to expect it until we were ordered to retreat, nobody near could tell why. It is true that Sterret's regiment had begun to give way; but it was because it had not been supported at all. The regulars did not fire a gun; few of the Americans, many of the British, were killed and wounded. The retreat was more fatal than the enemy's fire. The men were exhausted, some of them fainted, and two or three died with fatigue. All expected that we should be formed again on capitol hill, when to our astonishment the troops were ordered above Georgetown towards Montgomery court house. The city was left a prey to the invaders, who burnt the capitol, the President's house and the publick offices. The navy yard, the only legitimate object of destruction, was set fire to by our own people. Thus was the American capitol, ******************* almost unresistingly yielded to an enemy, many of whom acknowledged that if we had fought they would have been beaten.

I do not pretend to censure any one in particular; but a dread responsibility rests somewhere. I almost blush to put on the American uniform. The men, however, are not to blame.

Things are not yet restored to order here. Some of the enemy's ships and barges below appear disposed still farther to molest us. The district troops are under arms.

Cockburn destroyed the materials of the National Intelligencer. It was a pitiful act. That paper, by the assistance of the book offices, will probably be published again on Wednesday morning.

I cannot describe the distress of the female part of our inhabitants, many of whom flew into the country without a hiding place or a protector, and many remained behind, agonizing under the constant expectation of brutal insult and injury.

P.S. Several British ships have got up to Alexandria, and the town is said to have capitulated on very ignominious terms. They were at the mercy of the enemy.

Source:

This account was published in multiple newspapers, including papers in Baltimore, Maryland, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This particular transcription was taken from The United States Gazette, September 7, 1814, Page 8.

Related Battles

200

250