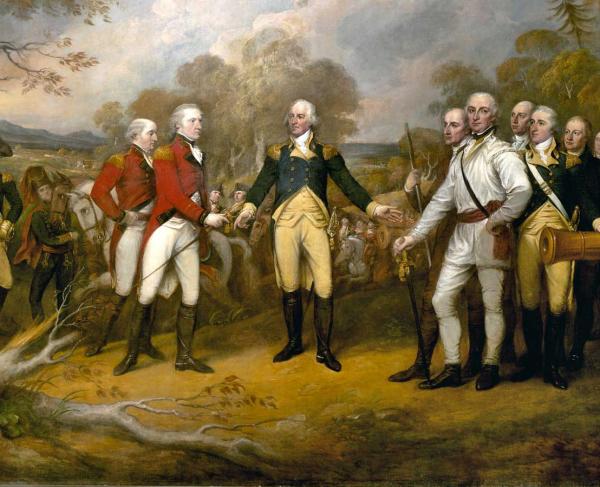

Battle of Bennington, engraving from painting by Alonzo Chappel.

Bennington

New York | Aug 16, 1777

In the summer of 1777, Gen. John Burgoyne’s army moved south from Canada as part of the overall British strategy to divide New England from the rest of the rebellious American colonies. The British commander’s army was slowed by poor roads as well as trees and other obstacles strewn along the route by the Americans. Burgoyne’s supply line was stretched thin, forcing the general to explore opportunities to replenish his forces. When Burgoyne learned of horses and supplies in Bennington, Vermont – south of his position and east of the Hudson River – the 55-year-old commander divided his army, sending German, British, Loyalist, and Native American forces toward Bennington under the leadership of Lt. Col. Friedrich Baum.

As Baum’s troops moved southeast, local militia units learned of his activity and began to prepare for action as the bulk of the American forces in the area pulled back under attack by Burgoyne’s vanguard. Baum sent couriers to Burgoyne asking for reinforcements as additional intelligence indicated a force of militiamen – he referred to them as “uncouth militia” – gathered to stop him.

American forces were led by Gen. John Stark, a hero of the Battle of Bunker Hill and a veteran of the Battle of Trenton. When Stark sent out calls for additional forces to rally to his side, a Continental Army regiment led by highly respected Col. Seth Warner was among the forces that responded. Loyalists also assembled in support of Baum. Finally, on August 16, 1777, after a day of non-stop rain, Baum’s command was attacked by over a thousand American militiamen in Walloomsac, New York, about 10 miles from Bennington.

Hoping that poor weather might delay an American advance and that reinforcements from Burgoyne would soon arrive, Baum’s troops constructed a series of breastworks on a hill. When the weather cleared on the afternoon of August 16, the Americans made their move. To inspire his men, Stark reportedly proclaimed, "There are your enemies, the Red Coats and the Tories. They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow." Unfortunately for Baum, he was duped by men entering his camp professing to be Loyalist recruits. Some of them turned out to be Stark’s militiamen, whose aim was to gather intelligence and report back to their commander.

After heavy fighting, American forces were able to breach their enemy’s defenses. Stark later claimed it was “the hottest engagement I have ever witnessed, resembling a continual clap of thunder." For some combatants, the fight was personal. It was a desperate struggle; former friends who had grown up together in Vermont or the surrounding area found themselves facing off with each other.

A century later, a romanticized tale, known as the "Glick" account, reportedly written by a German veteran of the battle, gained popularity and currency in retellings of the battle. “For a few seconds the scene which ensued defies all power of language to describe,” he recalled. “The bayonet, the butt of the rifle, the sabre, the pike were in full play as men fell, as they rarely fall in modern war, under the direct blows of their enemies.”

Within a short period of time, Patriot forces had Baum and his men surrounded. Baum himself was mortally wounded leading his Germans in dogged resistance on the knoll, where they were overrun. Many of his Native and Loyalist allies fled in the heat of the battle.

The battle continued until nightfall when darkness brought the battle to a halt. Unfortunately for Baum, his reinforcements arrived just after the battle. Burgoyne’s detachment suffered more than 200 dead and seriously wounded; more than 700 were taken prisoner or missing. American casualties were about 70.

The defeat put a major strain on Burgoyne’s army, which, in addition to the casualties suffered, never secured the provisions the British commander needed. Burgoyne's Native American allies lost confidence in him and his mission and left his army to fend for itself in the New York wilderness – deprived of its best-scouting forces. The Battle of Bennington was the precursor to the defeat of Burgoyne’s army two months later at Saratoga, turning the tide of war in favor of the Americans.

All battles of the Saratoga Campaign

Related Battles

2,350

1,450

70

907