“Stand Your Guard,” a National Guard Heritage Painting by Don Troiani depicting the Battle of Lexington and Concord.

Lexington and Concord

Massachusetts | Apr 19, 1775

In this first battle of the American Revolution, Massachusetts colonists defied British authority, outnumbered and outfought the Redcoats, and embarked on a lengthy war to earn their independence.

How It Ended

American victory. The British marched into Lexington and Concord intending to suppress the possibility of rebellion by seizing weapons from the colonists. Instead, their actions sparked the first battle of the Revolutionary War. The colonists’ intricate alarm system summoned local militia companies, enabling them to successfully counter the British threat.

In Context

Thomas Gage was appointed Royal Governor of Massachusetts in 1774 and tasked by the British Parliament with stamping out rising unrest caused by restrictive British policies. Gage inflamed tensions between the colonies and the mother country and practiced harsh enforcement of British law. He drafted the Coercive Acts, a series of laws intended to punish colonists for deeds of defiance against the King, such as the Boston Tea Party.

By April 1775, Gage was facing the threat of outright rebellion. He hoped to prevent violence by ordering the seizure of weapons and powder being stored in Concord, Massachusetts, twenty miles northwest of Boston. But he underestimated the courage and determination of the colonists. Patriot spies got wind of Gage’s plan. On the evening of April 18, Paul Revere and other riders raised the alarm that British regulars were on their way to Concord. Minute Men and militias rushed to confront them early on April 19. Though it is uncertain who actually fired the first shot that day, it reverberated throughout history. Eight years of war followed, and those who stood their ground against Gage’s troops eventually earned independence from Britain and became citizens of the democratic United States of America.

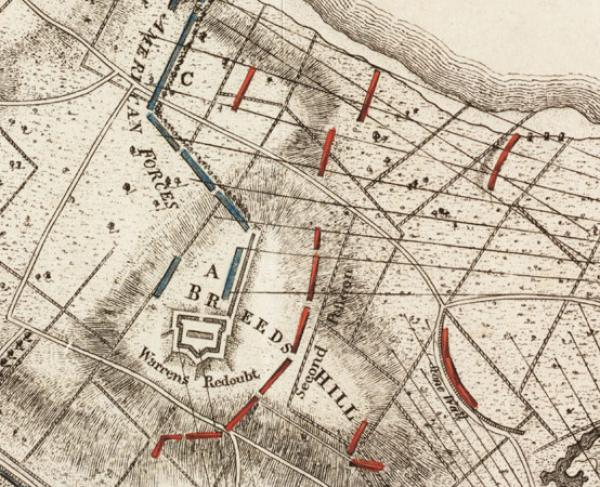

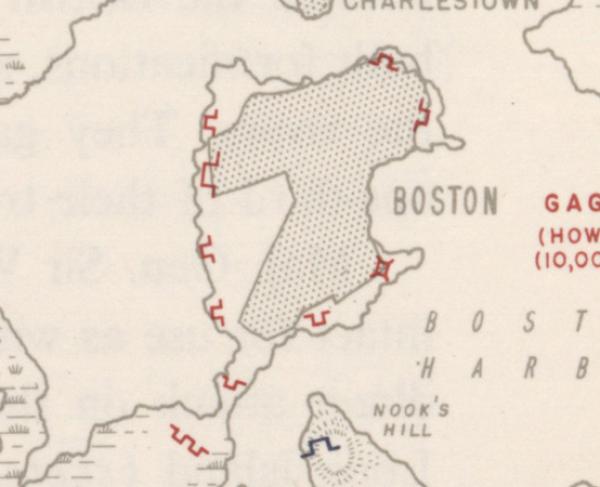

British Lt. Col. Francis Smith assembles the 700 regulars under his command to capture and destroy military stores presumably hidden by the Massachusetts militia at Concord. When the King’s troops depart Boston for Concord on the evening of April 18, anti-British intelligence quickly informs patriot leader Dr. Joseph Warren about their intentions. Warren sends for riders Paul Revere and William Dawes to spread the alarm. Revere takes the short water route from Boston across the harbor to Charlestown, while Dawes rides out across Boston Neck. Revere and Dawes depart Boston around 10:00 p.m. At the same time, two lanterns briefly flicker from the Old North Church steeple, a prearranged signal designed by Revere to alert the patriot network that the British will row across Boston harbor instead of marching out over the Neck.

On reaching the Charlestown shore, Revere mounts and begins his ride to Lexington. As he passes through the towns of Somerville, Medford, and Menotomy (now Arlington), other riders set out, guns fire, and church bells peal—all warning the countryside of the coming threat. Minute Men grab their weapons and head for town greens, followed by the rest of the militia. By the time the British cross the water, word of their imminent arrival has already reached Concord.

April 19. British troops march into the small town of Lexington at about 5:00 a.m. to find themselves faced by a militia company of more 70 men led by Capt. John Parker. When the vanguard of the British force rushes toward them across the town green, Parker immediately orders his company to disperse. At some point a shot rings out—historians still debate who fired it—and the nervous British soldiers fire a volley, killing seven and mortally wounding one of the retreating militiamen. The British column moves on toward Concord, leaving the dead, wounded, and dying in their wake.

Arriving in Concord at approximately 8:00 a.m., British commanders Francis Smith and John Pitcairn order several companies, about 220 troops in all, to secure the North Bridge across the Concord River and then continue on another mile to the Barrett Farm, where a cache of arms and powder is presumably located. A growing assembly of close to 400 militia from Concord and the surrounding towns gather on the high ground, where they see smoke rising from Concord. Mistakenly assuming the Redcoats are torching the town, the militia companies advance. The Acton Company, commanded by 30-year-old Capt. Isaac Davis, is at the head of the column. When asked if his men are prepared to confront the British troops, Davis says, “I haven’t a man afraid to go.”

As the Minute Men march down the hill, the British soldiers, intimidated by their numbers and orderly advance, retreat to the opposite shore and prepare to defend themselves. When Davis’s company comes within range, the Redcoats open fire, killing Davis and also Abner Hosmer, another Acton Minute Man. Major Buttrick of Concord shouts, “For God’s sake, fire!” and the Minute Men respond, killing three British soldiers and wounding nine others. This volley is considered “the shot heard round the world” and sends the British troops retreating back to town.

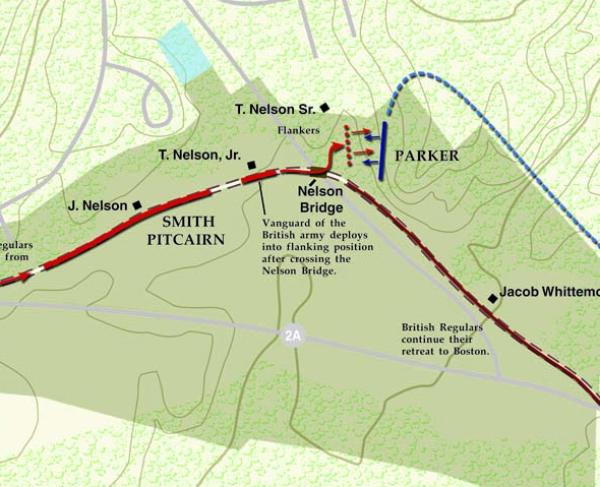

Smith and Pitcairn order a return to Boston, which devolves into a rout as the British are attacked from all sides by swarms of angry Minute Men along what is now known as Battle Road. When they reach Lexington, Parker’s men take their revenge for the violence suffered that morning, firing on the British regulars from behind cover. For the next 12 miles, the British are continually ambushed by Minute Men shooting from behind trees, rock walls, and buildings. British reinforcements reach Smith and Pitcairn’s men on the eastern outskirts of Lexington, but the Minute Men pursue them as they retreat back to Boston.

93

300

The British conduct a running fight until they can reach the cover of British guns on ships anchored in the waterways surrounding Boston. The Patriots chase them but, having no clear orders, ultimately let them escape.

In the wake of Lexington and Concord, Governor Gage finds Boston faced by a huge militia of men who have arrived from throughout New England to fight for liberty. Numbering 20,000, this resolute force will become part of the Continental Army.

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, participants and witnesses on both sides gave depositions testifying to the events of April 19, 1775. Eager to get the colonists’ version of the battle to London before Governor Gage’s testimony could arrive at Parliament, the Provincial Congress rushed to print 100 copies of their own narrative and sent them by schooner to England. The American story hit the London newspapers before Gage’s account arrived. It began:

ON the nineteenth day of April one thousand, seven hundred and seventy five, a day to be remembered by all Americans of the present generation, and which ought and doubtless will be handed down to ages yet unborn, in which the troops of Britain, unprovoked, shed the blood of sundry of the loyal American subjects of the British King in the field of Lexington. Early in the morning of said day, a detachment of the forces under the command of General Gage, stationed at Boston, attacked a small party of the inhabitants of Lexington and some other towns adjacent….

Governor Gage submitted his own “Circumstantial Account of an Attack” at Lexington and Concord, which was drawn from several different testimonies and intended to win support for the regulars’ actions:

When they arrived at the End of the Village, they observed about 200 armed Men, drawn up on a Green, and when the Troops came within a Hundred Yards of them, they began to file off towards some Stone Walls, on their right Flank : The Light Infantry observing this, ran after them ; the Major instantly called to the Soldiers not to fire, but to surround and disarm them ; some of them who had jumped over a Wall, then fired four or five Shot at the Troops, wounded a Man of the 10th Regiment, and the Major's Horse in two Places, and at the same Time several Shots were fired from a Meeting-House on the left: Upon this, without any Order or Regularity, the Light Infantry began a scattered Fire, and killed several of the Country People; but were silenced as soon as the Authority of their Officers could make them.

Some of those who gave testimony in 1775 later changed their minds about what happened, and the biases of both sides make conclusions difficult. Despite these public relations campaigns to set the story straight, we still don’t know the truth.

When the alarm about the regulars’ advance reached families along the Battle Road, many women were left behind while their husbands set off to join their militias. As the British searched homes for contraband, some of them deftly shielded secret stores of arms from the Redcoats, risking personal harm. They slyly misled the troops as to the whereabouts of valuables or quickly buried contraband before the regulars showed up at their doors.

Mary Moulton of Concord was particularly heroic. When Pitcairn’s troops set a fire that threatened to spread, Moulton implored the soldiers to extinguish the flames and saved her town from destruction. Moulton later detailed her deed in an application for a pension:

Your petitioner, being left to the mercy of six or seven hundred armed men, and no person near but an old man of eighty-five years, and myself seventy –one years old, and both very infirm…. cultivated so much favor as to talk a little with them. When all on a sudden they had set fire to the great gun carriages just by the house, and while they were in flames your petitioner saw smoke arise out of the Town House higher than the ridge of the house. Then your petitioner did put her life, as it were, in her hand, and ventured to beg of the officers to send some of their men to put out the fire; but they took no notice, only sneered…. your petitioner (not knowing but she might provoke them by her insufficient pleading) yet ventured to put as much strength to her arguments as an unfortunate widow could think of; …At last, by one pail of water after another, they sent and did extinguish the fire.

There are were doubtless many other colonial women—both white and black, free and enslaved—who took on unheralded roles that day as hundreds of regulars marched into their towns. That we don’t know their names or more about them is largely due to their subservient status in a society that denied them autonomy, education, and recognition.

Lexington and Concord: Featured Resources

All battles of the Boston Campaign

Related Battles

3,960

1,500

93

300