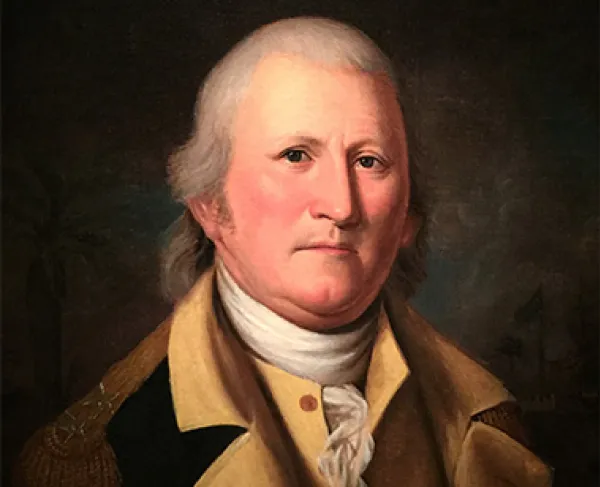

"Sir Peter Parker's Attack Against Fort Moultrie," oil on canvas. Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.

Sullivan's Island

Fort Sullivan, Fort Moultrie

Charleston County, SC | Jun 28, 1776

In the summer of 1776, British General Henry Clinton attacked Fort Sullivan just outside the city of Charleston, South Carolina, defended by William Moultrie. In the resulting action, Moultrie successfully defended the fort and saved the city.

How It Ended

Patriot Victory. After his bombardment failed to force the fort's garrison into submission, Clinton realized that his attempt to capture the city of Charleston was over and decided to pull back his fleet into the Atlantic Ocean.

In Context

As the British evacuated Boston in March 1776 and regrouped along the coast, plans were made on what to do to curb the American rebellion. One such strategy was the possibility of sailing south, establishing a foothold in the southern colonies, and rallying loyalist support to retake the provincial governments that were being ousted by patriot forces. Royal governors put forth such claims of widespread loyalists eager to join the fight in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia. The British commander-in-chief, Sir William Howe, sent his second-in-command, Sir Henry Clinton, with a detachment of troops to secure these claims and aid in the unfolding campaign of 1776. To help Clinton, Lord Cornwallis was called upon with his fleet to help serve the area and find the best spot to land the British army. Cornwallis staff soon selected Charleston, South Carolina, since they believed its defenses outside the city were no match for the British Navy.

Standing in the way of the British was the unfinished fort on Sullivan's Island and its commander, Colonel William Moultrie. Before the battle, Americans observed the importance of the island's location since any ship had to pass through its southern tip to enter Charleston. By February 1776, engineers began constructing a fort to defend the city. Using palmetto trees, the Americans built walls by placing two cut logs sixteen feet apart and filling the space with clay and sand. Unknown to the British was the unique durability of palmetto wood. Unlike other types, palmetto fiber absorbed impact like sponges, whereas other treed woods would splinter and shatter. The five-hundred-foot square fort with high, sixteen-foot-wide sides filled with sand and planked gun platforms, holding thirty-one assorted cannons, would be Charleston's first line of defense.

Most British fleets arrived outside the harbor on June 1, 1776. Parker instructed, “his frigates, and if possible, the Bristol may go over Charles Town Bar to make a diversion.” In contrast, Clinton’s infantry made the main assault against the half-finished palmetto and sand fort on Sullivan’s Island. With the British fleet crossing into Five Fathom Hole on June 8, Clinton issued a proclamation to deliver to the rebels demanding them to surrender the town. Three North Carolina Regiments of 1,400 men arrived in town the same day under the command of Brigadier General John Armstrong. The British had trouble getting their frigates over the shallow Charles Town bar because they were too heavy. When Clinton received no word on his surrender offer, he decided to begin the assault against Sullivan’s Island. Clinton did not want to land on Sullivan’s Island under heavy fire, so he put his ground forces ashore at 10:00 am “through a heavy surf” on northern Long Island on June 9, across from Breach Inlet. The day the British landed, Major General Charles Lee arrived in town.

Tensions soon flared between Moultrie and Lee, with the latter believing that Fort Sullivan needed to be abandoned and its garrison fall back towards the city. However, after exchanging several letters and discussions, Moultrie could stay at Fort Sullivan.

6,400

2,500

From his perch on Long Island north of Breach Inlet, Clinton surveyed Fort Sullivan. With faulty intelligence stating the waters to be shallow, on the morning of June 28, Clinton personally led his infantry into the waters of Breach Inlet only to discover a ripping current and an inlet far too deep to wade across. He next tried to cross using flatboats, but the sniper fire brought on by Thomson's detachment of 800 troops drove the British back. Moultrie, who was visiting Thomson's position, saw the British maneuvers and immediately raced to the fort on horseback to prepare for the unfolding battle. However, isolated, Clinton had to abandon the original plan to attack Fort Sullivan from a combined assault from the sea and by land, miles apart.

At 10:00 am, the HMS Thunder, a warship with mounted mortars, anchored a mile from the fort and began to lob its shells. Parker's British vessels were brought up against the fort "in the following order: the Active against the three guns on the face of the east bastion, Bristol against five guns in the curtain and two on the flank of the east bastion, Experiment against the four remaining guns in the curtain and the two on the flank of the west bastion. The Thunder Bomb, covered by the Friendship, brought the salient angle of the east bastion to bear." They dropped anchor and opened broadside fire on the fort, with over 7,000 rounds of cannon and mortar fire striking about the fort.

Due to limited supplies of powder, Moultrie's men slowly and steadily replied, making each shot count. Despite being only a few hundred yards off the coastline, the clouds of gun smoke from the British ships were so thick the Americans temporarily lost sight of them. Only twelve of Moultrie's cannons could be brought to bear effectively on the British fleet's locations. In return, the British were not doing any real damage to the fort because the spongy palmetto logs absorbed the cannon balls. Many of the ships were either anchored too far from or in the wrong position for their cannon to have the desired effect on the fort. The HMS Thunder's mortars were doing so little damage that the British crewmen began overpacking her cannon with powder to give her shot more velocity. The result was the heavy mortars, held down by special wood planks, buckled the planks and began destroying the ship's deck. She would have to leave the fight entirely by mid-afternoon.

For every fifty British fleet shots fired, Fort Sullivan fired but one, most of which proved deadly accurate on their targets. A British shot at one point cut the fort's flagstaff. Sergeant William Jasper jumped up on the ramparts, over the walls, to retrieve the colors, ignoring the rain of the shot and shell. Jasper then climbed back up, tied the flag to an artillery sponge staff, and erected it on the fort to be seen.

Moultrie wrote that Lee visited the fort during battle and "pointed two or three guns himself; then said to me 'Colonel, I see you are doing very well here, you have no occasion for me, I will go up to town again,' and then he left us." The Sphinx, Syren, and Actaeon sought to take advantage of the tremendous British broadsides and sailed past the fort, planning to take up a position from where they could attack the fort on its weak side. Unfortunately, the three ships ran aground over the sandbar known as the middle ground. By mid-afternoon, the Sphinx and the Syren were free, but the Actaeon remained aground.

37

220

By nightfall, the battle finally began to subside. The Bristol was barely keeping herself afloat, and as darkness set in, Parker withdrew his forces around 9:30 pm, setting sail for the Atlantic. The Bristol alone had fired 1,840 cannon shots to little effect.

Moultrie remained at the Fort, assuming the British might plan a second offensive. Instead, at 2:00 am on the morning of the 29th, the British set the grounded Actaeon on fire and abandoned it. Meanwhile, Charleston folks did not know if the Fort had been victorious or if it had been captured. Moultrie sent a boat to inform them of the good news, and loud cheers reverberated through the streets. The defense had been a major victory for the Americans in Charleston. General Lee wrote, "The behavior of the Garrison, both men, and officers, with Colonel Moultrie at their head, I confess astonished me." Six days later, the Declaration of Independence was signed in Philadelphia. Afterward, the South Carolina General Assembly renamed Fort Moultrie in honor of the commander of Fort Sullivan. The Fort's defenses were tired again in the spring of 1780 when Lord Cornwallis tried its defenses again and captured the Fort and then the city of Charleston.

During the construction of Fort Sullivan in February of 1776, Patriot engineers used Palmetto trees and sand to help bolster the island's defenses. Unlike regular wooden fortifications, Palmetto trees and sand were extremely durable and could absorb the blow from artillery shells. During the Battle of Fort Sullivan, the British Navy bombarded the fort for several hours, resulting in over 1,000 artillery shells firing into the Patriot lines. Surprisingly to the British Navy, most of the shells did little damage to the fort. As a result, William Moultrie's garrison was able to fire back with a devastating effect on the British fleet, eventually forcing them to withdraw.

Since the city's founding in 1670, Charleston quickly grew as a seaport, and because of this commerce, its influence grew over the region. In 1776, the British army was forced to evacuate from the city of Boston, having been besieged there since 1775. British General William Howe, commander of the British forces in North America, decided to move his army towards the south, where royal governors from the area told him that many of their subjects were still loyal to the King. After British engineers surveyed Charleston, by then one of the largest ports in North America, they decided that this southern city was the best place to attack, and Howe sent Henry Clinton to attack the city. However, in the summer of 1776, Clinton's forces were stopped at the Battle of Fort Sullivan. It would not be until 1780, when the British decided to attack the city for a second time, that they were successful.

Related Battles

6,400

2,500

37

220