The Liberty Trail

An unforgettable journey through place and time

America’s independence was secured in South Carolina across its swamps, fields, woods and mountains. These events of 1779-1782 directly led to victory in the Revolutionary War. We call this history The Liberty Trail.

The Liberty Trail

America’s independence was secured in South Carolina across its swamps, fields, woods and mountains. These events of 1779-1782 directly led to victory in the Revolutionary War. We call this history The Liberty Trail.

The Liberty Trail—developed through a partnership between the American Battlefield Trust and the South Carolina Battleground Trust—connects battlefields across South Carolina and tells the captivating and inspiring stories of this transformative chapter of American history.

Connecting Revolutionary History

The vision for The Liberty Trail is ambitious, with the goals of permanently protecting more than 2,500 acres of battlefield land and ultimately linking nearly 80 sites.

The Liberty Trail tour guide app connects 30 National Parks, SC State Parks, and local sites with a series of new battlefield parks being developed through The Liberty Trail partnership. Additional sites and features will continue to be added.

Combining the preservation of these hallowed battlegrounds with unique on-site interpretation and cutting-edge digital features, The Liberty Trail will connect visitors to the extraordinary events that came to pass nearly 250 years ago and honor the patriots that decided the Revolution’s outcomes in South Carolina.

Explore The Liberty Trail

The Patriots’ palmetto-log fort on Sullivan’s Island resisted cannon fire from Royal warships and saved the port of Charleston from invasion. This American victory over the powerful British Navy shocked the world.

William “Danger” Thomson’s forces defended the east end of Sullivan’s Island, preventing British troops from crossing over the treacherous Breach Inlet to reach the Patriots’ vulnerable defenses and take Charleston.

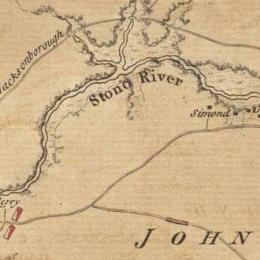

British General Augustine Prevost aborted a raid on Charleston and retreated, leaving troops in fortifications at Stono Ferry. Patriot General Benjamin Lincoln launched a failed and bloody assault on those defenses.

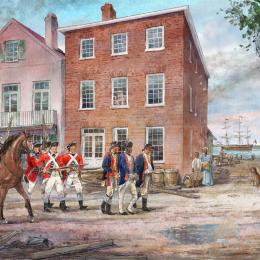

During their Southern Campaign, the British laid siege to the vital port of Charleston. After weeks of fighting, the Patriots surrendered. The victors occupied the city and established a network of rural outposts across the state.

British troops boldly attacked Continental troops and partisan militia at this vital outpost between the backcountry and the coast, resulting in the capture of a critical Patriot escape route during the Siege of Charleston.

Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion defeated Abraham Buford’s Patriot militia here in a bloodbath known afterward as “Buford’s Massacre.” The engagement inspired the Patriots’ defiant cry, “Remember Waxhaws!”

Located on the grounds of Historic Brattonsville, this was the site of the Patriot victory over the tyrannical Loyalist commander Christian Huck. His demise in the skirmish boosted the morale of the partisans.

This battleground was the site of three British camps, which were attacked by ardent Patriot troops in a fight primarily between Americans—Patriots supporting independence—and Loyalists favoring British rule.

A crushing defeat for the Patriots, this battle sapped American morale and boosted British confidence in their plan to control the Southern colonies. Horatio Gates’s errors on the field cost him his command.

After seizing Charleston, the British occupied Camden and made this their primary military post in the South Carolina interior. Today, the 107-acre site features reconstructions of colonial buildings and redoubts.

At this isolated British outpost, the Patriots used an ingenious ruse to lure the enemy into an ambush. Their victory proved that “shoot and scoot” tactics could effectively defeat a numerically superior army.

At Thomas Sumter’s abandoned plantation, Patriot Francis Marion initiated a surprise nighttime attack to release 150 Continentals held prisoner by the British after the Battle of Camden. He liberated them all.

The unexpected triumph of frontier militiamen here infused the Patriots with confidence and humiliated the King’s army. This battle was a turning point in the war.

Francis Marion’s midnight raid on a British camp of Loyalist recruits sent the panicked soldiers fleeing into the swamp. Some of them later joined up with Marion, inspiring the clever nickname “Turncoat Swamp.”

Tarleton’s pursuit of Patriot Francis Marion led him on a wild chase that ended unsuccessfully at Ox Swamp. His frustration with the “damned old fox” inspired Marion’s illustrious nickname, “the Swamp Fox.”

Patriot Thomas Sumter made a bold stand against Banastre Tarleton’s forces on these grounds and won. The Americans used the hilly wooded terrain to their advantage in a fight that cost many British lives.

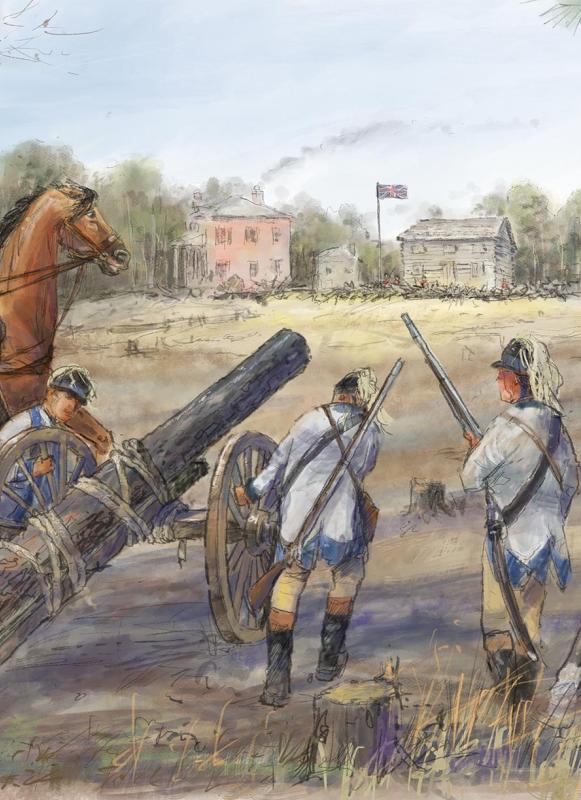

Patriot Lieutenant Colonel William Washington had no artillery to capture Henry Rugeley’s strong Loyalist fort, so he created a fake cannon from a pine log. The trick worked and Rugeley surrendered the post and his men.

At this site, British commander Robert McLeroth accused Francis Marion of violating the rules of war and proposed settling their differences in a mass duel. The aborted duel was simply a delaying tactic and allowed the British to escape.

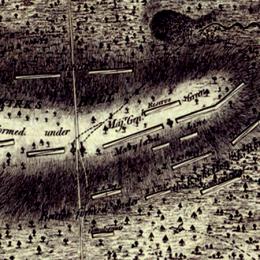

Skilled leadership by Patriot commander Daniel Morgan at Cowpens led to the defeat of British officer Banastre Tarleton’s elite forces and helped weaken the Crown’s attempts to control the southern colonies.

Intent on breaking the British Army’s supply chain, Francis Marion’s partisans conducted a surprise raid on a British depot near Wadboo Bridge and took 33 prisoners. They plundered then destroyed the site.

Francis Marion ambushed the British on the Santee River Road and the two forces faced off at this swamp. Attacks like this by Marion kept the British on edge as they struggled to keep hold of South Carolina.

After an eight-day siege here by Patriot forces, this strategic British outpost fell to the Patriots, who used an ingenious structure called a Maham Tower to fire down into the fort and trap the enemy.

Lord Rawdon led a force of 900 to attack Nathanael Greene’s army of about 1,550 at this site outside colonial Camden. When the Patriot line faltered, the British charged up Hobkirk Hill, prompting Greene to retreat.

At this major British outpost, the Patriots laid siege to the heart of the Loyalist defenses, the Star Fort. It still stands and is one of the best-preserved original Revolutionary War earthworks in the nation.

The British commander of this outpost torched his goods and ammunition inside the large church nave to prevent their capture by the Patriots. He and his men then fled toward Charleston, abandoning the site for good.

The last major battle to take place in the South, it was also the bloodiest. Afterwards, Alexander Stewart’s British forces withdrew to the safety of the Charleston defenses.

A critical part of Charleston’s defenses, Dorchester changed hands many times, from Patriot to British and back again. The fort is one of the best examples of “tabby” (oyster-shell) construction in the United States.

This site preserves one of only two Revolutionary War-era forts in South Carolina to survive intact. Patriot militia made a daring raid on this vital enemy outpost, which was later abandoned by the British.

In his last field battle of the war, Francis Marion hid his men behind the dense cedars lining the avenue to Wadboo Plantation and lured the British into an ambush. The Patriots ran out of powder and withdrew.

Now a monastery for Cistercian (Trappist) monks, this was once the plantation of Henry Laurens, a merchant, slave trader, statesman, President of the Continental Congress, and the father of Revolutionary War soldier John Laurens.

A Brief History

The large number of Revolutionary War battle sites on The Liberty Trail is evidence of how important the Southern colonies were to the British war effort. By the mid-1700s, Charleston was the richest city in America. A flourishing export trade in rice and indigo, harvested by enslaved workers on nearby plantations, made its harbor a vital and bustling port. Its streets were filled with the elegant homes of wealthy planters and merchants. In the spring of 1776, over a year after after the first guns were heard at Lexington and Concord, the British attempted to wrest this jewel on the Atlantic coast from the Patriots in the Battle of Fort Sullivan. After their failure, the focus of the fight shifted back to the northern states. By 1778, however, with the war in the North at a stalemate, British command believed that it was time to launch a Southern Campaign.

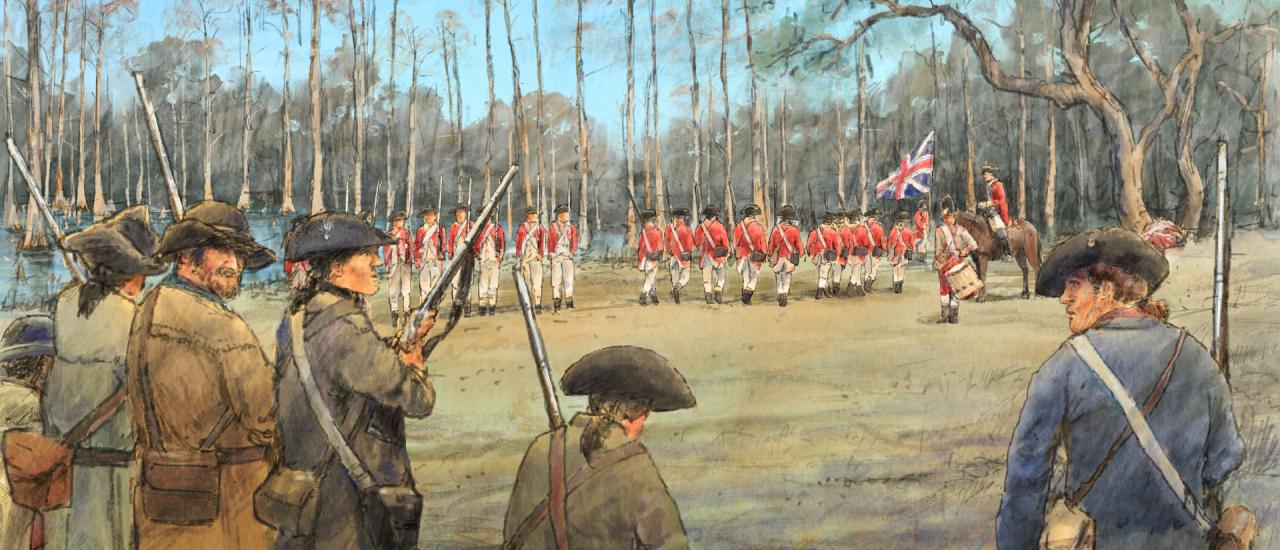

The British were convinced that loyal southern citizens would help them subdue rebellion and restore the authority of the Crown. The successful capture of Savannah, Georgia, on December 29, 1778, inaugurated their strategy. A failed attempt by Patriot Major General Benjamin Lincoln to retake the city in 1779 bolstered Britain’s ambition to subdue the Southern colonies. By February 1780, British Commander-in-Chief for North America, Sir Henry Clinton, landed approximately 12,500 troops outside Charleston and laid siege to the city. With his force of just 5,000, Benjamin Lincoln could not resist the attack and surrendered the Patriot defenses to the enemy on May 12. The brutal engagement left the Southern Continental Army in tatters, and the British quickly set up outposts in the rural interior so they could easily move supplies and Loyalist recruits from the coast to the backcountry.

British efforts to suppress local rebellion after the occupation of Charleston took an unexpected turn and fueled discord between Loyalists and Patriots, pitting neighbor against neighbor. The source of the divisiveness was a British proclamation of June 3, 1780, which changed the terms of parole granted to Patriot militia after the Siege of Charleston. The condition of neutrality they agreed to suddenly no longer applied, and those who had gone home on parole were now forced to fight for the Crown or become an enemy of the state. If they refused to sign an oath of loyalty, they could be imprisoned or hanged. Their families could be captured or killed, and their homes and crops burned to the ground. Rather than win the British the allegiance they sought, the proclamation and violent aftermath stoked distrust and a desire for independence. Many of the paroled rushed to reenlist in the Patriot cause, leaving their farms and plantations to join partisan brigades.

As the Patriots in the southern colonies hustled to recruit, muster and train militia to counter the British occupation, well-drilled Royal and Loyalist troops overwhelmed them in key battles. At Waxhaws in late May 1780, British Legion commander Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton devastated the Patriot force under Colonel Abraham Buford in an encounter later known as “Buford’s Massacre.” At Camden, on August 16, Commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army, Horatio Gates, was run off the battlefield by Charles Lord Cornwallis’s elite troops. Slowly, however, these partisan defeats incited defiance and strengthened Patriot resistance. Patriot victories at Huck’s Defeat, Hanging Rock, and Rocky Mount that summer buoyed morale. Partisan leaders—like Thomas Sumter, Francis Marion, and Andrew Pickens—fanned the spirit of revolt in remote areas and fought a relentless and savage guerilla war against their Loyalist neighbors. The intensity of the violence in the backcountry stunned Carolina outsiders such as Patriot Major General Nathanael Greene, who later said, “The whole country is in danger of being laid waste by the Whigs and Torrys, who pursue each other with as much relentless fury as beasts of prey.” That fury ultimately turned the tide of the war.

On August 18, 1780, about 200 mounted Patriots arrived near the Loyalist outpost of Musgrove Mill and ensnared a greater number of British Provincials and Loyalist militia in a deadly trap. With the help of the Overmountain Men—frontiersmen from west of the Appalachians—the Patriots had stunning victories over the British at King’s Mountain in October 1780 and Cowpens in January 1781. The arrival of Nathanael Greene in the winter of 1780, who replaced Gates as commander of the Continental Army in the South, further bolstered the American cause. Greene played a game of cat and mouse with Cornwallis, luring him into North Carolina in a maneuver that became known as “the Race to the Dan,” a critical river barrier that would cut the British off from their supply lines. The race ended in the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781, where Cornwallis held the field but suffered heavy casualties. Unable to trap Greene, Cornwallis marched his men to Wilmington, and, later, into Virginia.

In April 1781, Fort Watson became the first British outpost to fall to the Patriots after the Siege of Charleston, and it paved the way for future partisan victories at Fort Motte and Fort Granby. The surrender of Fort Watson and the Battle of Hobkirk Hill also helped prompt British General Lord Rawdon to evacuate the important operational British base at Camden in May. Despite the British victory at Ninety Six in June, rural posts were gradually abandoned, and after the Patriots inflicted heavy losses on the enemy at Eutaw Springs in September, the British retreated toward Charleston. Cornwallis surrendered his army to George Washington at Yorktown in October 1781, but skirmishes persisted in the South for another year. Royal troops evacuated Savannah in July 1782. Finally, on December 14, 1782, the British boarded their ships in Charleston Harbor and sailed away from the southern coast, ending seven years of war in the South.

Saving Land

The cornerstone of The Liberty Trail is the preservation of hallowed battlegrounds. Through this initiative, thousands of acres of land will be permanently protected. Today, most of these sites are blank slates — quiet fields and forests waiting to tell their stories.

To date, we have preserved nearly 700-acres at eight battlefields in South Carolina: Camden, Eutaw Springs, Fort Fair Lawn and Colleton Castle, Hanging Rock, Parker’s Ferry, Port Royal Island, Stono Ferry, and Waxhaws.

This devastating American defeat ultimately resulted in changes that helped turn the tide of the War toward victory for the cause of Independence.

The site of an extant Revolutionary War fort built by the British in 1780, Patriot forces launched an attack here in 1781.

The British outpost at Hanging Rock was attacked by Thomas Sumter and Patriot forces in August 1780, contributing to the broader efforts to drive the British out of South Carolina.

After the fall of Charleston, the brutal attack by Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion on Virginia Continentals at the Waxhaws rallied support for the Patriot cause.

Our Valued Partners

South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust

The South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust is a 501(c)(3) not-for profit corporation established in 1991 and dedicated to the preservation of South Carolina’s historic battlegrounds and military sites. Working with property owners, developers, and local/state agencies, the South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust has successfully preserved historic properties throughout South Carolina. The organization preserves South Carolina's military heritage employing a variety of tools from conservation easements and land acquisitions to high-tech ground-based laser scanning surveys and public interpretation with the goal of ensuring the state’s military heritage sites are not forgotten and there to study, discuss and reflect upon for future generations.

The South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust has partnered with the American Battlefield Trust to lead this historic effort to protect The Liberty Trail’s battlefields and bring them to life. Learn more about them at https://www.scbattlegroundtrust.org.

Lead Sponsor

The Liberty Trail would not be possible without the generosity of Lorna Hainesworth, Ambassador and National Traveler. Ms. Hainesworth has visited each and every stop on The Liberty Trail, and many places beyond. We are beyond grateful for her generosity.

Additional Thanks

The Liberty Trail would also not be possible without numerous valued partners at the federal, state, and local levels.

- National Park Service

- South Carolina Department of Archives and History

- South Carolina Department of Parks, Recreation & Tourism

- South Carolina State Parks

- South Carolina Association of Tourism Regions

- South Carolina American Revolution Sestercentennial Commission

- Berkeley County Soil & Water Conservation District

- Charleston County Greenbelt Program

- Kershaw County

- Lancaster County

- Town of Heath Springs

- Town of Sullivan’s Island

- Department of the Navy

- Audubon South Carolina

- Beaufort County Open Land Trust

- Charleston County Public Library

- Charleston Museum

- Cherokee Historical and Preservation Society

- Clemson/College of Charleston Historic Preservation Program

- Colleton County Historical Society

- Historic Camden Foundation

- Katawba Valley Land Trust

- Lord Berkeley Conservation Trust

- Morris Center in Ridgeland

- Palmetto Conservation Foundation

- Preservation South Carolina

- Santee Cooper

- Spartanburg County Historical Association

- Sumter Guards

- Washington Light Infantry