(Washington, D.C.) — Dramatic scenes of the final fighting between Robert E. Lee’s and Ulysses S. Grant’s men are being preserved for posterity by the American Battlefield Trust.

Working over several years, the nation’s top historic land-preservation nonprofit has purchased six parcels that tell gripping stories of the actions by Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Grant’s Army of the Potomac at Appomattox Court House.

The tracts include part of the ground where the battle’s last fighting near the courthouse occurred, incurring casualties even though truce flags had appeared. The six properties — totaling 276 acres — are adjacent to Appomattox Court House National Historical Park and to other land the Trust has saved in prior preservation efforts, starting in 2000.

“Trust members and our government partners have achieved remarkable success at Appomattox, preserving the land where the Civil War effectively ended and a new chapter in our nation’s history began,” Trust President James Lighthizer said. “It is only fitting that we celebrate now. Our victories fortify us for the effort that remains.”

The total value of the six real-estate transactions is $1.81 million. Trust fundraising for them, over two annual campaigns, began in 2015.

The land was purchased with a combination of private-sector donations from American Battlefield Trust members and state and federal grants from the Virginia Battlefield Preservation Fund and the National Park Service’s American Battlefield Protection Program.

The Trust recently received a Virginia Battlefield Preservation Fund grant for the latest parcel, which it acquired this summer. A conservation easement on those eight acres is pending with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

As a condition of the easements held by the Department of Historic Resources on the six parcels, the Trust will raze modern houses on some of the six tracts to restore the land to something closer to its wartime appearance.

All told since 2000, the Trust has preserved 557 acres on the Appomattox Court House and Appomattox Station battlefields. After Lee’s army surrendered, Union Brig. Gen. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain called the community “that obscure little Virginia village now blazoned for immortal fame.”

Fighting around the rail station on April 8, 1865, gave the Federals control of the strategic ground necessary to force Lee’s surrender, which followed on April 9. Maj. Gen. George A. Custer’s Union cavalry division captured 25 cannons near Appomattox Station, which lies west of the courthouse town, and burned three wagons loaded with provisions badly needed by Lee’s army.

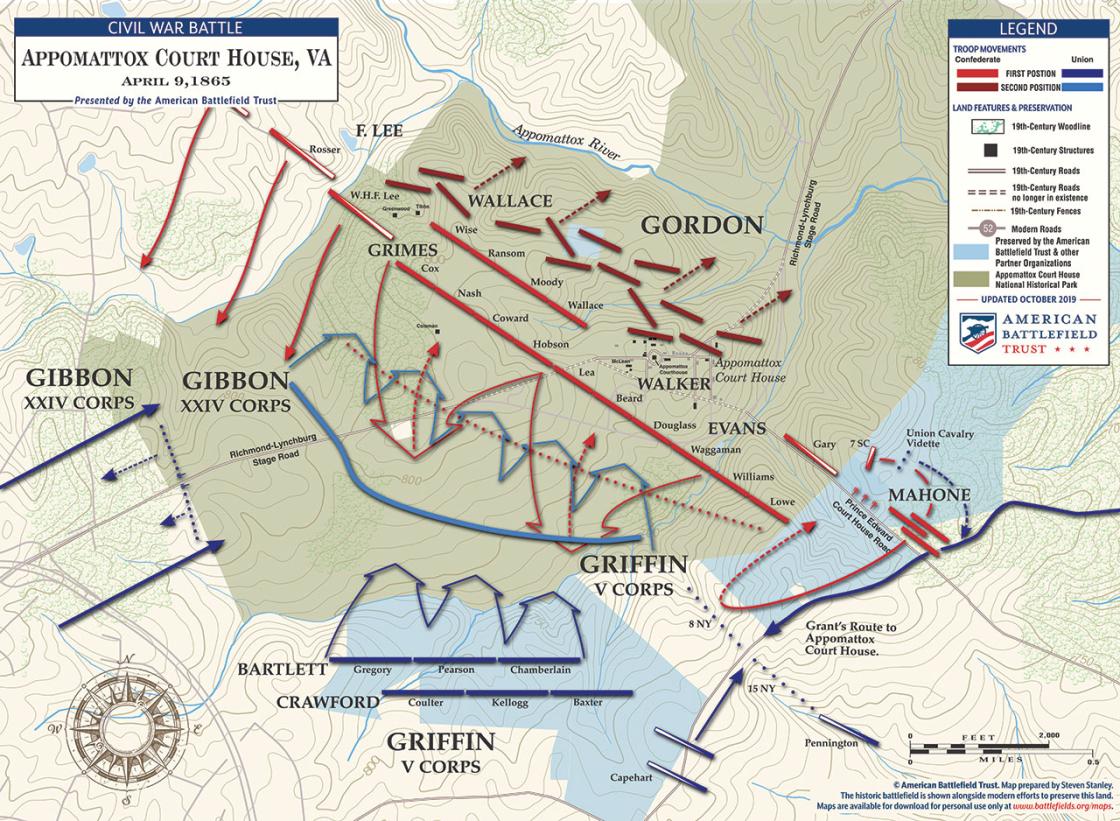

On the morning of April 9, Confederate General John B. Gordon’s 2nd Corps advanced and fought in a failed bid to open the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road as an escape route for Lee’s army. The back-and-forth fighting across the now-preserved property was some of the battle’s fiercest.

Also that morning, in the area of several of the newly preserved properties, Confederate soldier Robert Simms carried a truce flag into Custer’s line. Battlefield artist Alfred Waud sketched the scene. When Union Gens. Wesley Merritt and Philip Sheridan rode by, Custer’s several thousand soldiers gave them “three rousing cheers.” This ground, along the LeGrand Road, witnessed the battle’s last combat.

On an adjoining 201-acre tract preserved by the Trust, 12 artillery pieces and their support troops held the Confederate left flank as three Union brigades advanced, as word reached soldiers that hostilities were suspended. Sgt. Benjamin Weary of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry impetuously rode to the front of the 1st Confederate Engineers Regiment and demanded its surrender. Met with jeers, Weary snatched the regiment’s colors and started riding off, but was riddled with bullets. Buried nearby, he was later reinterred in Poplar Grove Cemetery near Petersburg.

On a different, 59-acre tract, the early morning of April 9 saw Confederates push back Union general Thomas Devin’s 1st Cavalry Division, until it was reinforced. “We had nothing to oppose Lee but cavalry and nobly did they do their work,” a 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry soldier wrote. “… They tried hard to break our line and poured in shot and shell with their musketry until the air seemed full of it.” Before a Union artillery and infantry counterattack toward the courthouse village — “a grand charge upon the enemy” with fixed bayonets — could take place, a truce flag halted the fight.

Later that day, meeting at the McLean House in the village, Lee and Grant agreed on the terms of surrender and parole for the Army of Northern Virginia. Their peaceful cessation of hostilities at Appomattox served as the model for further Confederate surrenders in the coming weeks.

The American Battlefield Trust is dedicated to preserving America’s hallowed battlegrounds and educating the public about what happened there and why it matters today. The nonprofit, nonpartisan organization has protected more than 50,000 acres associated with the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Civil War. Learn more at battlefields.org.