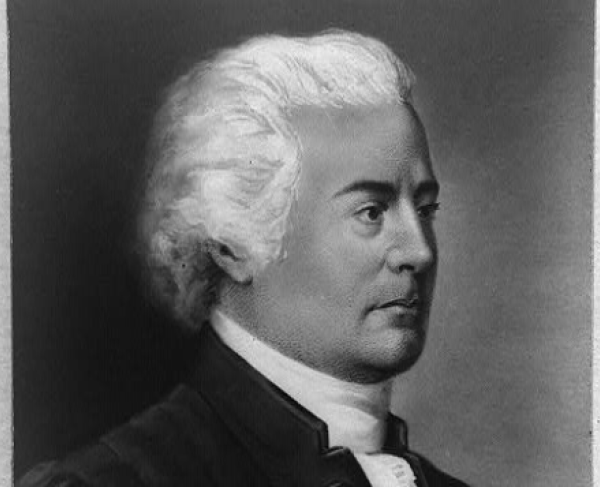

John Rutledge

John Rutledge dedicated his life to leading and serving his fellow South Carolinians. He occupied significant positions in the executive, legislative and judicial branches of South Carolina’s government.

Rutledge was born on September 17, 1739, in Charleston, South Carolina, to parents Dr. John Rutledge and Sarah Hext. Dr. Rutledge had emigrated from Ireland to South Carolina in 1735, following his brother to the colony. In addition to being a physician, Dr. Rutledge likely also served as an Anglican Minister. John was the oldest of seven children. His father died when John was eleven.

Prior to his death, Dr. Rutledge had prioritized his children’s education. By age twenty-two, John Rutledge went to London to study Law at one of the four Inns of Court, Middle Temple, and had been accepted to the English Bar. Shortly thereafter, Rutledge returned to Charleston and was admitted to the South Carolina Bar. Rutledge took on two different cases of clients accused of seditious libel. This criminal offense involved publishing or speaking poorly of the government, which during colonial rule was the British Government. He quickly became regarded as a defender of freedom of the press.

Rutledge’s legal arguments earned him a reputation as a gifted speaker and man of the law. In 1761, Christ Church Parish elected him as a representative to South Carolina’s Commons House of Assembly. To be eligible, Rutledge “had to own at least five hundred acres” and twenty enslaved people. Rutledge occupied this seat until 1775 and helped to create and implement laws, establish courts and oversee government expenditures.

As Rutledge participated in regional, colonial government, Britain—deep in national debt following the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War—implemented a series of taxes on the North American colonies to counter expenses incurred. This angered the colonists, and many believed it was unconstitutional to be taxed without representation. A congress of delegates gathered in New York in 1765 to discuss the taxes, particularly the Stamp Act, which charged a tax on many paper goods; Rutledge was one of the delegates in attendance. The outcome of the Congress was a Declaration of Rights and Grievances as well as a petition requesting the Stamp Act’s repeal sent to King George III and Parliament. The Act was repealed in 1766, nevertheless tensions between the colonists and Britain continued to rise.

Rutledge once again represented South Carolina when he attended the First (1774) and Second (1775) Continental Congresses. As a delegate at the First Congress, he wished to pursue a moderate path. Rutledge hoped the colonies would gain certain rights while continuing their relationship with Great Britain. However, following the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the Second Congress’ focus slowly changed to one of preparing for war, declaring independence and establishing a new nation.

Rutledge favored basing new governments on constitutions; he helped draft the State Constitution of South Carolina in 1776. He became President (Governor) of South Carolina, leading the state during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He set about coordinating the new government and prepared for an imminent British invasion by raising a militia. He briefly resigned as Governor in 1778, opposing changes made to the state’s constitution, but was reelected in 1779.

Three years after their first attempt to capture Charleston, the British Army returned in Spring 1780. In a printed proclamation, Rutledge wrote to South Carolinians

Whereas the Enemy have invaded this State, and now occupy John’s and James Island, and the reduction of this Town is undoubtedly their Object: And whereas it behoves the Freemen of the County bravely to resist their Efforts, which if happily defeated, (as by the Blessing of God on our Arms I trust they will be) may probably be their last against the United States of America.

The battle did not go the way Rutledge had hoped. The British successfully laid siege to Charleston, taking control of the city in May. Rutledge eluded the British and escaped to North Carolina. From there, he operated a skeleton government. Though he escaped, he was not unscathed – all his property was seized, and he never regained his financial losses.

Nathanael Greene and his Continental Army force helped return Rutledge to South Carolina in 1781. In the succeeding years, he served in the lower house of South Carolina’s Congress (1782-1783) and on the South Carolina Court of Chancery (1784-1789). On a more national level, Rutledge attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787 as a representative of South Carolina. As a Federalist, he wanted a strong national government. He pushed for the President and federal judges to be elected by Congress. He also sought protection for the institution of slavery. He served on numerous committees and won the respect of his fellow delegates; William Pierce said that “he is undoubtedly a man of abilities, and a Gentleman of distinction and fortune.” In 1789, Rutledge became one of the first associate justices on the U.S. Supreme Court, holding his seat for two years.

In his final decade of life, Rutledge experienced difficulties and disappointments. His wife, Elizabeth (neé Grimké), died in 1792 after nearly thirty years of marriage and ten children. Losing her affected his mental wellbeing and overall health. Additionally, he experienced a public professional embarrassment when his nomination by President George Washington for Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court was denied. This outcome was likely a result of a speech he made opposing the Jay Treaty, which angered fellow Federalists. He attempted to drown himself soon after this event but was unsuccessful.

Rutledge died in Charleston, South Carolina, on July 18, 1800, at the age of sixty. He was buried in St. Michael’s Church Cemetery in Charleston.