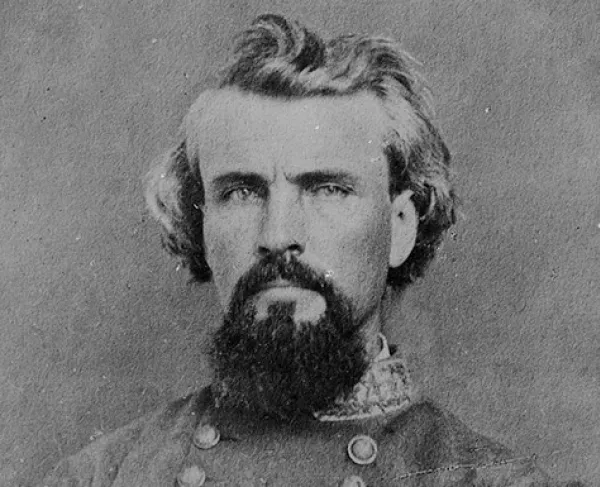

Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest, one of the most polarizing figures of the Civil War era, was born July 13, 1821 in Chapel Hill, Tennessee – a small town on the Duck River. When his father, a blacksmith, died when he was 16, Forrest moved to the Memphis Delta and eventually became a successful businessman – indeed a millionaire – dealing in cotton, land and slaves.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Forrest volunteered as a private before deciding to raise and equip an entire unit at his own expense. He was commissioned lieutenant colonel, and issued this call to arms in June, 1861:

“I wish none but those who desire to be actively engaged. COME ON BOYS, IF YOU WANT A HEAP OF FUN AND TO KILL SOME YANKEES”

In February 1862, Forrest’s unit was stationed at Fort Donelson on the Cumberland when Gen. Ulysses S. Grant forced its surrender. Rather than accept Gen. Buckner’s decision to capitulate, Forrest and his men slipped away, through the snow, and fought at the Battle of Shiloh less than two months later. That summer he began to make the kind of lightning raids that made him perhaps the single most feared cavalry commander of the entire war and earned him the nickname “the wizard of the saddle.”

He was promoted to brigadier general and at the close of the year made himself a thorn in the side of Grant’s Vicksburg campaign, disrupting his lines of communication and attacking his supply depots. During a skirmish at Parker’s Crossroads on New Year’s Eve, Forrest and his men were totally surprised when a Union force suddenly appeared in their rear and threatened to surround them. “Charge ‘em both ways,” Forrest famously ordered. They did, and were able to escape the trap and to fight another day. Constantly on the move, bold on the attack and swift in retreat, no Union commander was able to effectively come to grips with Forrest’s cavalry during the war. In September, they took part in the great battle of the Western Theater: Chickamauga. Forrest’s men pursued the retreating Union army into Chattanooga and took hundreds of prisoners. In December, 1863 he was again promoted to major general.

The following spring, in April 1864, Forrest and his men were involved in one of the most controversial episodes of the Civil War. After surrounding Fort Pillow, near Memphis, Forrest demanded the surrender of the garrison, which included 262 soldiers of the U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. When the Union forces refused, Forrest’s men easily overran the fort. Then, according to several eyewitness accounts, the Confederates, enraged by the sight of black men in Federal uniform, executed many of the colored troops after they had surrendered: an unambiguous war crime. Though accounts varied, the incident stands as one of the most gruesome of the Civil War era; “Remember Fort Pillow” became a rallying-cry for African-American soldiers throughout the Union Army.

Later in the summer, Forrest won one of his greatest victories at Brice’s Cross Roads, defeating a force twice the size of his own. His legend was constantly growing. That year, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman declared: “that devil Forrest must be hunted down and killed if it costs ten thousand lives and bankrupts the federal treasury.”

Forrest continued to torment the Union high command as the war entered its fourth year. In February, 1865 Forrest was again promoted, to lieutenant general, becoming the only man on either side to rise so far. When Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant in April, Forrest surrendered as well, declaring that, “any man who is in favor of a further prosecution of this war is a fit subject for a lunatic asylum.” Over the course of the conflict, Forrest had given as much as probably any man for the cause. He had 29 horses shot from under him, killed or seriously wounded at least thirty enemy soldiers in hand-to-hand combat, and had been himself wounded four times.

After the war, Forrest is best known as having been a prominent figure in the foundation of the Ku Klux Klan, a group composed of mostly Confederate veterans committed to violent intimidation of blacks, northerners and republicans. He was “Grand Wizard” until he ordered the dissolution of the organization in 1869. Forrest died of diabetes in Memphis on October 29, 1877.