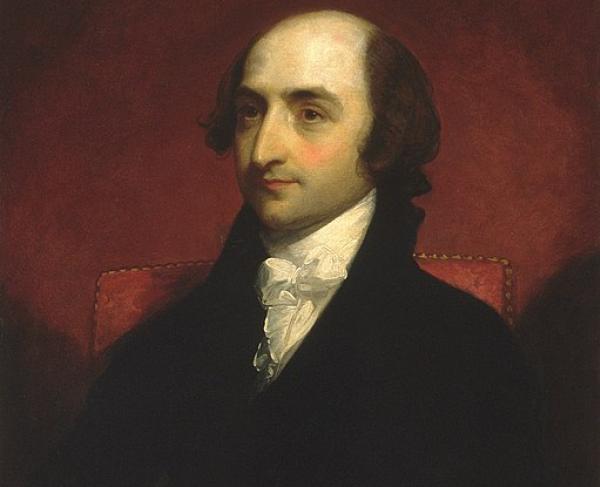

Emory Upton

Emory Upton was one of the most influential military thinkers to emerge from the Civil War. Born in Batavia, New York in 1839, Upton attended Oberlin College prior to accepting an appointment at West Point. While at the academy, Upton, an outspoken abolitionist, became involved in a fist fight when fellow cadet Wade Gibbs uttered a racial slur against him. In spite of this incident, Upton was an otherwise exemplary student and graduated eighth in the May class of 1861.

The newly commissioned Lieutenant Upton was assigned to the 5th Artillery Regiment in time to serve in the First Battle of Bull Run. During the battle he was wounded but refused to leave the field—the first of many such instances in Upton’s career. Upton commanded his battery during the Peninsula Campaign and was the head of an artillery brigade in the Sixth Corps during the Battle of Antietam.

In October of 1862, Upton received a promotion to colonel of the 121st New York Infantry. In this position he led the regiment through the battles of Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville—where his regiment received its baptism of fire—and Gettysburg, gaining notoriety and rising to brigade command along the way. However, Upton’s most significant contribution did not come until Grant’s Overland Campaign in May of 1864.

Facing the firmly entrenched Army of Northern Virginia, Upton petitioned his superiors to lead a brigade against the enemy’s fortifications. The young colonel believed that swiftly advancing in a narrow, compact formation without halting to fire would greatly enhance the assault’s probability of success. Though this approach was contrary to the tactics then in use, his superiors trusted his judgment. On May 10, 1864, Upton led a small force against the “Mule Shoe” salient (now the “Bloody Angle”) at Spotsylvania Court House. Though Upton’s charge lacked sufficient support to be decisive, the initial success of his new tactic inspired Ulysses S. Grant to implement if in an assault two days later—this time with General Winfield S. Hancock's entire corps. Similar tactics would later be used against trenches in the First World War. This bravery and ingenuity earned Upton a much-anticipated promotion to brigadier general.

After recovering from a wound received at Spotsylvania, General Upton returned to action in the initial phases of the siege of Petersburg and in the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. At the Third Battle of Winchester, Upton, then commanding a division in the Sixth Corps, was again wounded and again refused to relinquish command, choosing instead to direct his troops from a stretcher. The convalescing Upton was promoted to Major General and asked to participate in General James H. Wilson ’s cavalry raid through Alabama and Georgia. Accepting this offer, Upton became one of the few officers to effectively lead troops of all three branches of the army: artillery, infantry and, now, cavalry.

For the next fifteen years, Upton continued his military service as an instructor, most notably as the Commandant of West Point from 1870-1875. During this time he wrote A New System of Infantry Tactics, The Armies of Asia and Europe, and “The Military Policy of the United States from 1775.” These and other writings, drawn from his experiences in the Civil War—as well as his own personal observations of foreign military practices—advocated dramatic changes in the American Armed Forces including advanced military education and improved promotion protocols. Upton’s works were widely read in military circles and were later published by Secretary of War Elihu Root.

In the last years of his life, Emory Upton suffered from severe headaches, quite possibly migraines associated with a brain tumor. On March 15, 1881, while commanding the 4th Artillery in Presidio, California, he wrote out his resignation from the Army and promptly took his own life. Upton is buried in Fort Hill Cemetery, Auburn, New York