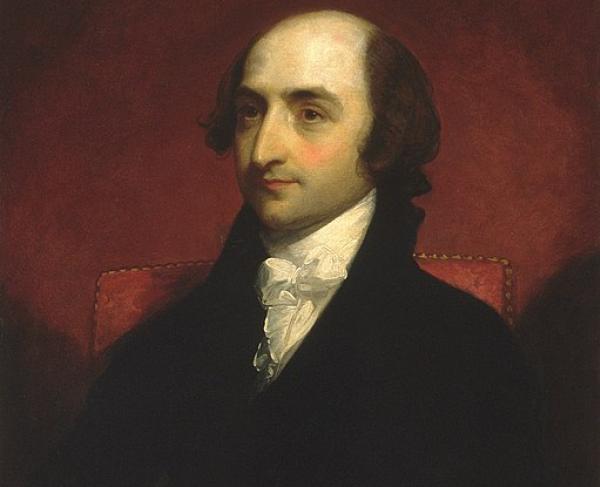

Edward Porter Alexander

Edward Porter Alexander was one of only three Confederate officers to rise to the rank of general in the artillery branch. Respected by some of the Confederacy’s most important commanders, Alexander would participate in nearly every major campaign in the eastern theatre, contributing substantially to the army’s greatest successes and sharing in its bitterest defeats.

Born in Washington, Georgia to Leopold and Sarah Gilbert Alexander, the future artillerist entered West Point during Robert E. Lee's tenure as the academy’s superintendent. Alexander graduated third of thirty-eight cadets in the class of 1857 and immediately accepted a commission as an engineer, a coveted position at that time. His early assignments included teaching at West Point, weapons experiments, and, most notably, devising a flag signal system for the U.S. Army—a system that would later be used by both Union and Confederate forces in the coming war.

In 1861, upon learning of his home state’s secession, Alexander resigned from the Federal army and accepted a commission as Captain of Confederate engineers. While organizing and training the new Confederate signal service, Alexander was ordered to report to General P.G.T. Beauregard and would serve as a signal officer in the First Battle of Manassas.

That fall, Alexander was transferred to the Army of Northern Virginia, the army with which he would be associated for the remainder of the war. He served as acting artillery chief under General Joseph E. Johnston and, in 1862, as chief of ordnance under Gen. Lee. Alexander would gain a solid reputation for his skill, bravery, and his keen eye for intelligence through the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days’ battles that followed. During the battle of Gaines’ Mill in June of 1862, Alexander ascended in a hot air balloon, providing Lee with vital information on General McClellan’s troop positions. Alexander would continue as chief of ordnance during the Second Battle of Manassas and the Battle of Antietam.

In November of 1862, Alexander was promoted to colonel and in December was given command of his own artillery battalion in General James Longstreet’s First Corps. At the Battle of Fredericksburg Alexander was responsible for placing the Confederate Artillery on Marye’s Heights. When asked by his superiors for an assessment of his dispositions, Alexander surmised that “a chicken could not live on that field when we open on it.” Alexander’s belief proved to be accurate, if not somewhat exaggerated. In what is considered by most to have been the most lop-sided Confederate victory of the entire Civil War, Alexander’s guns were instrumental in blunting the Federal assault.

By the summer of 1863, Alexander’s reputation in the Army of Northern Virginia was unquestioned and it is likely for this reason that the young colonel played such a pivotal role in the Battle of Gettysburg. Commanding the reserve artillery for Longstreet’s corps, Alexander’s guns lent support to Confederate assaults on July 2. The following day, July 3, Alexander was assigned to command the Confederate artillery barrage that was to clear the way for Pickett’s Charge. General Longstreet, whose doubts about the success of the charge would become legendary, placed upon Alexander the additional responsibility of telling Major General George Pickett when to commence the attack. When Federal fire had slackened, Alexander reluctantly sent word to Pickett. Unfortunately, Alexander’s barrage was less successful than hoped. After the initial surprise of the barrage, many Union guns conserved their ammunition for the infantry attack they knew was coming.

In spite of the defeat at Gettysburg, Alexander would continue to serve with distinction for the duration of the war, ultimately becoming First Corps chief of Artillery. In February of 1864 he was promoted to brigadier general and that spring saw action during Grant’s Overland Campaign. During the siege of Petersburg, General Alexander suspected that the Federals were tunneling underneath the Confederate lines, a suspicion that would later be confirmed. Before the plot could be foiled, however, Alexander was severely wounded by a Yankee sharpshooter. He returned from his wound in time to supervise the defense of Richmond and the retreat to Appomattox.

After the war, Alexander served briefly as a professor of engineering before moving onto other business ventures, including one in burgeoning railroad industry. Like many veterans, he wrote about his wartime experience and his memoir is considered one of the best contemporary analyses of the Army of Northern Virginia. Edward Porter Alexander died in Savannah, Georgia in 1910.