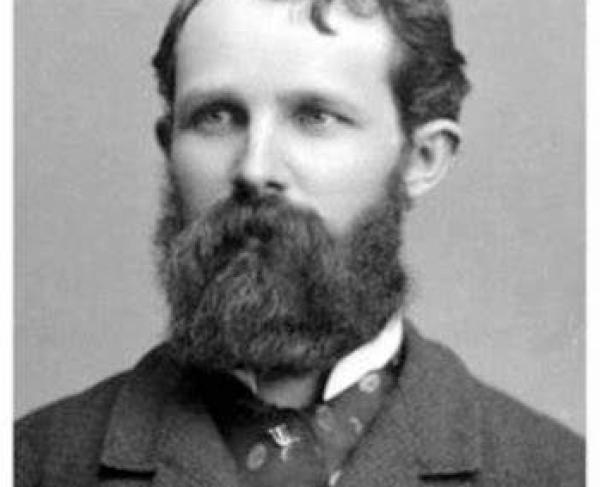

Henry Kyd Douglas

In 1861, as the war drums began their ominous beat, Shepherdstown, Va., resident and attorney Henry Kyd Douglas answered the call of the Old Dominion and enlisted — and in doing so assured himself a place in American history. Although he was born in Ireland on September 29, 1838, Douglas’s family emigrated in his childhood, eventually settling in western Maryland at Ferry Hill Place, immediately across the Potomac River from Shepherdstown.

After Virginia seceded, Douglas, along with many of his fellow citizens, cast his lot with the Confederacy and enlisted as a private in Company B of the 2nd Virginia Infantry. He would later write of that momentous event,

"When on the 17th of April, 1861, Virginia passed the Ordinance of Secession, I had no doubt of my duty. In a week I was back on the Potomac. When I found my mother sewing on heavy shirts – with a heart doubtless heavier than I knew – I suspected for what and whom they were being made. In a few days I was at Harpers Ferry, a private in the Shepherdstown Company, Company “B,” Second Virginia Infantry."

- Henry Kyd Douglas, I Rode with Stonewall, pg. 17.

Following the Battle of First Manassas, Douglas was promoted to second lieutenant and later accepted a position on General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s staff. He served in nearly every major campaign of the Eastern Theater — including Jackson’s famed 1862 Valley Campaign — and was wounded on no less than six separate occasions during the conflict.

Following the war, he made headlines when he flaunted his Confederate uniform in the streets of Shepherdstown, an act which Federal authorities deemed “a badge of treason and rebellion, intended and designed to encourage and incite rebellion.” Ultimately, this act of defiance landed him in a Washington, D.C., jail cell, and consequently led him to serve as a witness in the infamous trial of the Lincoln conspirators. Following his death in 1903, Douglas’s obituary in the New York Times recorded that no less than Varina Davis (widow of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis) once admitted, “With one exception, he was the handsomest man she had ever met.” Beyond his flair for the dramatic, Douglas was a consummate storyteller with a penchant for embellishment — his much heralded, colorful memoir, I Rode with Stonewall, was not published until many years after his death.

Today, a tangible link to his life and his incomparable memoirs remains at the Historic Shepherdstown Museum. The museum owns the field desk upon which he handled much of the correspondence while on Jackson’s staff — and where oral history holds that he wrote his first draft of I Rode With Stonewall, as the old desk helped conjure up his memories of the past. The well-worn desk, imbued with historic ink splatters and scrapes of ancient fountain pens, is a living testament to the life of this charismatic and engaging veteran.

- Nicholas Redding, Hallowed Ground Magazine, Spring 2012; Special Thanks to the Historic Shepherdstown Museum, historicshepherdstown.com