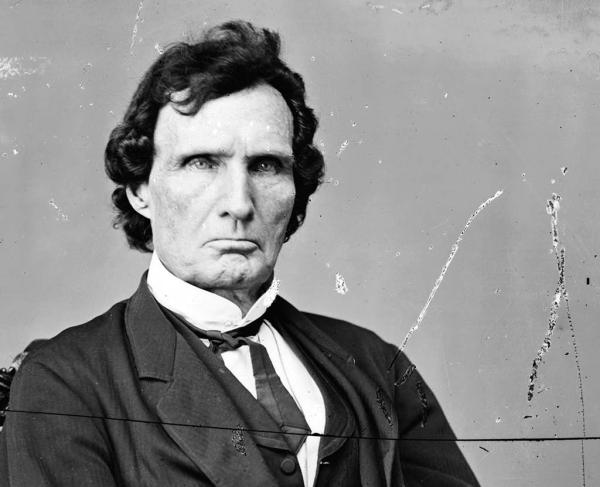

Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens was born on April 4, 1792, in rural Danville, Vermont, to Joshua and Sarah Stevens. He was moderately disabled by a club foot; this contributed to a difficult childhood worsened by his father’s abandonment of the family during Stevens’ adolescence. Sarah Stevens moved the family to Peacham, Vermont, and enrolled her four sons at the Caledonia Grammar School. After graduating from Caledonia, Stevens studied at Dartmouth College, where he excelled academically and was elected the commencement speaker in 1814. He worked as a teacher for two years while studying law, before establishing his own law practice in Gettysburg. Stevens was highly successful as a lawyer, demonstrating clear rhetoric and biting sarcasm, which would later make him an effective politician.

In 1822, Stevens entered politics and was elected to the first of six consecutive one-year terms as president of the Borough Council of Gettysburg. He became deeply involved in the Anti-Mason movement, which also placed him in opposition to the popular Jacksonian Democrats. He was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives on the Anti-Mason ticket in 1833. In the House, he advocated for public education and the rights of minorities, including Native Americans, Mormons, Seventh-Day Adventists, and Jews. In 1835, Stevens controversially subpoenaed leading state politicians and interrogated them about their Freemason affiliations; it cost him his seat in 1836.

Stevens remained involved in state politics and was a delegate to the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention in 1837. Stevens refused to sign the new constitution due to a clause restricting suffrage to “white freemen” which disenfranchised all Black Pennsylvanians. He became active in the abolitionist movement, working for full citizenship rights for Blacks and an end to the expansion of slavery. He did not yet support an immediate end to slavery in states where it existed, believing the federal government lacked the authority to interfere on a state level. This opinion would change with the outbreak of the Civil War. During this period, Stevens supported the Underground Railroad, defending escaped slaves in court and concealing them in his home.

In 1848, Stevens ran for Congress on the Whig ticket and claimed a seat representing Pennsylvania’s 8th congressional district in the House of Representatives. He opposed the Compromise of 1850 due to the inclusion of the Fugitive Slave Act, stating that “This word ‘compromise’ when applied to human rights and constitutional rights I abhor.” He left the Whig Party and, unpopular among his former fellow party members, did not run for re-election immediately. He returned to his law practice before briefly joining the nativist Know-Nothing Party for its anti-slavery platform. He left the next year, 1855, to join the newborn Republican Party. The party grew in prominence, and he easily won re-election to Congress in 1858.

During the Civil War, Stevens worked tirelessly and brilliantly to end slavery. In 1861, he facilitated the passage of an act allowing the federal government to confiscate certain property belonging to citizens supporting the rebellion, including slaves, making the measure an abolitionist one. He constantly pressured Abraham Lincoln to support full emancipation. In December 1863, Stevens assisted in drafting the Thirteenth Amendment, which would finally abolish slavery throughout the United States. When the amendment was held up in the House of Representatives due to Democratic opposition, Stevens participated in the debate and gave closing remarks soon before the amendment passed.

Stevens was also instrumental in financing Union efforts throughout the war. He assisted Lincoln’s administration by structuring a new emergency loan and crafting legislation that simplified war expenditures and paid volunteers efficiently. He helped pass the Legal Tender Act of 1862, which allowed the federal government to print money on its credit without a gold or silver standard. Stevens’s efforts to move these bills through the House quickly—such as cutting debate time on the bills to half a minute--earned him the nickname "Dictator."

Stevens remained in Congress for the remainder of his life, always aligned with the “Radical Republican” wing of his party. During the early years of Reconstruction, he harshly criticized the Southern states, arguing that they deserved to be treated as a conquered nation that the United States could restructure as it saw fit. He strongly opposed President Andrew Johnson’s administration, not only for what he saw as a soft stance on the South but also for its lack of support for freedmen’s rights. He was a key figure in the impeachment trial of Johnson and was deeply disappointed by Johnson’s acquittal. In his final years, he saw the wane of Radical Republican influence but declared himself still committed to the cause and especially to protecting Blacks from violence in the South. Too ill to return to Pennsylvania when Congress adjourned in July 1868, Stevens died just weeks later in Washington at age 76. Thousands viewed his casket or attended his funeral before he was buried in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.