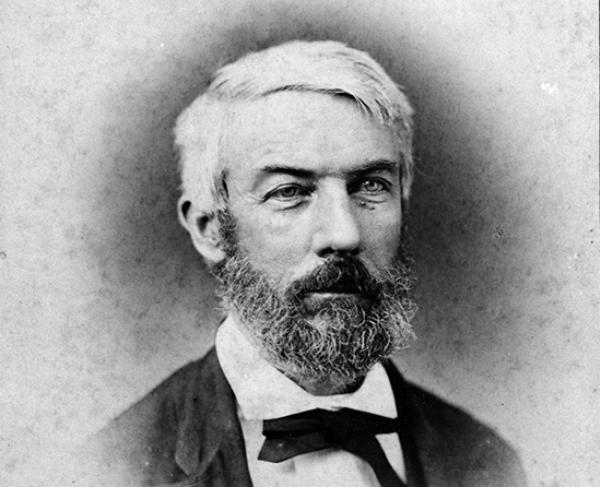

Daniel Harvey Hill

Daniel Harvey Hill was born on July 12, 1821, in what is now York County, South Carolina. He entered West Point in 1838 and graduated in 1842, finishing 28th in his class of 56. Among his classmates were several future Civil War generals, including William S. Rosecrans, Abner Doubleday, Earl Van Dorn, and James Longstreet. After his graduation he was assigned to the 1st US Artillery.

In the Mexican War, Hill was brevetted twice, first for bravery at the Battles of Contreras and Churubusco, then for bravery at the Battle of Chapultepec. He also fought at Vera Cruz and Cerro Gordo. In 1849 he resigned his commission and became a professor of mathematics at Washington College (now Washington and Lee University). In 1854 he joined the faculty of Davidson College in North Carolina and in 1859 he became the superintendent of the North Carolina Military Institute.

While teaching mathematics, Hill wrote an algebra textbook, entitled Elements of Algebra, which included numerous questions denigrating the North. One question, for example, asked: At the Women’s Rights Convention, held at Syracuse, New York, composed of 150 delegates, the old maids, childless-wives, and bedlamites were to each other as the numbers 5, 7, and 3. How many were there in each class?”

In 1848, Hill married Isabella Morrison, with whom he would have nine children. In 1857, Hill’s sister-in-law, Mary Anna Morrison, married Thomas J. Jackson, a teacher at the Virginia Military Institute who would later earn fame in the Civil War. That same year, Jackson wrote a testimonial for Hill’s textbook, describing it as “superior to any other work with which I am acquainted on the same branch of science.”

When the Civil War began, Hill was appointed to the colonelcy of the 1st North Carolina Infantry. He quickly achieved success, leading Confederate forces to victory at the Battle of Big Bethel in Virginia on June 10, 1861. By the spring of 1862, Hill was a major general in command of a division in the Army of Northern Virginia. He led his troops at Yorktown, Williamsburg, Seven Pines, and throughout Robert E. Lee’s Seven Days Campaign. At Malvern Hill, he unsuccessfully urged Lee not to attack what would prove to be an impregnable Federal position.

During the Northern Virginia Campaign, Hill was left behind to defend Richmond. During this time he developed a system for prisoner of war exchanges with Union General John A. Dix. He rejoined Lee’s army later that summer when Southern forces moved into Maryland.

During the Maryland campaign, Hill was mistakenly sent two copies of Special Orders No. 191, which detailed the divided positions of Confederate forces. One was left in a field near Frederick, Maryland, where a Union soldier discovered what would become known as Lee’s “Lost Order.”

Realizing that Lee’s divided army was vulnerable, Union General George McClellan pursued the Confederates with uncharacteristic speed. On September 14, Hill was ordered to slow the Union advance at a gap in South Mountain. For an entire day, Hill’s outnumbered men held out, buying precious time for Lee’s army. Three days later, at Antietam, Hill’s division defended the “Bloody Lane” against repeated Union assaults before being driven back. Hill's division also participated in the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Although Hill was widely recognized as a superb combat leader, he had a tendency to make enemies. One Confederate official described Hill as “harsh, abrupt, often insulting in the effort to be sarcastic.” According to James Longstreet, Hill’s cause was furthermore undermined by the fact that he was a North Carolinian in an army of Virginians.

In the spring of 1863, Hill was detached to help defend North Carolina and Southern Virginia. He never rejoined Lee’s army. After helping defend Richmond during Lee’s Gettysburg Campaign, Hill was sent west to command a corps in Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Hill led his corps in the victory at the Battle of Chickamauga. After the battle, however, tensions with Bragg led to Hill being sidelined and to the cancellation of his promotion to lieutenant general. Hill did not command troops in a significant engagement again until the Battle of Bentonville in the final weeks of the war.

After the war, Hill founded a magazine entitled The Land We Love, which included coverage of literature, history, and agriculture. He edited the journal from 1866 to 1869. From 1877 to 1884 Hill served as the first president of the University of Arkansas. In 1885 he became president of the Military and Agricultural College of Milledgeville in Georgia. He held the post until August 1889, when, due to failing health, he resigned and returned to Charlotte, North Carolina, where he died on September 24, 1889. Hill is buried in the Davidson College Cemetery.