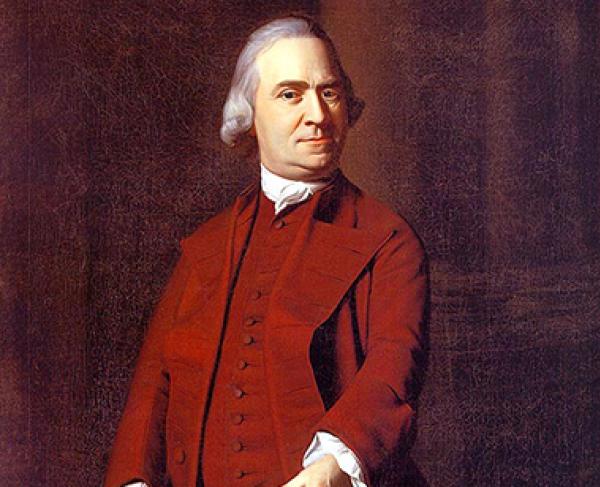

Samuel Adams

Born as the son of a church deacon in 1722, Samuel Adams understood from a young age the authority private citizens could hold over politics once properly mobilized. Adams acquired something of a historical reputation—in his own time no less—as a rabble-rouser and propagandist for the independence movement, especially in comparison to his second cousin John, the future president. But those accusations tend to obscure his nature as an astute political thinker and a tireless activist. Adams' father, also named Samuel, frequently used his position as preacher to organize large numbers of associates into groups to lobby local Boston politicians and officials on specific issues, with young Sam frequently accompanying him. At the age of fourteen, Adams entered Harvard, ostensibly to study theology and later take up his father's career, but life in college also exposed him to the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers like John Locke, who held that certain rights and liberties were inherent to humanity, and that government should reflect that truth.

Upon graduation, Adams tried his hand at various businesses, from accounting to joining his father's brewing company, but he always drifted close to the political sphere. He took up a public writing career very early on as a public writer, similar to that of a modern political pundit or Op-Ed writer. He and a circle of close friends launched their first publication, The Public Advertiser. Through the Advertiser, Adams warned his fellow Bostonians to be wary of both calls to submission as well as revolution, and to cherish liberty and the laws that grant it above all.

Adams got the chance to put those words into action after the Seven Years War, when Britain decided that the American colonies needed to pay more of a share to help pay for a war the colonists essentially began. Starting in 1764, the British Parliament began levying several taxes on the colonies to rectify the situation, starting with the American Revenue Act or Sugar Act, essentially a tariff on imported sugar. Most colonists grumbled about London harming the North American economy to the benefit of the sugar-producing colonies in the West Indies, but Adams raised broader political concerns, arguing that London had violated the colonist's rights as Englishmen. "The most essential rights of British Subjects," he wrote, "are those of being represented in the same Body which exercises the Power of levying Taxes upon them." He also began reaching out to New England merchants affected by the new law and convinced them to begin boycotting all goods connected with the tax. When Parliament replaced the Sugar Act with the notoriously unpopular Stamp Act, Adams called out even louder in protest. As further Acts of Parliament, one of which placed Boston under military occupation, further enraged the colonies, Samuel Adams could be found at the center of the protests, not necessarily threatening revolution and independence, but warning Britain about the possibility. Many have noted Adams' role in promoting news about the Boston Massacre across the Thirteen Colonies, but in fairness, he highlighted the need for the accused soldiers to receive a fair trial, convincing his cousin John to take up their defense. Though Adams generally believed that reasoned words carried more political weight than aggressive actions, not every disgruntled colonist held this opinion, as tarring and feathering became a common form of violent protest against British customs officials.

Adams' real first foray of active resistance came in 1773, when Parliament passed the Tea Act, requiring that, combined with the previous Townshend Acts, effectively forced the colonists to buy tea from one source, the British East India Company. In response, an enormous group of disgruntled townsfolk gathered in Boston's Old South Meeting House, where Adams began organizing vigilante groups charged with preventing the tea shipments from ever reaching the docks. According to him in a letter to one Arthur Lee, these meetings were "conducted with decency, unanimity, and spirit." One of these groups, about 100 strong, decided to take even further action by dressing up as Mohawk warriors, sneaking aboard the ships and then dumping the tea into Boston Harbor, an act which became the famous Boston Tea Party. Similar events also occurred in Philadelphia and Annapolis. It is difficult to assess if Adams was personally involved in the protest, but he certainly celebrated it immediately afterwards, writing, "Our Enemies must acknowledge that these people have acted upon pure and upright Principle."

As tensions between Britain and the colonies spilled over into armed rebellion, Adams remained on the forefront of political affairs. As a delegate to the Continental Congress, Adams acted as both a signer of the Declaration of Independence as well as a framer of the Articles of Confederation, the governing laws of America before the Constitution. After the war, Adams went home to Boston and again flirted between business, writing and politics as a career. After serving as Lieutenant, then Acting Governor for John Hancock, Adams was elected 4th Governor of Massachusetts in 1794. Though elected for four years, he decided to retire early in '97 on account of his health, which also caused the end of his writing career. Samuel Adams passed away in 1803 and remains to this day in the Granary Burying Ground in Boston.