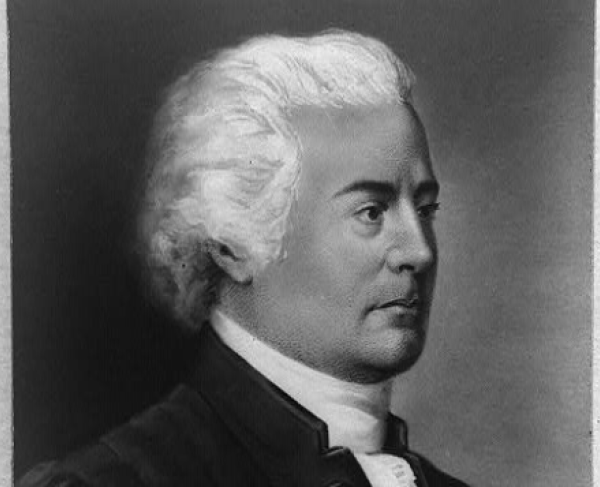

William Alexander, Lord Stirling

Though not always the most recognizable person in the Revolutionary War, William Alexander, "the Lord Stirling," was certainly a colorful figure nonetheless. Born in New York sometime in the year 1727, his father, James, served as an engineer for the Jacobite rebels in 1715 and so was promptly exiled from Scotland. His mother, Mary, was a successful New York businesswoman, and together the pair passed a strong interest in mathematics to their son. William grew up well-educated with a large inheritance, and made plenty of his own money by partnering with his mother in business as well, but he sought the proper prestige to go along with his life of luxury. In 1759, he made an attempt to cement his position by making a claim to the disputed Earldom of Stirling, not to mention a large territorial claim in Nova Scotia that went along with it. Though William proved his relation to the original earls and was generally accepted by the Scottish Peerage, and though a Scottish court granted him the title, he was blocked by the House of Lords due to the differing laws of succession between Scotland and England. Not one to be dejected, however, William continued to refer to himself as "the Lord Stirling," living a lifestyle fit for any proper nobleman.

Despite his pretentions to aristocracy, Stirling was a firm supporter of the patriot cause by 1776 and received a commission as colonel for the New Jersey militia. The earl had previous military experience as an aide-de-camp to General William Shirley during the French and Indian War, but was chosen mostly for his political influence and local popularity. This paid off, though, as Stirling frequently had his troops trained and equipped at his own expense. Furthermore, Stirling proved a brave and able commander on multiple counts throughout the war, and was frequently promoted as a result.

His first definite moment of fame came at the Battle of Long Island. The battle was one of the worst defeats America suffered during the entire revolution, but Stirling, in command of the 1st Maryland regiment, proved his mettle by ordering repeated charges against the British lines while the rest of the army retreated. The action was costly; over half of the 400 Marylanders from the unit were killed in action, and Stirling himself was taken prisoner by the British, but their courage allowed the rest of the army to escape annihilation.

Stirling soon returned to Washington's service after a prisoner exchange, and took part in both the Crossing the Delaware and the Battle of Princeton, leading to his promotion to Major General in the February of 1777. He later served in the battles of Brandywine and Germantown during Sir William Howe's invasion of Pennsylvania, and also helped expose the "Conway Cabal," a conspiracy of certain Continental officers to have George Washington removed as Commander-in-Chief. Later, as the focus of the war moved south, Stirling remained in New York to protect the colonies against further raiding.

Unfortunately, Stirling's lifestyle of excessive eating and drinking eventually caught up with him, and he died of gout in 1783, just a few months before the war ended. He was buried in the Trinity Churchyard in Manhattan. Many of his descendants and relatives also filled important roles in the early years of the United States, including his great-great grandson Philip "the Magnificent" Kearny, who died in the Battle of Chantilly during the Civil War.